Abstract

Do committee speeches predict campaign contributions or vice versa? I study the dynamic endogenous interactions of energy sector campaign contributions to members of the U.S. Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources and their reactions in the 105th–112th Congresses. Utilizing a Bayesian Structural VAR approach, I find evidence for a dynamic model where the interactions between rhetoric and contributions are bidirectional—donors and senators are sensitive to changes in each others’ signaling and their responses follow immediately. The analysis shows that lags, leads, and contemporaneous effects in the exchanges are not mutually exclusive. The signaling of both sets of political actors is sensitive to external pressures and these effects differ depending on their party’s position of power. The contributions drive most of the variation in the rhetoric, and Democrats and Republicans follow similar strategies dependent on their position of power.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Chosen following lag length evaluation and in accordance with Brandt and Williams (2006, 25), who note that models with up to 8 to 10 lags will capture most of the expected seasonality.

References

Ainsworth, S.H. 1997. The role of legislators in the determination of interest group influence. Legislative Studies Quarterly 22 (4): 517–533.

Austen-Smith, D. 1992. Strategic models of talk in political decision making. International Political Science Review 13 (1): 45–58.

Austen-Smith, D. 1995. Campaign contributions and access. American Political Science Review 89 (3): 566–581.

Austen-Smith, D. 1998. Allocating access for information and contributions. Journal of Law, Economics and Organization 14 (2): 277–303.

Baron, D.P. 1989. Service-induced campaign contributions and the electoral equilibrium. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 104 (1): 45.

Bauer, R.A., Id.S. Pool, and L.A. Dexter. 1963. American business and public policy. The International Executive 5 (3): 25–27.

Baumgartner, F.R., J.M. Berry, M. Hojnacki, B.L. Leech, and D.C. Kimball. 2009. Lobbying and policy change: Who wins, who loses, and why. University of Chicago Press.

Brandt, P.T., M. Colaresi, and J.R. Freeman. 2008. The dynamics of reciprocity, accountability, and credibility. Journal of Conflict Resolution 52 (3): 343–374.

Brandt, P.T., and J.R. Freeman. 2006. Advances in bayesian time series modeling and the study of politics: Theory testing, forecasting, and policy analysis. Political Analysis 14 (1): 1–36.

Brandt, P.T., and J.R. Freeman. 2009. Modeling macro-political dynamics. Political Analysis 17 (2): 113–142.

Brandt, P.T., and J.T. Williams. 2006. Multiple time series models, vol. 148. Incorporated: Sage Publications.

Brunell, T.L. 2005. The relationship between political parties and interest groups: Explaining patterns of pac contributions to candidates for congress. Political Research Quarterly 58 (4): 681–688.

Burstein, P., and A. Linton. 2002. The impact of political parties, interest groups, and social movement organizations on public policy: Some recent evidence and theoretical concerns. Social Forces 81 (2): 380–408.

Cooley, T.F., and S.F. LeRoy. 1985. Atheoretical macroeconometrics: A critique. Journal of Monetary Economics 16 (3): 283–308.

Coughlin, P.J., D.C. Mueller, and P. Murrell. 1990. Electoral politics, interest groups, and the size of government. Economic Inquiry 28 (4): 682–705.

Deering, C.J., and S.S. Smith. 1997. Committees in Congress. SAGE Publications.

Denzau, A.T., and M.C. Munger. 1986. Legislators and interest groups: How unorganized interests get represented. American Political Science Review 80 (01): 89–106.

Diermeier, D., J.-F. Godbout, B. Yu, and S. Kaufmann. 2012. Language and ideology in congress. British Journal of Political Science 42: 31–55.

Drew, E. 2000. The Corruption of American Politics: What went wrong and why. Overlook Press.

Edwards, G.C., and B.D. Wood. 1999. Who influences whom? the president, congress, and the media. American Political Science Review 93 (02): 327–344.

EIA (U.S. Energy Information Administration) (2011). Annual energy review. Web. URL: http://www.eia.gov. Accessed: 2014-03-16.

Filler, D.M. 2002. Making the case for megan’s law: A study in legislative rhetoric. Indiana Law Journal 76 (2): 315–365.

Freeman, J. R., J. T. Williams, and T. min Lin. 1989. Vector autoregression and the study of politics. American Journal of Political Science 33 (4): 842–877.

Gerrish, S. and D.M. Blei. 2011. Predicting legislative roll calls from text. In Proceedings of the 28th international conference on machine learning (icml-11), pages 489–496.

Gerrish, S., and D.M. Blei. 2012. How they vote: Issue-adjusted models of legislative behavior. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 25: 2753–2761.

Goldstein, J.S., and J.R. Freeman. 1991. Us-soviet-chinese relations: Routine, reciprocity, or rational expectations? American Political Science Review 85 (01): 17–35.

Hall, R.L., and A.V. Deardorff. 2006. Lobbying as legislative subsidy. American Political Science Review 100 (01): 69–84.

Hall, R.L., and F.W. Wayman. 1990. Buying time: Moneyed interests and the mobilization of bias in congressional committees. American political science review 84 (03): 797–820.

Hayes, M.T. 1981. Lobbyists and legislators: A theory of political markets. Rutgers University Press.

Hojnacki, M., and D.C. Kimball. 1998. Organized interests and the decision of whom to lobby in congress. American Political Science Review 92 (04): 775–790.

Hopkins, D.J., and G. King. 2010. A method of automated nonparametric content analysis for social science. American Journal of Political Science 54 (1): 229–247.

Iaryczower, M., G.L. Moctezuma, and A. Meirowitz. 2018. Career concerns and the dynamics of electoral accountability. https://dropbox.com/s/4pn131nw2prnfbm/careerdynamics_may20_post.pdf.

Iliev, I.R., and P.T. Brandt. 2020. Money and rhetoric: Energy sector dynamics in u.s. senate committee. The Social Science Journal. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soscij.2019.05.005.

Iliev, I.R., X. Huang, and Y.R. Gel. 2019. Political rhetoric through the lens of non-parametric statistics: Are our legislators that different? Journal of the Royal Statistical Society 182: 583–604. https://doi.org/10.1111/rssa.12421.

Iliev, I.R., X. Huang, and Y.R. Gel. 2020. Speaking out or speaking in? changes in political rhetoric over time. Significance 17 (5): 22–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/1740-9713.01445.

Jacobson, G.C. 1985. Party organization and distribution of campaign resources: Republicans and democrats in 1982. Political Science Quarterly 100 (4): 603–625.

Kass, R.E., and A.E. Raftery. 1995. Bayes factors. Journal of the american statistical association 90 (430): 773–795.

Laver, M., K. Benoit, and J. Garry. 2003. Extracting policy positions from political texts using words as data. American Political Science Review 97 (2): 311–331.

Lowery, D., and H. Brasher. 2004. Organized interests and American government. McGraw-Hill.

Lowery, D., V. Gray, M. Fellowes, and J. Anderson. 2004. Living in the moment: Lags, leads, and the link between legislative agendas and interest advocacy*. Social Science Quarterly 85 (2): 463–477.

Mayhew, D.R. 2004. Congress: The electoral connection, vol. 26. Yale University Press.

McCarty, N., and L. Rothenberg. 1996. Commitment and the campaign contribution contract. American Journal of Political Science 40 (3): 872–904. https://doi.org/10.2307/2111799.

McChesney, F.S. 1997. Money for nothing: politicians, rent extraction, and political extortion. Harvard University Press.

Mitchell, W.C., and M.C. Munger. 1991. Economic models of interest groups: An introductory survey. American Journal of Political Science 35 (2): 512–546.

Nowlin, M. 2016. Modeling issue definitions using quantitative text analysis. Policy Studies Journal 44 (3): 309–331.

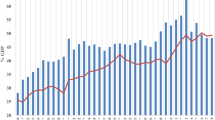

OpenSecrets.org 2013. Energy/natural resources: Long-term contribution trends. Web. http://www.opensecrets.org/industries/totals.php?cycle=2012&ind=E. Accessed: 2014-03-16.

Potoski, M., and J. Talbert. 2000. The dimensional structure of policy outputs: distributive policy and roll call voting. Political Research Quarterly 53 (4): 695–710.

Romer, T., and J.M. Snyder. 1994. An empirical investigation of the dynamics of pac contributions. American Journal of Political Science 38 (3): 745–769.

Sattler, T., J.R. Freeman, and P.T. Brandt. 2008. Political accountability and the room to maneuver: A search for a causal chain. Comparative political studies 41 (9): 1212–1239.

Schickler, E. 2001. Disjointed pluralism: Institutional innovation and the development of the US Congress. Princeton University Press.

Schlozman, K.L. 1984. What accent the heavenly chorus? political equality and the american pressure system. The Journal of Politics 46 (04): 1006–1032.

Sinclair, B. 2016. Unorthodox lawmaking: New legislative processes in the US Congress. CQ Press.

Snyder, J.M. 1989. Election goals and the allocation of campaign resources. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society 57 (3): 637–660.

Snyder, J.M. 1990. Campaign contributions as investments: The us house of representatives, 1980–1986. Journal of Political Economy, pp. 1195–1227.

Stramp, N., and J. Wilkerson. 2015. Legislative explorer: data-driven discovery of lawmaking. PS: Political Science & Politics 48 (01): 115–119.

Stratmann, T. 1995. Campaign contributions and congressional voting: does the timing of contributions matter? The Review of Economics and Statistics 77 (1): 127–136.

Stratmann, T. 1998. The market for congressional votes: Is timing of contributions everything? The Journal of Law and Economics 41 (1): 85–114.

Talbert, J.C., B.D. Jones, and F.R. Baumgartner. 1995. Nonlegislative hearings and policy change in congress. American Journal of Political Science 39 (2): 383–405.

Truman, D.B. 1971. The governmental process. Alfred A. Knopf New York

Wand, J. 2007. The allocation of campaign contributions by interest groups and the rise of elite polarization. Manuscript: Stanford University.

Wand, J. and W.R. Mebane, 1999. Learning in campaigns: A policy moderating model of individual contributions to house candidates. In Annual Meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association, April, pages 15–17.

Welch, W.P. 1974. The economics of campaign funds. Public Choice 20 (1): 83–97.

Wright, J.R. 1990. Contributions, lobbying, and committee voting in the us house of representatives. The American Political Science Review 84 (2): 417–438.

Yano, T., N.A. Smith, and J.D. Wilkerson, 2012. Textual predictors of bill survival in congressional committees. In Proceedings of the 2012 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, pages 793–802.

Yu, B., S. Kaufmann, and D. Diermeier. 2008. Classifying party affiliation from political speech. Journal of Information Technology & Politics 5 (1): 33–48.

Zeigler, L.H., and G.W. Peak. 1964. Interest groups in American society, vol. 343. NJ: Prentice-Hall Englewood Cliffs.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Iliev, I.R. The power dynamics of campaign contributions and legislative rhetoric. Int Groups Adv 10, 240–263 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41309-021-00125-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41309-021-00125-0