Abstract

This article presents research notes on an oral history project on the impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on Jews over the age of 65 years. During the first stage of the project, we conducted nearly 80 interviews in eight cities worldwide: Amsterdam, Berlin, London, Milan, New York, Paris, Rio de Janeiro, and St. Petersburg, and in Israel. The interviews were conducted in the spring of 2020 and reflect the atmosphere and perception of interviewees at the end of the first lockdown.

Based on an analysis of the interviews, the findings are divided into three spheres: (1) the personal experience during the pandemic, including personal difficulties and the impact of the lockdown on family and social contacts; (2) Jewish communal life, manifested in changed functions and emergence of new needs, as well as religious rituals during the pandemic; and (3) perceived relations between the Jewish community and wider society, including relations with state authorities and civil society, attitudes of and towards official media, and the possible impact of COVID-19 on antisemitism. Together, these spheres shed light on how elderly Jews experience their current situation under COVID-19—as individuals and as part of a community.

COVID-19 taught interviewees to reappraise what was important to them. They felt their family relations became stronger under the pandemic, and that their Jewish community was more meaningful than they had thought. They understood that online communication will continue to be present in all three spheres, but concluded that human contact cannot be substituted by technical devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

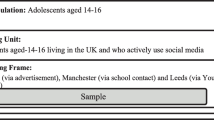

In the following pages, we will present our research notes of an oral history project conducted by the Oral History Division of the Avraham Harman Research Institute of Contemporary Jewry, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, together with the Israel Oral History Association.Footnote 1 These interviews are analyzed as personal narrative that attempt to capture the zeitgeist of the early stage of COVID-19 through interviews that reflect the complex situation of persons aged 65+ years in different countries. These research notes use as raw material the 80 interviews conducted in nine Jewish communities in Europe and the Americas and present the major subjects that arose from the interviews. One of our objectives is to expose scholars to this corpus of oral histories and to enhance its use for further studies.Footnote 2

During the early stages of the pandemic, public attention was directed to the population at risk, namely the elderly whose vulnerability, solitude, and difficulties dominated the media and the public sphere. Jewish communities were confronted by new challenges and needs, especially with respect to older persons who comprise a growing sector in most Western communities. For this reason, we chose this age group as the target population for our project.

The 80 interviews conducted during the first stage of the project took place in the following cities: Amsterdam, Berlin, London, Milan, New York, Paris, Rio de Janeiro, and St. Petersburg, and in Israel (Bnei Brak, Jerusalem and Tel Aviv). Interviewees were located at random, and do not pretend to be a representative sample. Nevertheless, they offered perceptions on personal lives and on social solidarity in their Jewish and wider communities. The interviews were conducted during the first phase of the health crisis, particularly in May–June 2020, when most of the respondents were isolated in their homes for several months and were expecting a gradual loosening of the lockdown. This article reflects the atmosphere of that period.

Most participants were over 65 years. Five younger interviewees were selected given their engagement in social work with the elderly people or their significant community roles.Footnote 3 Since the interviews were conducted remotely, we were limited to interviewees with access to technology. Indeed, most of them were middle or upper-middle class, with many being professionals. These oral histories tap the zeitgeist, shedding light on the difficulties and anxieties, as well as the empowerment of the senior members of Jewish communities. Oral history is a particularly appropriate approach to documenting changes during the present time, and creating this corpus of interviews may help Jewish communities worldwide understand, narrate, and create personal and collective memories of the first phase of the pandemic (Kelly 2020).

This article presents the project’s notes, using an analytical approach of oral history. Based on the analysis of narratives, as they appear in the interviews, it is divided into three topics: (1) the personal experience during the pandemic; (2) Jewish communal life as reflected in the interviews; and (3) perceived relations between the Jewish community and wider society. Together, these topics shed light on how elderly Jews experience their current situation under COVID-19—as individuals and as part of a community.

“Being Close without being Close:” Some Methodological Observations

M.K. Rio de Janeiro.

Oral history theories deal with the dynamics of remembrance that tend to change memories under different circumstances, and thus may be analyzed in different ways (Passerini 1998, 54, Portelli 1998, 69). Oral historians point out different layers of significance that can be attributed to personal narratives as the key to understanding historical experience, as well as oral histories as transmitters of social or political messages, as reflections of culture, or as political weapons of marginal and oppressed groups (Abrams 2010, Portelli 2003, Perks and Thomson 2015). While in most oral history studies interviewees look back to their past experiences, our project aims to grasp the insight of the interviewees toward their specific situation of the lockdown during the world pandemic—an experience that they share with the interviewers. In this unique situation of similar circumstances in different contexts, we offer scholars a collection of personal narratives as primary sources for comparative studies.

Interviews are generally conducted between two persons sitting in the same room and having an intimate conversation, while the interviewer is exposed not only to the narrative but also to the private space of the interviewee and can read his or her body language. While we are aware that face-to-face interviews are irreplaceable, under the constraints of COVID-19 we were forced to rely on online communication.

Our team comprised interviewers speaking Dutch, English, French, German, Hebrew, Italian, Spanish, and Russian.Footnote 5 Interviewees were selected through personal connections with individuals and community leaders in the different cities under study, as well as with the snowball method, using the recommendations of former interviewees. Interviewees were informed that the aim of the project is to record the impressions of those who are coping with the COVID-19 pandemic. Interviewers were given a list of more than 50 questions but were instructed not to stick to the questionnaire, but to conduct an open conversation, and to adapt the questions to each individual interviewee. In addition to questions on the impact of COVID-19 on their lives and on the maintenance of Jewish lifestyle, they were asked about their involvement in Jewish communal life and in the civil society of their respective countries, as well as about their perceptions and expectations. Interviewees had to sign a release, or to confirm orally their consent to the use of the interview for research, and to the citation of their names in future publications. Only a few interviewees requested that their interview be anonymous.Footnote 6

Zoom represented a new opportunity to overcome geographical distances at no expense and to interview during lockdown without having to risk the health of the interviewees or the interviewers. Remote interviewing is unavoidable given COVID-19, but it is not recommended for other projects, such as recording life stories for long-term preservation. Note that during online interviews it is difficult to create the intimate atmosphere that helps interviewees delve into their hidden memories, and that the visual quality of Zoom or other applications is below that of high-quality cameras. It helps, however, in confronting and elaborating on one's experiences during the pandemic. In addition, though not intentionally, the visual contact had a positive impact on the interviewees, even without a face-to-face meeting.Footnote 7

Remote video contact was not only relevant for the interviewees, but also for some of the interviewers, who found in the project an anchor of stability in a period of uncertainty. The Zoom interview was an external interference in the secluded routine of most interviewees. It was an opportunity—especially for women—to dress up, make up, wear jewelry, or put on a scarf. After long weeks of lockdown, these simple daily gestures should not be taken lightly. Getting ready for the interview was a preparation for a new self-appraisal in a time in which one’s visibility was limited for both interviewers and interviewees (Korichi, Pelle-de-Queral, Gazano and Aubert, 2008).

At the same time, the online interviews presented new challenges.Footnote 8 The low resolution of the video recording often caused loss of information, such as the concealment of blurred facial expressions, and it was sometimes difficult to understand the subtleties of sarcasm or cynicism. In addition, interviewees were viewed from their shoulders up, their hands invisible, making it difficult for the interviewer to read their entire body language. The limited nonverbal communication could affect the duration of the interview, since the interviewer was not aware of body movements conveying discomfort or fatigue.

Other disadvantages of Zoom had to do with technical problems. Interviewees were not always familiar with the technology and relied on family members to help them during the interview. Moreover, there was a slight delay between the question and response, and sometimes the interviewer had to repeat the question several times, and the interviewee had to answer a question more than once, because of image freezing or voice distortion. Interviews were conducted in the format of a shared screen, so that both parties were seen side by side and could keep eye contact. At the same time, their constant presence on the screen made them conscious of their own appearance throughout the interview, distracting their attention from the conversation.

“I don't want to die but this ain't Living Either:” The Personal Experience

D. S., London.

The first reports of a new virus reached the interviewees around the turn of 2020, but most of them thought that, like other viruses during the last decades, such as the swine flu, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), or Ebola, it would not affect their lives. Only when COVID-19 arrived at their threshold did this perception change. The interviews reflect the process in which awareness of the pandemic penetrated the participants’ minds. On Purim Eve (March 9–10), Jews went to the synagogues to read the Megillah (Book of Esther), unaware of the risks of gathering together. G.E. from Paris recalls that by that time one of the persons present in his synagogue was already infected, but that none of the others wore masks, and only a week later, following the official declaration on the pandemic, did they start taking precautions. R.L. attended a meeting in Beit Chabad in Rio de Janeiro shortly after returning from New York. He expressed his fears when he saw that a Kiddush (blessing) was taking place in a small room full of people who were not wearing masks. The two rabbis present assured him that God was protecting the Jews, and that mitzvah messengers—those who fulfill the commandments—are safe from harm (R.L. & L.L., July 2020).

The emergency situation caused by COVID-19 was gradually internalized. In Israel, this happened with the arrival of the passengers of the Diamond Princess.Footnote 10 In Brazil, the carnival was a hotbed for spreading the virus internationally. Most of the Brazilian interviewees said that they did not wait for government instructions, but decided to take preventive measures following information obtained from the internet or their private doctor. Like in Europe and Israel, they started to store food, toilet paper, masks, and gloves, and to maintain social distance. They shopped online, worked from home, and continued to pay their housekeepers’ salaries, asking them to remain in their homes (D.A.G., E.P., H.V., S.G., M.K., May–June, 2020).

The few interviewees caught in their holiday houses when the pandemic broke out could benefit from being far from contagion centers. The children of A.K and J.P.K. urged them to move to their mountain home where they could go out safely and be far from possible riots in Paris (A.K., L.W.R., M.D.P., May–June 2020). Most interviewees, however, were confined to their city dwellings and became dependent on food and medicines delivered by online suppliers, or by relatives or volunteers.

Being segregated from the public space and confined to one's home created a new situation.Footnote 11 Unable to meet relatives and friends increased the feeling of aloneness, especially for interviewees living by themselves. Z.Z. from St. Petersburg said that she had never been so lonely and had never experienced anything similar in intensity to the solitude she now felt (May 2020). Referring to her loneliness, D.S. from London said: “There isn't enough distraction by having other people around, to be looking inwardly. It's too much time for self-reflection and thinking back at” (May 2020).

Even for those living with their spouses or other relatives, having to lock themselves in as part of the high-risk group represented not only the critical situation in their country, but also their self-image as elders, as expressed by T.P. from St. Petersburg: “It is not pleasant to be aware of your age.” Chronological age often did not match the interviewees’ health condition, vitality, and self-perception. According to D.S., “I am really 24 in every way,” but being associated with the age at risk made her think, “I am old, I am actually old” (M.S., A.A., May–June 2020). It appeared that women were more forthcoming in revealing their anxieties and their fear of dying from the virus, while the men tended to conceal their worries. However, E.L. of Rio de Janeiro disclosed that because of COVID-19 he started fearing death and was considering making arrangements for his family. On the other hand, L.G. of London said sarcastically, “I am at the risk of dying anyway just because I am 84, soon to be 85, you know it’s not a big deal” (E.L., L.G., B.K., D.S., M.Y., T.P., M.S., H.V., May–June 2020).

A few interviewees were directly affected by COVID-19, as they or their close relatives were infected. The first Israeli victim of the virus resided in Nofim, a Jerusalem nursing home that was caught unprepared (Heller 2020). M.M., a retired psychiatric nurse residing in Nofim, volunteered to chair the home’s health committee and dedicated herself to the problems of her companions in quarantine: “Since I was busy from seven in the morning until ten in the evening I had no time to think of myself,” she said, and thus she ignored her own infection. She was taken to the hospital, which she described as “a hallucinatory place where everybody is dressed in white [and…] everything is done through computers and television, you don't see people.”

Most interviewees had some contact with people who had died of or recovered from COVID-19, but their experience under the pandemic was basically related to their own seclusion, and they stated that their relations with their family helped them cope. R.G. from Milan said that she loves to hug, but because of the situation she tried to talk a lot on the phone in order not to lose the human touch. R.K. added that Milan seniors whose children lived abroad had more access to remote communication, but there were many who did not know how to use WhatsApp, Zoom, or a tablet, and thus experienced greater solitude (R.K. & R.G., May 2020). In many families, holidays and birthdays celebrated via Zoom helped maintain family cohesion. Although not religious, E.P.’s family in Rio de Janeiro celebrated the Sabbath and the Passover Seder via Zoom: “In certain respects, the family is more united now.”

Some interviewees mentioned that despite the social distance they were able to meet their children on the threshold of their house or wave to their grandchildren from the window. D.S. from London compared herself with people of her age who could see occasionally their children and grandchildren, even if they could not touch them: “They are very connected within their family network and I am very conscious of my aloneness.”

Unlike D.S., S.H.M. from Milan was surrounded by members of her family during the lockdown, but she joked that their protectiveness made her feel like a sort of a prisoner in her own house. Some interviewees, however, considered this period as an opportunity for relaxation and for finding new sources of empowerment. D.B., an 81-year-old from Jerusalem, said that it was a very pleasant period. Instead of “racing with time,” he enjoyed sitting calmly, looking at the sky and the trees without stress. His staying at home deepened his relations with his wife.

Despite their age, several interviewees still worked, mostly from home. Others took courses, listened to lectures, or participated in various activities via Zoom. Cellist M.S. from New York taught children and adults through Zoom, Skype, and FaceTime. She said that she enjoyed not having excuses to go out, and was busier than before. M. K., a psychoanalyst from Rio de Janeiro, treated her patients via Zoom. Aware of the disadvantages of online sessions, she said that “We have to get accustomed to being close without being close.” (M.K., Dr. F.C., May–June 2020).

Interviewees were asked whether traumatic experiences in their past had an impact on the way they were coping with COVID-19. Shoah survivors emphasized the enormous difference between the two situations. L.W.R. from Milan argued that we were not at war with COVID-19 since war occurs between human beings and “now we are all equal.” Referring to her past trauma, she said: “When I was a small child I was hidden here, on the lake, from 43 to 44. […] Then I had to hide from others; now I have to defend myself like all the others, so it is not the same thing.” L.G. from London said that his childhood experience during the Blitz had immunized him: “You know, if you’ve been Blitzed and evacuated and brought back and evacuated… I mean […] nearly six years of war—anything afterwards is, you know, a tea party. It’s not very serious.” He added that in a walk during lockdown he met an acquaintance who was a young child during the Shoah, and she said to him, “This too will pass,” expressing reconciliation with their old age, the risk of being infected and of passing away, but also the satisfaction of having lived a long and full life.

R.K. remarked that the survivors with whom she talked in the Milan community said that in comparison with what they had gone through during the war, COVID-19 was nothing. They seemed to her very calm, but she noticed that they were buying more food than usual. For M.K., born in a displaced persons (DP) camp in Germany, the revival of the memory of the Shoah under COVID-19 was focused around the use of Nazi symbols made by President Jair Bolsonaro, and she expressed her fear that his threats against individual rights would lead to fascism.

Some interviewees compared the current situation with other events in which the authorities tried to conceal their failure. Y.S. from St. Petersburg associated COVID-19 with Chernobyl, arguing that immediately after the 1986 nuclear reactor disaster the authorities assured the population that everything was under control and that they could go out as usual. Firefighters and soldiers were sent to their missions without protective suits, in the same way that the doctors in Russia remained without protective measures against the pandemic (Krassilchtchikova, June 2020). G.B. was reminded of the gas masks Israelis wore during the 1991 Gulf War, remarking that in both cases the masks were a meaningless fiction. Other interviewees mentioned cholera or polio outbreaks, the Arab siege of Jerusalem in 1948, and the 1967 pogrom in Libya.

In this new reality of global pandemic, the individuals’ daily lives were transformed. Actions that only a few days earlier were obvious, like meeting the children and grandchildren, sitting in a restaurant or café, going to a lecture or concert, meeting in the synagogue, or just being with friends, suddenly became the object of nostalgic memories. Feelings of fear or even anxiety were expressed during the interviews, but even at this time people shared dreams and hopes. When asked what they would do after the coronavirus, many described dreams of trivial activities such as going on vacation, dining out, celebrating with friends and family, playing bridge, shopping, or simply being spontaneous.

“Solidarity is Something that Was and that Continues:” The Jewish Community

Rabbi A.A., Milan.

COVID-19 created an unprecedented situation for Jews as individuals, but also as part of the Jewish world. Confronted by cases of disease and death, Jewish communities had to close their premises to protect their members.Footnote 13 They had to find new ways to support the sick and needy, most of whom were elderly people confined to their homes. Religious ceremonies, customs, and traditions had to be adapted to a new situation in which synagogues were closed and families divided. Congregations searched for new ways to continue religious services, to celebrate holidays and weddings, and to bury and commemorate their dead while keeping social distance.Footnote 14

Purim was the first challenge. Synagogues that avoided celebrating the holiday protected their members from being infected, while those who gathered for the reading of the Megillah helped spread the virus.Footnote 15 By Pesach it became clear how synagogues should act and what should be avoided. P.L., director of the radio station of the Fonds Social Juif Unifié (United Jewish Social Funds), said that the community media received information from the government, and they instructed the Jewish leadership to take precautions. All the important French rabbis called on their communities to avoid gathering, and to celebrate the Seder only with their nuclear families. L.L. from London had decided to stay at home before lockdown was imposed, and being “quite Orthodox” she decided to purchase products for Pesach ahead of time:

I went to the supermarket and there is a gentleman that I knew for years very very well, and he was there and none of the shelves had anything for Pesach yet, but the food was there […]. I said to him, this is ridiculous, so he said, “I will go to one direction and you will go in another, and when you see things we will tell each other.” […] two weeks later, he was dead.

Pesach during lockdown was a real challenge for Jews, who are used to celebrate the Seder around a large table in the company of family and friends. G.M. of Milan expressed the void created by the virus:

What hit us most, as a family… was not being able to do the Seder with the grandchildren, children, and friends, as we were used to. Friday night, not to be able to eat all together […] all these activities have disappeared.

Some interviewees celebrated traditionally with their nuclear family. Others communicated with their family via Zoom or other applications, thus being able to stay close also with their children abroad (Ms. M., L.L., B.M., D.A.G., M.S., May–June 2020). S.G. had an early Seder on Zoom with her son who lives in Israel, and a second one with her daughter in Rio de Janeiro. Some interviewees were more lenient in observing the Pesach customs, while others gave them up altogether.

For observant Jews, the closing of the synagogues was particularly difficult, profoundly transforming their lives. G.E. from Paris felt that not praying with fellow Jews made him feel troubled and alone since “the synagogue is not only a place of prayer but also for meeting friends.” Rabbi A.A. from Milan explained that praying was not only a religious duty but also fulfilled social needs:

Praying in Zoom is not the same thing […] one goes to the synagogue also to see people, one goes to the synagogue also to talk with somebody else. We complain that people chat idly, but in this moment, I would rather have people who chat; with the Zoom nobody chats.

Another religious custom that involves social gathering is the Kiddush, often accompanied by eating together. Interviewees noticed that they could not imagine how things would get back on track in the near future. Rabbi R.F. of New Jersey, who was sick with COVID-19 and hospitalized for 110 days, remarked that although the pandemic created a strong feeling of a close-knit community, he feared that social distance might dismantle the community if the situation would continue.

In Israel, neighbors organized spontaneous prayers from their balconies. V.B. from Bnei Brak described with excitement the temporary synagogues organized in her neighborhood. People standing in the courtyards, balconies, and even in the street gathered three times a day for praying. They took out the Torah scroll for Sabbath services and celebrated other rituals, maintaining communal life.

Some Orthodox synagogues celebrated the coming of the Sabbath ahead of time via Zoom, giving their members a taste of singing together before they had to disconnect and light the candles. Liberal and Reform congregations held full Sabbath services via Zoom.Footnote 16 In Rio de Janeiro, the progressive Associação Religiosa Israelita (ARI) attracted more than 500 participants to its Friday night services; interviewees who regularly did not go to a synagogue felt the need to participate (Rabbi Y.G., A.V., H.V, June–July, 2020).

For observant Jews, joining Sabbath services via Zoom confronted them with the dilemma between desecration of the Sabbath and participation in communal events. L.L. from London shared her doubts with us:

I have had to adapt, like I wouldn’t have used Zoom on Chag [Jewish holiday] or Shabbat [Sabbath]. I never used the phone on Shabbat, but now I am doing that because I am alone and it’s important to hear a human voice. You can’t sit all day on a Saturday and I had to adapt […]. Maybe when it's over I will not do it anymore […] but at the moment I am a very pragmatic person and I know that in order to keep myself sane I need to talk with my daughter every day. I need to be able to have social contact and if the telephone is the only way I can do it, then now I do it whether it’s Shabbat or not.Footnote 17

J.A.B. from New York referred to the pragmatism of rabbis in the synagogues around him, who allowed people to contact them by phone on the Sabbath and holidays, since saving lives is more important than observing the Sabbath.

Synagogues maintained their contact with their communities by conducting all their educational activities online. Their classes attracted also people who look for some spiritual support during the pandemic:

[…] we dedicated ourselves to giving many more Shiurei Torah (Torah lessons), for people are in the houses and have much more time to learn […]. In the past two months we gave over 500 Shiurei Torah in Rio de Janeiro on Zoom […] 63 workshops, 749 Shiurei Torah for couples and 340 lessons for boys and girls, and […] 100 Shiurei Torah just for women. Altogether we had 16,000 people going through our Zoom in three months (Rabbi Y.G., June 2020).

A similar trend was also acknowledged in the interview with the Chief Rabbi of Milan, A.A., whose online classes were filled with people he had never seen before. Since similar experiences were reported in other communities, he started to think about the importance of reaching out to unaffiliated Jews: “We often speak of distant Jews; they are less distant than we think.” COVID-19 thus led him to understand the potential of using new media to establish contact with those unable to be physically present, expressing his hope that in the future he would be able to combine both.

Synagogues conducted Zoom activities also to sustain families in their difficult hours. E.L., a board member of the Chevra Kadisha (Burial Society) in Rio de Janeiro, explained that because of state regulations they were not allowed to wash the dead. Rabbis held funerals, but only first-degree relatives were allowed to attend. R.K. described the funeral of a woman in which none of her children was present. Interviewees expressed their deep sorrow for not being able to participate physically in funerals or to stay close to the mourners, but synagogues provided online services that facilitated communication between the public and mourners. M.K., whose elder son had passed away 1 year before the interview, described the Zoom memorial event organized by the ARI synagogue in Rio de Janeiro as a source of comfort and spiritual sustenance (G.E., Rabbi Y.G., H.V., M.K., June-July 2020). The social distance is completely opposed to the traditional mourning ceremonies, creating significant cognitive dissonance among the participants via Zoom. On the other hand, online funerals and visits are open to persons who in other circumstances could not have been able to attend (Wolens 2020; Wood 2020).

Using new technologies in communal life should be considered with respect to the different religious movements. While Reform and secular Jews (and sometimes Conservatives) hold online services during the Sabbath, the Orthodox act according to the Halacha. For ultra-Orthodox Jews (Haredim), who never use the internet, Sabbath or not, COVID-19 led to a restricted use of technological devices. Their schools give Zoom lessons, and children who do not have computers at home follow them from their phones (V.B., May 2020).

The spread of the pandemic in the ultra-Orthodox centers in Israel, New York, London, and Paris provoked public criticism that was also echoed by interviewees. Those who lived far from these communities ignored or were indifferent to this phenomenon, while others expressed anger against the ultra-Orthodox communities that they considered irresponsible in their behavior during the pandemic (D.A.G., C.D., May 2020). L.L., for example, argued that they think God will save them because they are special, and thus they do not comply with the instructions. She felt they did not care, and it enraged her.Footnote 18 Even though they understood the difficulties of living in crowded housing with big families, interviewees expressed their indignation with their conduct. A.A., a former activist of UJA (the New York Jewish Federation) explained that the ultra-Orthodox had limited scientific knowledge, since science was not studied in their school (Andrews 2019). A.A. also remarked that ultra-Orthodox mothers with many children enjoy some relief during the summer vacation, but this year the summer camps were canceled, and the difficulties of going out with so many children would only increase. Their conduct during the pandemic depends on their respective rabbis who decide whether to fulfill or violate the instructions and hold prayers, studies and funerals almost as before the pandemic.

While public opinion in Israel was critical of the ultra-Orthodox for being uncooperative with the state’s authorities (Shavit 2020), V.B. from Bnei Brak presented her personal experience among Orthodox Jews who followed the government’s instructions. She spoke enthusiastically about the soldiers of the Home Front Command, who brought to her doorstep packages of food and products for Pesach and praised their kindness and generosity. The mobilization of the soldiers for the ultra-Orthodox population that is generally opposed to military service perhaps foreshadows a possible change in the perception of the military by the ultra-Orthodox (Branski 2017).

Jewish communities around the world regularly take care of the needy among their elders. Obviously, COVID-19 increased the number of persons in need. Kitchen soups that supplied food to elderly people without a family had to adapt. In Paris, youth volunteers supplied food from kosher restaurants and kitchen soups (P.L., June 2020). A.V., President of the Jewish Federation of Rio de Janeiro (FIERJ), said that the 60 Jewish organizations in the city established a Crisis Committee. Young volunteers shopped for those unable to go out, and the community provided medicines, food, and even money to people who had lost their job. Representatives of the Rio de Janeiro community, like those in Milan, were proud that in their old age homes nobody was infected—despite the severity of the outbreak in their countries.

In the Milan community, many elderly members are Shoah survivors who need warmth and affection and seek it through frequent phone calls (R.K.& R.G., M.D.P., May 2020). While describing the situation during the first lockdown, interviewees expressed their concern about the economic crisis that would ensue, with serious consequences for individual Jews and consequently also for Jewish institutions.

Since the outbreak of the coronavirus and especially due to the social distance regulations, people crave a sense of belonging. According to the interviews, Jews found this sense of belonging in the community. Some had to adapt and use technology to continue their contact with the community, while for others the pandemic opened new opportunities to approach Jewish communal life. The spontaneous reaction to the lockdown and the social distance was to unite as a community and reach out to connect and help others, but the continuous social distance may also lead to disintegration. This article raises the question of the possible impact of the pandemic on the future of the Jewish communities.Footnote 19

“It has Created the Feeling of People Helping People:” The Jewish Community and Wider Society

Rabbi R.F., New York.

COVID-19 does not distinguish between ethnic groups, but crises tend to uncover undercurrents that shed light on minorities and their image. Interviewees in our study pointed out the prominent place of Jews in the medical systems of their respective countries,Footnote 21 their high socioeconomic status, their particular political tendencies, as well as open or latent antisemitism. At the same time, the interviewees reflected the general public opinion with respect to the way their national authorities dealt with the pandemic.

The critical or supportive attitude of interviewees towards governments and official media reflect the different contexts in which they live. Many referred to the different sources of information—local radio and television stations, foreign newspapers accessed through the internet, and reports received from friends and colleagues abroad. During many hours of solitude, people feel the need for information to understand their situation, but on the other hand, an interminable flow of information and speculations may cause confusion because the information often contradicts itself causing restlessness and anxiety. As L.L. put it, “it makes me ill.”Footnote 22

Interviewees in St. Petersburg expressed lack of confidence in their political system and official media, and their constant search for alternative sources of information. M.S. said she listened to the Russian official and unofficial radio channels, read the internet, and sometimes watched television. She compared all these news sources, but had come to understand that it is impossible to believe any of the media, and that she had to use her own judgment to understand what is really happening. O.Y. said that as a Soviet citizen she was used to not believing official statistics reported in the media, and as of May 2020, she did not believe that the number of infected persons in Russia was as low as reported.

M.R. from Berlin noticed that daily updates provided by Germany’s public health institute were delivered in a professional but simple language, and created a vital separation between the political and the professional ranks, so that politicians were not part of the medical aspects of the pandemic.

Some of the interviewees in London and New York criticized the way their governments dealt with the pandemic. The hesitance of Boris Johnson and the attitude of Donald Trump resulted in a massive spread of the virus, and convinced interviewees that they should exercise their own judgment. A similar attitude was reflected in many of the interviews from Rio de Janeiro that criticized President Bolsonaro for disregarding the risks of the pandemic, appearing in public without a mask and not keeping social distance. They distinguished between the lack of instructions by the federal government and the more restrictive state and municipal authorities, but like in St. Petersburg, they generally trusted foreign sources and common sense (D.A.G., M.K., E.P, H.V., May–June 2020).

Parisian interviewees trusted official information sources, but were critical of the slowness with which their government took measures against the pandemic. A.K. argued that while the president said they were at war, instead of enlisting the French industry and laboratories he relied on Chinese products. Like others, she pointed out the strictness with which the French police enforced regulations. People were allowed to leave their home only after filling out forms authorized by the police, and even people who went out to buy a croissant were fined. According to A.K., demonstrations were prohibited, people felt under surveillance, and “the police is tough and brutal.”Footnote 23

More than any other city in this study, Milan was hit hard by the first wave of COVID-19. Interviewees did not question the information transmitted by the official media, but were critical about the lack of medical infrastructure, which resulted in a tremendous burden on the intensive care departments and left many patients without treatment. In addition, there were shortages of medical supplies and long queues in pharmacies and supermarkets (G.M., F.C., R.T., June 2020).

While interviewees were critical of the way their governments handled the pandemic, many expressed their appreciation for the way the Israeli government functioned during the first wave (March to June 2020). Interviewees in New York, London, and St. Petersburg expressed their confidence and trust in the Israeli government, which acted firmly both in imposing the national lockdown and in its swift reaction. Some of the Russian interviewees noted that the Israeli reaction made them feel closer to Israel, and even consider immigrating there when the pandemic is over (D.S., O.Y., M.S., G.Y., June 2020).

One of the issues that drew our attention was the relation between the socioeconomic situation and the impact of COVID-19. The most outstanding case is that of Rio de Janeiro, where the first victims belonged to the wealthier classes, but very quickly the pandemic spread to the lower social strata. R.L. analyzed the statistics according to neighborhoods, and concluded that the impact of the pandemic on Jews was similar to that of their neighbors of the middle and upper middle class. Morbidity and mortality were much higher among the lower classes who did not obey the lockdown instructions, being forced to continue working outside their homes and to use public transportation. Most of the interviewees in Rio de Janeiro were conscious of their privileged situation and donated to welfare organizations that distributed food and other products in the favelas (R.L.& L.L.; E.P., E.L., D.A.G., H.V., and A.V., May–July 2020). Psychoanalyst M.K. was also active in a nongovernmental organization (NGO) that offered free psychological treatment to doctors and nurses, often traumatized by their helplessness in confronting the pandemic.

In Europe and New York, non-Jewish society is less polarized than in Brazil, and the fact that the Jews are an integral part of the general population seems more evident; thus, only few interviewees referred to the links between the coronavirus and the socioeconomic situation. G.M. noted that Jews were not an elite, and that what happened in the Jewish community reflected the general situation in Italy. He also referred to the assistance granted to immigrants during the pandemic in the framework of interreligious cooperation. Milan Jews were also active in raising funds for hospitals and charities (G.M., M.D.P., R.K.& R.G., May 2020).

While the economic crisis was only at its inception when we conducted the interviews, interviewees were asked about possible manifestations of antisemitism. A.A. from New York said that “Antisemitism is inevitable,” and other interviewees agreed that antisemitism does not need a pretext, since it is always latent, waiting to erupt. Nevertheless, there was no perception that antisemitism was rising in any of the diasporas in our study. The demonstrations that took place in London, New York, and Berlin were considered as not related to antisemitism, despite their antisemitic undertones.

In Berlin, demonstrators spoke of a conspiracy behind COVID-19. M.R. and R.O. talked about demonstrations in which Bill Gates was mentioned as one who would become rich following the pandemic, but said that the word “Jews” was not explicitly mentioned, possibly for fear of being perceived as antisemites, but the message was clear.Footnote 24 J.A.B. from New York argued that there was a lot of antisemitism in the USA as well as in the world, and that he did not expect this to change; at the same time, he did not think that the pandemic contributed to the phenomenon (J.A.B., B.K.. June–July 2020).

Demonstrations were prohibited in France by the “Emergency Laws,” but nevertheless, riots against unemployment broke out in the “Arab sections” of Paris, possibly also related to the fact that mortality from COVID-19 reached its peak during Ramadan (A. & J.P.K., June 2020). An anonymous interviewee argued that Muslim demonstrators, “incited” by extreme-left activists, waved the Palestinian flag and shouted “death to the Jews.”

That period also saw the Purim celebrations, which deeply affected the Jewish community in France. The number of infected and seriously ill Jews kept rising, which also fueled various conspiracy theories in March and April. Mark Knobel, Head of the Research Department of CRIF (Representative Council of French Jewish Institutions—the umbrella organization of French Jewry), argued that antisemites appealed to a large and frightened audience, sitting at home and trying to understand why the pandemic was occurring (Antisemitic Conspiracy Theories, 2020; Wiesenthal Centre, 2020). One of the events that shocked the Jewish community in France was the publication of a cartoon with the character of Agnès Buzyn, a Jew who until recently had served as France’s Minister of Health, pouring poison into a well. With a clear reference to the Black Death, Buzyn’s figure was shown with a long nose and a crooked smile. Indeed, the general atmosphere was characterized by accusations of attempts by the Jewish elites in France and abroad to accumulate capital and make manipulative use of the virus. Having said that, some of the interviewees from Paris felt no real impact on the antisemitism in France, which in their opinion had always existed.

Brazilian interviewees did refer to a few minor episodes that could be attributed to antisemitism under the impact of COVID-19, but they were mainly concerned with the use of neo-Nazi discourse by the circles around Bolsonaro, as well as with the use of the Israeli flag by Evangelists supporting the president, creating a wrong impression—that could damage the community’s reputation in the future—that Israel supported the president (E.P., M.K., D.A.G., and A.V., May–July 2020).

Interviewees in Milan explained the lack of antisemitic incidents during the lockdown by the fact that “people don’t have time to think about it.” At the same time, they noticed xenophobia directed at the Chinese (R.K. & R.G.; G.M., S.H.M., May 2020). This new phenomenon was also seen in other countries. In St. Petersburg, interviewees noted that antisemitism was replaced by hatred towards immigrants from Asian former Soviet republics such as Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. O.Y. said that when the Mayor of St. Petersburg was asked why masks were not distributed freely, he answered that he did not want to donate masks to “those people,” namely migrant workers (O.Y., L.S., May 2020). The harassment of persons of Asian descent was manifested also in racist behavior towards Chinese in London (B.M., May 2020). Z.D. related that a client went into a store owned by a Chinese and told him that she would stop buying there because he was Chinese. The owner told her that he was born in England and had never been to China, but this did not convince the client. Z.D. added that Chinese in London and Manchester were affected by the fact that clients stopped buying in their stores or eating in their restaurants.

In the majority of the interviews, the interviewees did not indicate that the coronavirus caused an increase in manifestations of antisemitism. This was perceived by most as a given condition, which the pandemic did not change. Note also that even if most of the interviewees stated that their trust in the media was limited and they cross-referenced news, information, and guidelines in various media channels, they showed great willingness to help general society as much as they could. According to the interviewees, tolerance on the one hand and solidarity and mutual assistance on the other are now considered essential values on which civil society should be founded.

Conclusion

The objective of our project was to record in real time the way in which elderly Jews living in different social and political environments experience and interpret their personal experiences and perceptions during the global crisis created by COVID-19 that stigmatized them as a population at risk and made them conscious of their advanced age, thus changing their self-image. Relying on the methodology of oral history, we produced a corpus of oral histories as raw material for further studies, but at the same time we present some conclusions, based on the preliminary analysis of the interviews.

The interviewees in this study experienced the extremely unusual situation of seclusion, fear of being infected, uncertainty as to their economic future, concern for family members, and the difficulties of coping with daily problems without physical contact with others and no clear horizon. This situation brought people to think about the possible changes caused by COVID-19 and to reappraise what was important to them in general.

Thinking about their future after the pandemic, interviewees were aware that life would not be the same, and that they should draw a lesson from the changes they had gone through. At the same time, they were conscious of the limitations on their power to control their lives, or to guarantee that changes would persist. On the personal level, interviewees expressed their desire to be close to their children and grandchildren, but at the same time they understood that closeness had its limits, and that technical devices would continue to be present in their family life.

On the communal level, the interviewees understood the importance of solidarity, but also its limitations: people would support the needy in times of emergency, or participate in online activities when they have nothing better to do, but the influence of the Jewish community is limited. Like other institutions of civil society, it is based on voluntarism, and is nurtured by social and spiritual needs. It is possible for communal institutions to conduct at least part of their activities online, in order to attract new audience or overcome geographical distances, but the persistence of these activities depends on the needs and aspirations of their members.

Interviewees also referred to virtual communication as an important change expected in the general public space. More people would work, at least partly, from their homes. Schools and academic institutions would include online activities in their curricula. Efficiency, however, has its limits, and interviewees expressed their opinion that human contact cannot be substituted by technical devices.

Some interviewees concluded that COVID-19 had taught them to distinguish between what is superfluous and what is essential in life. They expressed their hope that people would become more tolerant, and show greater understanding towards others and more compassion for the needy. They felt their family relations became stronger, and that their Jewish community was more meaningful than they had thought. They search for a more spiritual content to their life, and find it in the Jewish community.

Several interviewees criticized their governments, whose failure to cope with COVID-19 also led them to reassess their politics. For example, the Israeli D.B. said: “I gave my soul to this country, but I feel it’s being stolen from me.”

Our interviews were not conducted at an end of a process, and the opinions and feelings of the interviewees may have changed since the loosening of restrictions and the emergence of the second wave in the spring and summer of 2020, leading in many countries to a new lockdown. The collected oral histories can be analyzed from different perspectives and shed light on subjects that were not addressed here. We hope, however, that further interviewing would contribute to a better understanding of the impact of COVID-19 on elderly Jews and their social environments.

Availability of data and material

All interviews are available for research exclusively in the Oral History Division of the Avraham Harman Research Institute of Contemporary Jewry.

Notes

L. L., London.

Scholars interested to obtain access to the oral histories are requested to contact the Oral History Division at the Harman Research Institute of Contemporary Jewry (ohd@savion.huji.ac.il).

About half (37) of the interviewees were aged between 65 and 74 years; 29 were 75+ (the oldest being 90) years; and the rest were younger or did not report their age. All interviews are part of the Oral History Division’s collection at the Avraham Harman Research Institute of Contemporary Jewry, Hebrew University of Jerusalem. For the profile of the interviewees, see Appendix.

In total, 5 interviews were conducted in Amsterdam, 8 in Berlin, 8 in London, 11 in Milan, 8 in New York, 5 in Paris, 13 in Rio de Janeiro, 10 in St. Petersburg, and 10 in Israel (in Bnei Brak, Jerusalem and Tel Aviv). Most interviews in Rio de Janeiro were conducted in English or Spanish, mixed with Portuñol—a mixture of Spanish and Portuguese.

In this paper we avoided the use of full names, citing only initials. Interviewees requesting anonymity are cited only by the initial of their first name.

Psychologists found out that video conversations diminish half of the symptoms of depression in comparison with emails or audio communication (Cave 2014, Sherman, Michikyan and Greenfield, 2013).

For more about the interviewer’s role, see Kaplan 2020.

The Diamond Princess was a cruise ship; while quarantined in Japan, COVID-19 spread quickly among its passengers, 15 of whom were Israelis.

For the relationship between activity and wellbeing, see Son et al. (2020)

For a global overview of the mortality among Jews in the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic from March to May 2020, see https://archive.jpr.org.uk/download?id=8964

The Cohen Center for Modern Jewish Studies and the Steinhardt Social Research Institute at the Brandeis University, conducted a survey among ten American Jewish communities to better the community resilience. See https://bir.brandeis.edu/bitstream/handle/10192/38952/brjc_cross_community_webinar_ppt_090320.pdf. On the connection between mantel resilience and religious faith, see: Pirutinsky, S., Cherniak, A.D. & Rosmarin, D.H. COVID-19, Mental Health, and Religious Coping Among American Orthodox Jews. J Relig Health 59, 2288–2301 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-020-01070-z

R.O. from Berlin told us that the president of her community canceled all Purim festivities, while the Dresden community celebrated as usual, with very dire consequences. L.L. of London also noted that Purim celebrations helped spread the virus.

Even before the outbreak of the pandemic, it was suggested that involvement in online religious communities contributed to the wellbeing of older persons. See Okun and Nimrod 2019.

A survey of Jews across the UK conducted by Institute of Jewish Policy Research (JPR) in July 2020 showed that older people felt uncomfortable attending in-person in Jewish community activities. Jews_and_Coronavirus_in_England_and_Wales.July_2020.pdf (jpr.org.uk).

E.B. from Amsterdam also expressed a similar opinion, saying that “they believe that Hashem [God] will protect them.”.

See about Jonathan Boyd’s research on the possibilities to preserve Jewish communal life during and after the pandemic: https://jpr.org.uk/documents/JPR_Brief.COVID-19.Mar_2021.Final.pdf

and see also Jotam Confino, From Antisemitism to Zoom Prayers, How COVID-19 Affected Europe’s Jewish Communities, Haaretz, 4 March 2021. https://www.haaretz.com/world-news/europe/.premium-from-antisemitism-to-zoom-prayers-how-covid-19-affected-europe-s-jewish-communities-1.9589359?lts=1615646876515

Dr. M.M., for example, is the Coordinator of the Crisis Cabinet of COVID-19 in the Hospital of the University of Rio de Janeiro.

See also Hollman, August 2020. On the impact of social media on stress in China during COVID-19, see Gao et al. (2020).

See also G.E., P.L., and E.

Note that Bill Gates was born and raised in a Protestant family, raising the question of who perceived him as Jewish: the demonstrators, the interviewees, or both?

References

Abrams, Lynn. 2010. Oral history theory. London and New York: Routledge.

Alessandro, Portelli. 2003. The order has been carried out: history, memory and meaning of a Nazi massacre in Rome. New York: Palgrave Press.

Andrews, Michelle. 2019. Why measles hits so hard within N.Y. Orthodox Jewish Community. KHN, March 11, 2019. https://khn.org/news/why-measles-hits-so-hard-within-n-y-orthodox-jewish-community/. (accessed 10 September 2020).

Boyd, Jonathan. 2021. Moving beyond COVID-19: What needs to be done to help preserve and enhance Jewish communal life? Institute for Jewish Policy Research. https://jpr.org.uk/documents/JPR_Brief.COVID-19.Mar_2021.Final.pdf. (accessed 18 March 2021).

Boyd, Jonathan, Carli Lessof and David Graham. 2020. The Coronavirus papers 1.1: Renew our days as of old: Will we go back to Jewish activities and events? Institute for Jewish Policy Research, https://www.jpr.org.uk/publication?id=17563. (accessed 29 September 2020).

Branski, Colonel (res.) Yonatan. 2017. Integrating without changing: Military service as a catalyst for Haredi integration in Israeli society. Jerusalem Institute for Strategy and Security, 31 October 2017. https://jiss.org.il/en/haredi-integration/. (accessed 15 September 2020).

Cave, Mark. 2014. What remains: Reflections on crisis oral history. In Listening on the edge: Oral History in the aftermath of crisis. Eds. Mark Cave and Stephen M. Sloan, New York: Oxford University Press.

Confino, Jotam. From antisemitism to Zoom prayers, how COVID-19 affected Europe’s Jewish communities. Haaretz, 4 March 2021. https://www.haaretz.com/world-news/europe/.premium-from-antisemitism-to-zoom-prayers-how-covid-19-affected-europe-s-jewish-communities-1.9589359?lts=1615646876515. (accessed 18 March 2021).

Gao, Junling, Pinpin Zheng, Yingnan Jia, Hao Chen, Yimeng Mao, Suhong Chen, et al. 2020. Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS One 15, no. 4 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231924. (accessed 10 September 2020).

Heller, Shlomi. 2020. The corona failure in the Nofim nursing home, Kol Hair, March 26, 2020 (Hebrew), https://www.kolhair.co.il/jerusalem-news/126628/. (accessed 21 September 2020).

Kaplan, Anna F. 2020. Cultivating supports while venturing into interviewing during COVID-19. The Oral History Review. https://doi.org/10.1080/00940798.2020.1791724. (accessed 10 September).

Kelly, Jason M. 2020. The COVID-19 oral history project: Some preliminary notes from the field. The Oral History Review. https://doi.org/10.1080/00940798.2020.1798257. (accessed 10 September).

Korichi Rodolphe, Delphine Pelle-de-Queral, Germaine Gazano, and Arnaud Aubert. 2008. Why women use makeup: Implication of psychological traits in makeup functions. Journal of Cosmetic Science 59 (March/April 2008): 127–137.

Okun, Sarit, and Galit Nimrod. 2019. Online religious communities and wellbeing in later life. Journal of Religion, Spirituality & Aging 32 (3): 268–287.

Passerini, Luisa. 1998. Work ideology and consensus under Italian fascism. In Robert Perks and Alistair Thomson (eds.), The Oral History Reader, Routledge: London and New York: 53–62.

Perks Robert and Alistair Thomson (eds.). 2015. The oral history reader, Routledge: London and New York, 3rd edition.

Pirutinsky, S., Cherniak, A.D. & Rosmarin. 2020, D.H. COVID-19, Mental health, and religious coping among American Orthodox Jews. J Relig Health 59, 2288–2301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-020-01070-z. (accessed 18 March 2021).

Portelli Alessandro. 1998. What makes oral history different, The Oral History Reader, Robert Perks & Alistair Thomson (eds.) London: Routledge, 63–74.

Shavit, Adiel. 2020. Petition submitted to the High Court of Justice: “It’s inconceivable that you can demonstrate without restriction, but cannot have ten people pray in the same place,” Kippa, April 5, 2020 (Hebrew). https://g.kipa.co.il/958284/l/. (accessed 28 September 2020).

Sherman, Lauren E., Minas Michikyan, and Patricia M. Greenfield. 2013. The effects of text, audio, video, and in-person communication on bonding between friends. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace 7 no. 2 (2013), Article 3. https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2013-2-3. (accessed 10 September 2020).

Son, Julie S., Galit Nimrod, Stephanie T. West, Megan C. Janke, Toni Liechty, and Jill J. Naar. 2020. Promoting older adults’ physical activity and social well-being during COVID-19. Leisure Sciences 2020: 2020. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2020.1774015. (accessed 28 September).

Staetsky, L. Daniel, Ari Paltiel, 2020, COVID-19 mortality and Jews: a global overview of the first wave of the coronavirus pandemic, March to May 2020, Institute for Jewish Policy Research, https://archive.jpr.org.uk/download?id=8964. (accessed 18 March 2021).

Wolens, Orna. 2020. The surprising beauty of a Zoom funeral, Jewish Journal, August 7, 2020. https://jewishjournal.com/commentary/columnist/320074/the-surprising-beauty-of-a-zoom-funeral/. (accessed 10 September 2020).

Wood, Poppy. 2020. Lockdown-era Zoom funerals are upending religious traditions—and they may change the way we grieve forever. Prospect, April 20, 2020. https://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/philosophy/funerals-during-lockdown-coronavirus-covid-religious-tradition-zoom-grief. (accessed 10 September 2020).

Antisemitic Conspiracy Theories, an Odious Symptom of the Virus Crisis in France. FR24 News, April 5, 2020, https://www.fr24news.com/a/2020/04/antisemitic-conspiracy-theories-an-odious-symptom-of-the-virus-crisis-in-france.html. (accessed 28 September 2020).

Wiesenthal Centre to French Interior Minister: “Your Colleague, Former Health Minister Agnès Buzyn, is a Target of online antisemitism,” Statement, March 25, 2020. https://www.friendsofsimonwiesenthalcenter.com/news/wiesenthal-centre-to-french-interior-minister-your-colleague-former-health-minister-agnes-buzyn-is-a-target-of-online-antisemitism. (accessed 28 September 2020).

Funding

Partial financial support was received from the Avraham Harman Research Institute of Contemporary Jewry and the Israel Oral History Association.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dr. Sharon Livne and Dr. Margalit Bejarano are the AD of the Project. They wrote the paper together.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix

Appendix 1: List of interviewees:

Initials (in order of last name's initial) | Place | Age (years) | Gender | Interview date | Interviewer | Marital status | Profession |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

D.A.G | Rio de Janeiro | 71 | Male | 20 May 2020 | Margalit Bejarano | Married | Economist |

J.A.B | New York | 82 | Male | 29 July 2020 | Sharon Rapaport | Married | Rabbi |

A.A | New York | 75 | Female | 15 June 2020 | Sharon Rapaport | Married | Social Project Manager |

A.A | Milan | 62 | Male | 11 May 2020 | Livia Tagliacozzo | Married | Rabbi |

D.B | Jerusalem | 81 | Male | 13 May 2020 | Margalit Bejarano | Married | Economist |

G.B | Tel Aviv | 83 | Female | 1 June 2020 | Margalit Bejarano | Widowed | Librarian & Archeologist |

V.B | Bnei Brak (Israel) | 75 | Female | 10 May 2020 | Judit Reifen Ronen | Married | Teacher & Librarian |

E.B | Amsterdam | 71 | Male | 3 August 2020 | Arije de Haas | Unknown | Community Administrator |

F.C | Milan | 78 | Female | 12 May 2020 | Livia Tagliacozzo | Married | Psychiatrist & Psychoanalyst |

C.D | Israel | unknown | Female | 13 May 2020 | Margalit Bejarano | Married | Prison Administrative |

M.D.P | Milan | 72 | Female | 14 May 2020 | Livia Tagliacozzo | Married | Feldenkrais Trainer |

Z.D | London | 75 | Female | 6 May 2020 | Sharon Rapaport | Widowed | Unknown |

E. (anonymous interviewee) | Paris | 81 | Female | 24 June 2020 | Dov Gedi | Married | Teacher |

G.E | Paris | 55 | Male | 11 June 2020 | Dov Gedi | Married | Teacher |

R.F | New York | 72 | Male | 10 August 2020 | Sharon Rapaport | Married | Rabbi |

S.G | Rio de Janeiro | unknown | Female | 28 June 2020 | Margalit Bejarano | Widowed | Unknown |

Y.G | Rio de Janeiro | unknown | Male | 15 June 2020 | Margalit Bejarano | Married | Rabbi |

L.G | London | 85 | Male | 11 May 2020 | Sharon Rapaport | Unknown | Screenwriter |

S.H.M | Milan | 74 | Female | 22 June 2020 | Livia Tagliacozzo | Widowed | Unknown |

S.H | Amsterdam | 75 | Female | 14 August 2020 | Arije de Haas | Married | Executive Secretary |

G.J. & S.V | Milan | 60 & 62 | Female & Male | 17 May 2020 | Livia Tagliacozzo | Married couple | School Administrator & technology |

B.K | New York | 79 | Female | 28 June 2020 | Sharon Rapaport | Widowed | Psychologist & Sociologist |

A.K. & J.P.K | Paris | 75 & 75 | Female & Male | 29 June 2020 | Margalit Bejarano | Married couple | Biologist, Physicist & Mathematician |

R.K. & R.G | Milan | 54 & 73 | Female & Female | 13 May 2020 | Margalit Bejarano | Married & Married | Social Worker & Publishing |

E.K | St. Petersburg | 70 | Female | 4 June 2020 | Sonya Kelbert | Unknown | Pediatrics |

M.K | Rio de Janeiro | 72 | Female | 14 June 2020 | Margalit Bejarano | Married | Psychoanalyst |

P.L | Paris | 60 | Female | 4 June 2020 | Dov Gedi | Unknown | Journalist |

E.L | Rio de Janeiro | 66 | Male | 4 June 2020 | Margalit Bejarano | Married | Economist |

L.L. & R.L | Rio de Janeiro | 65 & age unknown | Female & Male | 6 July 2020 | Margalit Bejarano | Married couple | Engineer & Engineer |

Initials | Place | Age (years) | Gender | Interview date | Interviewer | Marital status | Profession |

M. (anonymous interviewee) | London | 80 | Female | 14 June 2020 | Sharon Rapaport | Widowed | Unknown |

M.M | Jerusalem | 77 | Female | 7 May 2020 | Sara Benvenisti | Widowed | Psychiatric Nurse |

B.M | London | 77 | Male | 14 May 2020 | Sharon Rapaport | Married | Unknown |

G.M | Milan | 73 | Male | 13 May 2020 | Livia Tagliacozzo | Married | Physician |

M.M | Rio de Janeiro | age unknown | Male | 21 June 2020 | Margalit Bejarano | Married | Orthopedic Surgeon |

R.O | Berlin | 66 | Female | 17 May 2020 | Sara Benvenisti | Married | Teacher |

T.P | St. Petersburg | 72 | Female | 27 May 2020 | Sonya Kelbert | Married | Philologist |

E.P | Rio de Janeiro | 72 | Female | 7 June 2020 | Margalit Bejarano | Married | Sociologist |

M.R | Berlin | 71 | Male | 14 May 2020 | Judit Reifen Ronen | Widowed in relationship | Hotelier |

L.S | St. Petersburg | 74 | Male | 20 May 2020 | Sonya Kelbert | Married | Sexologist |

M.S | St. Petersburg | 70 | Female | 9 June 2020 | Sonya Kelbert | Unknown | Librarian |

M.S | New York | 70 | Female | 6 June 2020 | Margalit Bejarano | Divorced | Musician |

D.S | London | 77 | Female | 10 May 2020 | Sharon Rapaport | Single | Unknown |

R.T | Milan | 62 | Male | 3 June 2020 | Livia Tagliacozzo | Unknown | Hi-Tech |

H.V | Rio de Janeiro | 72 | Female | 7 June 2020 | Margalit Bejarano | Married | Journalist |

A.V | Rio de Janeiro | 60 | Male | 2 July 2020 | Margalit Bejarano | Unknown | Lawyer |

L.W.R | Milan | 79 | Female | 8 May 2020 | Livia Tagliacozzo | Married | Teacher |

G.Y | St. Petersburg | 74 | Male | 4 June 2020 | Sonya Kelbert | Married | Psychiatrist |

O.Y | St. Petersburg | 70 | Female | 14 May 2020 | Sonya Kelbert | Unknown | Chemist |

Z.Z | St. Petersburg | 84 | Female | 15 May 2020 | Sonya Kelbert | Single | Chemist |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Livne, S., Bejarano, M. “It’s Important to hear a Human Voice,” Jews under COVID-19: An Oral History Project. Cont Jewry 41, 185–206 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12397-021-09374-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12397-021-09374-2