Abstract

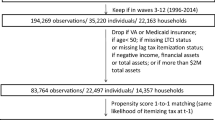

We evaluate the presence and magnitude of moral hazard in Japan’s public long-term care insurance (LTCI) market. Using monthly LTCI claim records from January 2006 to December 2015 linked to concurrent death records, we construct a sample by propensity score matching insured individuals who co-pay 10% of their fees to those with no required copayments, and we implement fixed-effect estimations. We find that a ten-percentage-point reduction in the copayment rate increases monthly costs by 10.2 thousand yen, corresponding to a price elasticity of about − 0.1. Insured individuals with no copayments tend to use more services and have more utilization days than those with copayments do. Furthermore, we find that insured individuals who die from cerebral (myocardial) infarction increase their service use more in response to a reduction in the copayment rate than those who die from senility do, indicating a positive association between ex-ante health risks and ex-post service use. We verify that a cost-sharing adjustment is a valid solution for soaring LTCI expenditures. These findings could provide broad implications for the rapidly aging world.

Refined by authors based on a figure from Explanation of long-term care insurance system (p. 9) by the Social Insurance Institute 2018 (in Japanese). ISBN978-4-7894-2594-0$4

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For primary insured individuals, premiums are collected through pension deductions or individual collections. For secondary insured individuals, premiums are collected together with HI premiums.

The care level is categorized as one of seven need levels from the mildest support required at level 1 (SL1) to the most severe care at level 5 (CL5). See Appendix A for details.

The committee consists of third-party physicians, nurses, and social workers.

The only information not related to health status regards living conditions (e.g., lift availability and co-residence). The investigator (a municipality official who organizes the interview) can leave comments in a column at the end of the questionnaire, labeled “Please leave a note here about applicant’s living condition if necessary.” The MHLW explicitly mentions that such information is “used for reference purposes only” and is “not used to determine/change care levels” [19, p. 18].

See Appendix B for details on the eligibility process for public assistance and the contents of the assistance.

The care plan consists of what and how many services to use within a month.

It is important to clarify that the care managers affiliated with the care centers are independent of service suppliers, and, thus, they are unlikely to recommend that insured individuals expand their care plans for financial purposes. Instead, it is highly risky for them to do so, because municipalities will rescind their designations and make monetary dispositions if they are aware of foul play. In contrast, care managers employed by either non-profit or for-profit service providers may have incentives to induce demand for long-term care. Unfortunately, we cannot identify the type of care manager (independent versus employee) support used to construct each individual’s care plan. Alternatively, we use the propensity score matching procedure (see Table 1) to adjust for the type of care manager by balancing the type of service supplier providing care most frequently, as an insured individual is most likely to be supported by a care manager who is affiliated with service provider that he uses most frequently.

For instance, people with poor SES are more likely to be unmarried [20]. Once become frail, these individuals may have to depend exclusively on formal long-term care services because they have few informal care alternatives.

An insured individual moving to a new municipality loses his eligibility in his previous place of residence and obtains new eligibility in his current place of residence. However, the probability of an elderly and disabled individual moving is very low.

In addition, we remove all the claims of insured individuals with incomes comparable to those of current workers, who transferred from the 10% to the 20% copayment scheme as of August 2015.

In 2017, about half of the population receiving PA in Japan were over 65 [24]. The proportions of those aged 40–49 (10.1%), 30–39 (5.5%), and 20–29 (2.8%) were much lower, probably because such individuals have more opportunities to work and, thus, are more likely to alleviate their poverty.

Causes of death are classified into 13 categories refined according to the international statistical classification of diseases and related health problems 10th Revision (ICD-10).

The number of individuals without PA extracted for the estimations varies across matching methods.

We do not use deaths from neoplasms or blood diseases for the cause-specific estimation because such diseases are likely associated with genetic rather than health risks.

According to a report of a public awareness investigation of healthcare and long-term care in 2017 [34], 40% of respondents aged 65 and over think that the copayment rate is “very low” or “low,” 28.7% say “neither low or high,” and 7.9% consider the rate to be “very high.” The corresponding rates for those younger than 65 are 29.8%, 37.9%, and 9.7%, respectively. The report concludes that the higher rate of “neither low or high” among the younger cohort is attributable to the lower prevalence of long-term care use therein (so that they do not know the costs). More importantly, the higher rates of “very low” and “low” among the older cohort show that, even for those who are much more likely to use the services, the cost sharing is moderate.

We observe a rather long period of service use (i.e., 120 months), during which individuals might be induced to re-construct their care plans.

References

Manning, W.G., Marquis, M.S.: Health insurance: the tradeoff between risk pooling and moral hazard. J. Health Econ. 15, 609–639 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-6296(96)00497-3

Finkelstein, A.: The aggregate effects of health insurance: evidence from the introduction of Medicare. Q. J. Econ. 122, 1–37 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.122.1.1

Keane, M., Stavrunova, O.: Adverse selection, moral hazard and the demand for Medigap insurance. J. Econometr. 190, 62–78 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2015.08.002

Zweifel, P., Manning, W.G.: Moral hazard and consumer incentives in health care. In: Culyer, A.J., Newhouse, J.P. (eds.) Handbook of Health Economics 1, Part A, pp. 409–459. North Holland, Amsterdam (2000). https://doi.org/10.1016/S1574-0064(00)80167-5

Finkelstein, A., McGarry, K.: Multiple dimensions of private information: evidence from the long-term care insurance market. Am. Econ. Rev. 96, 938–958 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.96.4.938

Braun, R., Kopecky, K.A., Koreshkova, T.: Old, frail, and uninsured: Accounting for puzzles in the US long-term care insurance market. FRB Atlanta Working Paper No. 2017-3 (2017). https://ssrn.com/abstract=2940588. Accessed 4 Dec 2018

Brown, J.R., Finkelstein, A.: Why is the market for long-term care insurance so small? J. Publ. Econ. 91, 1967–1991 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2015.05.009

Campbell, J.C., Ikegami, N.: Long-term care insurance comes to Japan. Health Aff. 19, 26–39 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.19.3.26

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare: Long-Term Care Insurance System of Japan (2016). http://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/policy/care-welfare/care-welfare-elderly/dl/ltcisj_e.pdf. Accessed 3 July 2018

National Health Policy Forum: The Basics: National Spending for Long-Term Services and Supports (2014). http://www.nhpf.org/library/the-basics/Basics_LTSS_03-27-14.pdf. Accessed 27 July 2017

Reich, M.R., Shibuya, K.: The future of Japan’s health system—sustaining good health with equity at low cost. New Engl. J. Med. 373, 1793–1797 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1410676

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare: Handbook of Health and Welfare Statistics 2016 (2016). https://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/database/db-hh/5-1.html. Accessed 5 July 2018

Rothschild, M., Stiglitz, J.: Equilibrium in competitive insurance markets: an essay on the economics of imperfect information. Q. J. Econ. 90, 629–649 (1976). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-015-7957-5_18

Ellis, R.P., McGuire, T.G.: Predictability and predictiveness in health care spending. J. Health Econ. 26, 25–48 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2006.06.004

Ehrlich, I., Becker, G.S.: Market insurance, self-insurance, and self-protection. J. Polit. Econ. 80, 623–648 (1972). https://doi.org/10.1086/259916

Dave, D., Kaestner, R.: Health insurance and ex ante moral hazard: evidence from Medicare. Int. J. Health Care Finance Econ. 9, 367 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10754-009-9056-4

Klick, J., Stratmann, T.: Diabetes treatments and moral hazard. J. Law Econ. 50, 519–538 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1086/519813

Trujillo, A.J., VecinoOrtiz, A.I., RuizGómez, F., Steinhardt, L.C.: Health insurance doesn’t seem to discourage prevention among diabetes patients in Colombia. Health Aff. 29, 2180–2188 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0463

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare: Textbook for long-term care investigators. (in Japanese) (2018). https://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/06-Seisakujouhou-12300000-Roukenkyoku/0000077237.pdf. Accessed 23 Nov 2018

Schneider, D., Hastings, O.P.: Socioeconomic variation in the effect of economic conditions on marriage and nonmarital fertility in the United States: evidence from the Great Recession. Demography 52, 1893–1915 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-015-0437-7

Savage, E., Wright, D.J.: Moral hazard and adverse selection in Australian private hospitals: 1989–1990. J. Health Econ. 22, 331–359 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-6296(02)00104-2

Finkelstein, A., Taubman, S., Wright, B., Bernstein, M., Gruber, J., Newhouse, J.P., Oregon Health Study Group: The Oregon health insurance experiment: evidence from the first year. Q. J. Econ. 127, 1057–1106 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjs020

Manning, W.G., Newhouse, J.P., Duan, N., Keeler, E.B., Leibowitz, A.: Health insurance and the demand for medical care: evidence from a randomized experiment. Am. Econ. Rev. 1, 251–277 (1987)

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare: Current Situation of Public Assistance. (in Japanese) https://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/05-Shingikai-12601000-Seisakutoukatsukan-Sanjikanshitsu_Shakaihoshoutantou/0000164401.pdf (2017). Accessed 4 Dec 2018

Rosenbaum, P.R.: The consequences of adjustment for a concomitant variable that has been affected by the treatment. J. R. Stat. Soc. 147, 656–666 (1984)

Tokunaga, M., Hashimoto, H., Tamiya, N.: A gap in formal long-term care use related to characteristics of caregivers and households, under the public universal system in Japan: 2001–2010. Health Pol. 119, 840–849 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.10.015

Ishii, S., Ogawa, S., Akishita, M.: The state of health in older adults in Japan: trends in disability, chronic medical conditions and mortality. PloS One 10(10), e0139639 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0139639

Wolff, J.L., Barbara, S., Gerard, A.: Prevalence, expenditures, and complications of multiple chronic conditions in the elderly. Arch. Intern. Med. 162, 2269–2276 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.162.20.2269

Caliendo, M., Kopeinig, S.: Some practical guidance for the implementation of propensity score matching. J. Econ. Surv. 22, 31–72 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6419.2007.00527

Austin, P.C.: An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behav. Res. 46, 399–424 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2011.568786

Kan, M., Suzuki, W.: Effects of cost sharing on the demand for physician services in Japan: Evidence from a natural experiment. Jpn. World Econ. 22, 1–12 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.japwor.2009.06.005

Shigeoka, H.: The effect of patient cost sharing on utilization, health, and risk protection. Am. Econ. Rev. 104, 2152–2184 (2014)

Nyman, J.A.: The economics of moral hazard revisited. J. Health Econ. 18, 811–824 (1999)

National Federation of Health Insurance Societies: Report of Public Awareness Investigation about the Healthcare and Long-term Care. https://www.kenporen.com/include/press/2017/20170925_8.pdf (2017). Accessed 7 Dec 2018

Campbell, J.C., Ikegami, N., Gibson, M.J.: Lessons from public long-term care insurance in Germany and Japan. Health Aff. 29, 87–95 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0548

Hiltunen, S., Putaala, J., Haapaniemi, E., Tatlisumak, T.: Long-term outcome after cerebral venous thrombosis: analysis of functional and vocational outcome, residual symptoms, and adverse events in 161 patients. J. Neurol. 263, 477–484 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-015-7996-9

Acknowledgements

This study is financially supported by several funds: the Waseda University Research Initiative entitled “Empirical and theoretical research for social welfare in sustainable society- Inheritance of human capital beyond ‘an individual’ and ‘a generation’”—(PI: Haruko Noguchi); a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research Project funded by the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare (MHLW): “Effects of the prevention policy of lifestyle-related disease on labor productivity and the macroeconomy from the viewpoint of cost-effective analysis” (PI: Haruko Noguchi); a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research(C) funded by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS): “Change and disparity in accessibility to long-term care services: Evidence from Japanese big data analyses” (PI: Akira Kawamura); and a Grant-in-Aid for Stat-up funded by JSPS: “The effect of the 2006 long-term care insurance amendment on cost containment: empirical evidence from nationally representative claims data.” (PI: Rong Fu). This study has received official approval for the use of secondary data from the Statistics and Information Department of the MHLW under Tohatsu-0507-3 as of May 7, 2018. We greatly appreciate Dr. Michihito Ando for his helpful comments at the Japan Economic Association 2018 Spring Meeting. Our thanks also go to participants in the European Health Economics Association at Maastricht, The Netherlands, in July 2018 for their valuable suggestions. In addition, we deeply appreciate the two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions on this study. The views and opinions expressed in this article by the independent authors are provided in their personal capacity and are their sole responsibility.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fu, R., Noguchi, H. Moral hazard under zero price policy: evidence from Japanese long-term care claims data. Eur J Health Econ 20, 785–799 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-019-01041-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-019-01041-6