Abstract

Purpose of Review

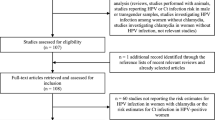

Interactions between microorganisms can alter subsequent disease outcomes. Human papilloma virus (HPV) and Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) establish human genital co-infections, and CT infection is a co-factor for HPV-induced cervical cancer. This review focuses upon (i) data indicating that clinically significant interactions occur and (ii) proposed mechanisms underlying these outcomes.

Recent Findings

Epidemiological surveys indicate that (i) simultaneous HPV/CT genital co-infections are common; (ii) CT co-infection accelerates HPV-induced cytopathology; and (iii) HPV infection facilitates CT infection. Single-infection studies suggest specific molecular mechanisms by which co-infection alters clinical outcomes, including (i) HPV E6/E7 protein modification of host cell pathways enhances CT replication or immune evasion and (ii) CT-mediated host cell or neutrophil dysfunctions promote HPV-mediated neoplasia.

Summary

There are multiple avenues for future dissection of HPV/CT interactions. Moreover, the known and potential health consequences of co-infection highlight the need for improving current HPV vaccines and developing an effective CT vaccine.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

• Karim S, Souho T, Benlemlih M, Bennani B. Cervical cancer induction enhancement potential of Chlamydia trachomatis: a systematic review. Curr Microbiol. Springer US; 2018 [cited 2019 Jan 10];75:1667–74. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00284-018-1439-7. A concise recent review of chlamydia/HPV potentiation of cervical cancer induction focused on epidemiologic and clinical studies.

WHO 2018 Report on global sexually transmitted infection surveillance. World Heal. Organ. 2018 [cited 2019 Jan 3];1–74. Available from: http://apps.who.int/bookorders.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Sexually transmitted disease surveillance. 2017 [cited 2019 Feb 5]; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats17/2017-STD-Surveillance-Report_CDC-clearance-9.10.18.pdf

Trebach JD, Chaulk CP, Page KR, Tuddenham S, Ghanem KG. Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis among women reporting extragenital exposures. Sex. Transm Dis. 2015 [cited 2015 Oct 28];42:233–9. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25868133.

Javanmard D, Behravan M, Ghannadkafi M, Salehabadi A, Ziaee M, Namaei MH. Detection of Chlamydia trachomatis in Pap smear samples from South Khorasan Province of Iran. Int J Fertil Steril. Royan Institute; 2018 [cited 2019 Jan 10];12:31–6. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29334204.

Harder E, Thomsen LT, Frederiksen K, Munk C, Iftner T, van den Brule A, et al. Risk factors for incident and redetected Chlamydia trachomatis infection in women. Sex Transm Dis. 2016 [cited 2019 Feb 8];43:113–9. Available from: https://insights.ovid.com/crossref?an=00007435-201602000-00010

Aghaizu A, Reid F, Kerry S, Hay PE, Mallinson H, Jensen JS, et al. Frequency and risk factors for incident and redetected Chlamydia trachomatis infection in sexually active, young, multi-ethnic women: a community based cohort study. Sex Transm Infect. 2014 [cited 2019 Feb 8];90:524–8. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25100744.

Unemo M, Bradshaw CS, Hocking JS, de Vries HJC, Francis SC, Mabey D, et al. Sexually transmitted infections: challenges ahead. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017 [cited 2019 Feb 26];17:e235–79. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1473309917303109

•• Phillips S, Quigley BL, Timms P. Seventy years of chlamydia vaccine research - limitations of the past and directions for the future. Front Microbiol. 2019 [cited 2019 Feb 26];10:70. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmicb.2019.00070/full. An excellent recent summary of chlamydial diseases, mechanisms of immune protection, and progress toward development of chlamydial vaccines in humans and non-human animals.

Geisler WM, Uniyal A, Lee JY, Lensing SY, Johnson S, Perry RCW, et al. Azithromycin versus doxycycline for urogenital Chlamydia trachomatis infection. N Engl J Med. Massachusetts Medical Society; 2015 [cited 2018 Mar 23];373:2512–21. Available from: http://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa1502599

Suchland RJ, Dimond ZE, Putman TE, Rockey DD. Demonstration of persistent infections and genome stability by whole-genome sequencing of repeat-positive, same-serovar Chlamydia trachomatis collected from the female genital tract. J Infect Dis. 2017 [cited 2019 Feb 26];215:1657–65. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jid/article/215/11/1657/3079217

Redgrove KA, McLaughlin EA. The role of the immune response in Chlamydia trachomatis infection of the male genital tract: a double-edged sword. Front Immunol. Frontiers Media SA; 2014 [cited 2016 Aug 23];5:534. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25386180.

Paavonen J, Teisala K, Heinonen PK, Aine R, Miettinen A, Lehtinen M, et al. Endometritis and acute salpingitis associated with Chlamydia trachomatis and herpes simplex virus type two. Obstet Gynecol. 1985 [cited 2016 Mar 10];65:288–91. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2982116.

Malhotra M, Sood S, Mukherjee A, Muralidhar S, Bala M. Genital Chlamydia trachomatis: an update. Indian J Med Res. 2013 [cited 2015 Feb 20];138:303–16. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3818592&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract

Price MJ, Ades A, Soldan K, Welton NJ, Macleod J, Simms I, et al. Duration of asymptomatic Chlamydia trachomatis infection. NIHR Journals Library; 2016 [cited 2019 Feb 8]; Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK350655/

Ljubin-Sternak S, Meštrović T. Chlamydia trachomatis and genital mycoplasmas: pathogens with an impact on human reproductive health. J Pathog. 2014 [cited 2019 Feb 26];2014:183167. Available from: http://www.hindawi.com/journals/jpath/2014/183167/

Menon S, Timms P, Allan JA, Alexander K, Rombauts L, Horner P, et al. Human and pathogen factors associated with Chlamydia trachomatis-related infertility in women. Clin Microbiol Rev. American Society for Microbiology (ASM); 2015 [cited 2017 Feb 11];28:969–85. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26310245.

Wyrick PB. Chlamydia trachomatis persistence in vitro: an overview. J Infect Dis. Oxford University Press; 2010 [cited 2017 Jan 18];S88–95. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20470046.

Moore ER, Ouellette SP. Reconceptualizing the chlamydial inclusion as a pathogen-specified parasitic organelle: an expanded role for Inc proteins. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. Frontiers Media SA; 2014 [cited 2018 Jun 29];4:157. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25401095.

Hybiske K, Stephens RS. Mechanisms of host cell exit by the intracellular bacterium Chlamydia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 [cited 2016 Feb 28];104:11430–5. Available from: http://www.pnas.org/content/104/27/11430.full

Beatty WL, Belanger TA, Desai AA, Morrison RP, Byrne GI. Tryptophan depletion as a mechanism of gamma interferon-mediated chlamydial persistence. Infect Immun. American Society for Microbiology Journals; 1994 [cited 2019 Feb 11];62:3705–11. Available from: https://iai.asm.org/content/62/9/3705.short

Kintner J, Lajoie D, Hall J, Whittimore J, Schoborg RV. Commonly prescribed β-lactam antibiotics induce C. trachomatis persistence/stress in culture at physiologically relevant concentrations. Front. Cell Infect Microbiol. 2014 [cited 2015 Sep 29];4:44. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3990100&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract.

Galasso GJ, Manire GP. Effect of antiserum and antibiotics on persistent infection of HeLa cells with meningopneumonitis virus. J Immunol. 1961 [cited 2016 Mar 10];86:382–5. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/13703027.

• Panzetta ME, Valdivia RH, Saka HA. Chlamydia persistence: a survival strategy to evade antimicrobial effects in-vitro and in-vivo. Front Microbiol. Frontiers; 2018 [cited 2019 Feb 20];9:3101. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.03101/full. An incisive recent review of the chlamydial stress response focused specifically on anti-microbial drug evasion.

•• Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA. Cancer J Clin. American Cancer Society; 2018 [cited 2019 Jan 12];68:394–424. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21492. Current cancer global incidence and mortality statistics.

WHO. WHO | Progress report of the implementation of the global strategy for prevention and control of sexually transmitted infections: 2006–2015. WHO World Health Organization; 2015.

Bzhalava D, Eklund C, Dillner J. International standardization and classification of human papillomavirus types. Virology. Academic Press; 2015 [cited 2019 Jan 12];476:341–4. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0042682214005777

Costa-Lira E, Jacinto AHVL, Silva LM, Napoleão PFR, Barbosa-Filho RAA, Cruz GJS, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus, Chlamydia trachomatis, and Trichomonas vaginalis infections in Amazonian women with normal and abnormal cytology. Genet Mol Res. 2017 [cited 2019 Jan 10];16. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28453175.

Marcellusi A, Capone A, Favato G, Mennini FS, Baio G, Haeussler K, et al. Health utilities lost and risk factors associated with HPV-induced diseases in men and women: the HPV Italian Collaborative Study Group. Clin Ther Elsevier; 2015 [cited 2019 Feb 8];37:156–67.e4. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0149291814007346.

Moscicki A-B, Schiffman M, Kjaer S, Villa LL. Chapter 5: Updating the natural history of HPV and anogenital cancer. Vaccine. 2006 [cited 2019 Feb 26];24 Suppl 3:S3/42–51. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0264410X06007328

Wright TC, Ronnett BM, Kurman RJ, Ferenczy A. Precancerous lesions of the cervix. Blaustein’s Pathol. Female Genit Tract. Boston, MA: Springer US; 2011 [cited 2019 Jan 15]. p. 193–252. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-0489-8_5

•• McBride AA, Warburton A. The role of integration in oncogenic progression of HPV-associated cancers. Spindler KR, editor. PLOS Pathog. Public Library of Science; 2017 [cited 2019 Jan 13];13:e1006211. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1006211. A recent review on the role of HPV integration in cancer progression.

Schwarz E, Freese UK, Gissmann L, Mayer W, Roggenbuck B, Stremlau A, et al. Structure and transcription of human papillomavirus sequences in cervical carcinoma cells. Nature. 1985 [cited 2019 Feb 26];314:111–4. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2983228.

Chen Y, Williams V, Filippova M, Filippov V, Duerksen-Hughes P. Viral Carcinogenesis: factors inducing DNA damage and virus integration. Cancers (Basel). 2014 [cited 2019 Feb 26];6:2155–86. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25340830.

Graham SV. The human papillomavirus replication cycle, and its links to cancer progression: a comprehensive review. Clin Sci (Lond). Portland Press Limited; 2017 [cited 2019 Feb 8];131:2201–21. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28798073.

Münger K, Howley PM. Human papillomavirus immortalization and transformation functions. Virus Res. Elsevier; 2002 [cited 2019 Jan 12];89:213–28. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0168170202001909.

Senapati R, Senapati NN, Dwibedi B. Molecular mechanisms of HPV mediated neoplastic progression Infect. Agent. Cancer [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2019 Feb 26];11:59. Available from: http://infectagentscancer.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13027-016-0107-4

•• Ji Y, Ma X, Li Z, Peppelenbosch MP, Ma Z, Pan Q. The Burden of human papillomavirus and Chlamydia trachomatis coinfection in women: a large cohort study in inner Mongolia, China. J. Infect. Dis. [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Jan 10];219:206–14. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30192954. The most recent epidemiological study examining both prevalence of HPV/CT co-infection and association of co-infection with abnormal cytology.

Mancini F, Vescio F, Mochi S, Accardi L, di Bonito P, Ciervo A. HPV and Chlamydia trachomatis coinfection in women with Pap smear abnormality: baseline data of the HPV Pathogen ISS study. Infez. Med. [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Jan 10];26:139–44. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29932086.

Lima L, Hoelzle C, Simões R, Lima M, Fradico J, Mateo E, et al. Sexually transmitted infections detected by multiplex real time PCR in asymptomatic women and association with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Rev. Bras. Ginecol. e Obs. / RBGO Gynecol. Obstet. [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Jan 12];40:540–6. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30231293.

Menezes LJ, Pokharel U, Sudenga SL, Botha MH, Zeier M, Abrahamsen ME, et al. Patterns of prevalent HPV and STI co-infections and associated factors among HIV-negative young Western Cape, South African women: the EVRI trial. Sex. Transm. Infect. [Internet]. BMJ Publishing Group Ltd; 2018 [cited 2019 Jan 12];94:55–61. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28490581.

Zhang D, Li T, Chen L, Zhang X, Zhao G, Liu Z. Epidemiological investigation of the relationship between common lower genital tract infections and high-risk human papillomavirus infections among women in Beijing, China. PLoS One [Internet]. Public Library of Science; 2017 [cited 2019 Jan 10];12:e0178033. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28531212.

Bianchi S, Boveri S, Igidbashian S, Amendola A, Urbinati AMV, Frati ER, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis infection and HPV/Chlamydia trachomatis co-infection among HPV-vaccinated young women at the beginning of their sexual activity. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2019 Jan 10];294:1227–33. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27501926.

Melo A, Lagos N, Montenegro S, Orellana JJ, Vásquez AM, Moreno S, et al. Virus papiloma humano y Chlamydia trachomatis según número de parejas sexuales y tiempo de actividad sexual en estudiantes universitarias en la Región de La Araucanía, Chile. Rev. Chil. infectología [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2019 Jan 10];33:287–92. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27598277.

Quinónez-Calvache EM, Ríos-Chaparro DI, Ramírez JD, Soto-De León SC, Camargo M, Del Río-Ospina L, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis frequency in a cohort of HPV-infected Colombian women. Meyers C, editor. PLoS One [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2019 Jan 10];11:e0147504. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26807957.

Seraceni S, Campisciano G, Contini C, Comar M. HPV genotypes distribution in Chlamydia trachomatis co-infection in a large cohort of women from north-east Italy. J. Med. Microbiol. [Internet]. Microbiology Society; 2016 [cited 2019 Jan 16];65:406–13. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1099/jmm.0.000245

Comar M, Monasta L, Seraceni S, Colli C, Luska V, Morassut S, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis and HPV co-infections in HIV negative men from a multi-ethnic area of Northern Italy at high prevalence of cervical malignancies. J. Med. Virol. [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2019 Jan 10];89:1654–61. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28316071.

Le HHL, Bi X, Ishizaki A, Van Le H, Nguyen TV, Hosaka N, et al. Human papillomavirus infection in male patients with STI-related symptoms in Hanoi, Vietnam. J. Med. Virol. [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2019 Jan 12];88:1059–66. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26519942.

• Janssen KJH, Dirks JAMC, Dukers-Muijrers NHTM, Hoebe CJPA, Wolffs PFG. Review of Chlamydia trachomatis viability methods: assessing the clinical diagnostic impact of NAAT positive results. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Feb 26];18:739–47. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29987959. Recent review on the strengths and limitations of methods used to assess C. trachomatis viability.

Chun S, Shin K, Kim KH, Kim HY, Eo W, Lee JY, et al. The neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio predicts recurrence of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. J. Cancer [Internet]. Ivyspring International Publisher; 2017 [cited 2019 Jan 14];8:2205–11. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28819422.

Cutts F, Franceschi S, Goldie S, Castellsague X, Sanjose S de, Garnett G, et al. Human papillomavirus and HPV vaccines: a review. Bull. World Health Organ. [Internet]. World Health Organization; 2007 [cited 2019 Jan 12];85:719–26. Available from: https://www.scielosp.org/scielo.php?pid=S0042-96862007000900018&script=sci_arttext&tlng=es

Finan RR, Tamim H, Almawi WY. Identification of Chlamydia trachomatis DNA in human papillomavirus (HPV) positive women with normal and abnormal cytology. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. [Internet]. Springer-Verlag; 2002 [cited 2019 Feb 8];266:168–71. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-001-0261-8

Lehmann M, Groh A, Rödel J, Nindl I, Straube E. Detection of Chlamydia trachomatis DNA in cervical samples with regard to infection by human papillomavirus. J. Infect. [Internet]. 1999 [cited 2019 Feb 8];38:12–7. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10090499.

Knowlton AE, Fowler LJ, Patel RK, Wallet SM, Grieshaber SS. Chlamydia induces anchorage independence in 3T3 cells and detrimental cytological defects in an infection model. PLoS One [Internet]. Public Library of Science; 2013 [cited 2016 Feb 9];8:e54022. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0054022

Fang L, Ward MG, Welsh PA, Budgeon LR, Neely EB, Howett MK. Suppression of human papillomavirus gene expression in vitro and in vivo by herpes simplex virus type 2 infection. Virology [Internet]. 2003 [cited 2019 Feb 26];314:147–60. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14517068.

Croy TR, Kuo CC, Wang SP. Comparative susceptibility of eleven mammalian cell lines to infection with trachoma organisms. J. Clin. Microbiol. [Internet]. 1975 [cited 2019 Feb 26];1:434–9. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/809479.

Hough AJ, Rank RG. Induction of arthritis in C57B1/6 mice by chlamydial antigen. Effect of prior immunization or infection. Am. J. Pathol. [Internet]. 1988 [cited 2019 Feb 26];130:163–72. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3337210.

•• Sherchand SP, Ibana JA, Zea AH, Quayle AJ, Aiyar A. The high-risk human papillomavirus E6 oncogene exacerbates the negative effect of tryptophan starvation on the development of Chlamydia trachomatis. PLoS One [Internet]. Public Library of Science; 2016 [cited 2019 Jan 13];11:e0163174. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27658027. The first definitive evidence that HPV E6/E7 expression in host cells can influence progression of the chlamydial developmental cycle.

Ronco L V, Karpova AY, Vidal M, Howley PM. Human papillomavirus 16 E6 oncoprotein binds to interferon regulatory factor-3 and inhibits its transcriptional activity. Genes Dev. [Internet]. 1998 [cited 2019 Feb 26];12:2061–72. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9649509.

Barnard P, McMillan NAJ. The human papillomavirus E7 oncoprotein abrogates signaling mediated by interferon-α. Virology [Internet]. 1999 [cited 2019 Feb 26];259:305–13. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10388655.

Barnard P, Payne E, McMillan NAJ. The human papillomavirus E7 protein is able to inhibit the antiviral and anti-growth functions of interferon-α. Virology [Internet]. 2000 [cited 2019 Feb 26];277:411–9. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11080488.

Evans M, Borysiewicz LK, Evans AS, Rowe M, Jones M, Gileadi U, et al. Antigen processing defects in cervical carcinomas limit the presentation of a CTL epitope from human papillomavirus 16 E6. J. Immunol. [Internet]. 2001 [cited 2019 Feb 26];167:5420–8. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11673561.

Bottley G, Watherston OG, Hiew Y-L, Norrild B, Cook GP, Blair GE. High-risk human papillomavirus E7 expression reduces cell-surface MHC class I molecules and increases susceptibility to natural killer cells. Oncogene [Internet]. 2008 [cited 2019 Feb 26];27:1794–9. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17828295.

Cordano P, Gillan V, Bratlie S, Bouvard V, Banks L, Tommasino M, et al. The E6E7 oncoproteins of cutaneous human papillomavirus type 38 interfere with the interferon pathway. Virology [Internet]. Academic Press; 2008 [cited 2019 Feb 26];377:408–18. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0042682208002924?via%3Dihub

Prantner D, Sikes JD, Hennings L, Savenka AV, Basnakian AG, Nagarajan UM. Interferon regulatory transcription factor 3 protects mice from uterine horn pathology during Chlamydia muridarum genital infection. Infect. Immun. 2011;79:3922–33.

Slade JA, Hall J V, Kintner J, Schoborg R V. The type I interferon receptor is not required for protection in the Chlamydia and HSV-2 murine super-infection model. Pathog. Dis. [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Jan 17];76. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30321322.

Beatty PR, Stephens RS. CD8+ T lymphocyte-mediated lysis of Chlamydia-infected L cells using an endogenous antigen pathway. J. Immunol. [Internet]. 1994 [cited 2019 Feb 26];153:4588–95. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7963531.

Aiyar A, Quayle AJ, Buckner LR, Sherchand SP, Chang TL, Zea AH, et al. Influence of the tryptophan-indole-IFNγ axis on human genital Chlamydia trachomatis infection: role of vaginal co-infections. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. [Internet]. Frontiers Media SA; 2014 [cited 2016 Dec 15];4:72. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24918090.

Wyrick PB, Knight ST. Pre-exposure of infected human endometrial epithelial cells to penicillin in vitro renders Chlamydia trachomatis refractory to azithromycin. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. [Internet]. 2004 [cited 2019 Feb 26];54:79–85. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15163653.

Reveneau N, Crane DD, Fischer E, Caldwell HD. Bactericidal activity of first-choice antibiotics against gamma interferon-induced persistent infection of human epithelial cells by Chlamydia trachomatis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. [Internet]. 2005 [cited 2019 Feb 26];49:1787–93. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.49.5.1787-1793.2005

Phillips-Campbell R, Kintner J, Schoborg RV. Induction of the Chlamydia muridarum stress/persistence response increases azithromycin treatment failure in a murine model of infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014;58:1782–4.

•• Chumduri C, Gurumurthy RK, Zietlow R, Meyer TF. Subversion of host genome integrity by bacterial pathogens. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2019 Feb 27];17:659–73. Available from: http://www.nature.com/articles/nrm.2016.100. A recent elegant review on bacterially induced, mammalial cell genomic instability, including that due to C. trachomatis infection.

Campbell S, Richmond SJ, Yates P. The development of Chlamydia trachomatis inclusions within the host eukaryotic cell during interphase and mitosis. Microbiology [Internet]. 1989 [cited 2019 Feb 26];135:1153–65. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2559942.

Greene W, Zhong G. Inhibition of host cell cytokinesis by Chlamydia trachomatis infection. J. Infect. [Internet]. 2003 [cited 2019 Feb 26];47:45–51. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12850162.

Grieshaber SS, Grieshaber NA, Miller N, Hackstadt T. Chlamydia trachomatis causes centrosomal defects resulting in chromosomal segregation abnormalities. Traffic [Internet]. 2006 [cited 2019 Feb 26];7:940–9. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00439.x

Chumduri C, Gurumurthy RK, Zadora PK, Mi Y, Meyer TF. Chlamydia infection promotes host DNA damage and proliferation but impairs the DNA damage response. Cell Host Microbe [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2019 Feb 26];13:746–58. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23768498.

Song S, Pitot HC, Lambert PF. The human papillomavirus type 16 E6 gene alone is sufficient to induce carcinomas in transgenic animals. J. Virol. [Internet]. American Society for Microbiology (ASM); 1999 [cited 2019 Feb 5];73:5887–93. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10364340.

Duensing S, Duensing A, Crum CP, Mü NK. Human papillomavirus type 16 E7 oncoprotein-induced abnormal centrosome synthesis is an early event in the evolving malignant phenotype 1 [Internet]. Cancer Res. 2001; Available from: http://cancerres.aacrjournals.org/content/61/6/2356.full-text.pdf.

Doxsey S. Re-evaluating centrosome function. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. [Internet]. Nature Publishing Group; 2001 [cited 2019 Jan 15];2:688–98. Available from: http://www.nature.com/articles/35089575

Grieshaber SS, Grieshaber NA, Hackstadt T. Chlamydia trachomatis uses host cell dynein to traffic to the microtubule-organizing center in a p50 dynamitin-independent process. J. Cell Sci. [Internet]. 2003 [cited 2019 Jan 15];116:3793–802. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12902405.

Mital J, Lutter EI, Barger AC, Dooley CA, Hackstadt T. Chlamydia trachomatis inclusion membrane protein CT850 interacts with the dynein light chain DYNLT1 (Tctex1). Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. [Internet]. NIH Public Access; 2015 [cited 2019 Jan 13];462:165–70. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25944661.

• Bordignon V, Di Domenico E, Trento E, D’Agosto G, Cavallo I, Pontone M, et al. How human papillomavirus replication and immune evasion strategies take advantage of the host DNA damage repair machinery. Viruses [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2019 Feb 26];9:390. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29257060. A focused review of how HPV infection promotes host DNA damage as an immune evasion strategy.

Patel S, Chiplunkar S. Host immune responses to cervical cancer. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. [Internet]. 2009 [cited 2019 Feb 26];21:54–9. Available from: https://insights.ovid.com/crossref?an=00001703-200902000-00010

Hawkins RA, Rank RG, Kelly KA. A Chlamydia trachomatis-specific Th2 clone does not provide protection against a genital infection and displays reduced trafficking to the infected genital mucosa. Infect. Immun. [Internet]. 2002 [cited 2019 Feb 27];70:5132–9. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12183563.

Tseng CTK, Rank RG. Role of NK cells in early host response to chlamydial genital infection. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5867–75.

Johansson M, Schön K, Ward M, Lycke N. Genital tract infection with Chlamydia trachomatis fails to induce protective immunity in gamma interferon receptor-deficient mice despite a strong local immunoglobulin A response. Infect. Immun. [Internet]. 1997 [cited 2019 Feb 26];65:1032–44. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9038313.

Hook CE, Matyszak MK, Gaston JSH. Infection of epithelial and dendritic cells by Chlamydia trachomatis results in IL-18 and IL-12 production, leading to interferon-gamma production by human natural killer cells. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. [Internet]. 2005 [cited 2019 Feb 26];45:113–20. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.femsim.2005.02.010

Lee SJ, Cho YS, Cho MC, Shim JH, Lee KA, Ko KK, et al. Both E6 and E7 oncoproteins of human papillomavirus 16 inhibit IL-18-induced IFN-gamma production in human peripheral blood mononuclear and NK cells. J. Immunol. [Internet]. 2001 [cited 2019 Feb 26];167:497–504. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11418688.

Hook CE, Telyatnikova N, Goodall JC, Braud VM, Carmichael AJ, Wills MR, et al. Effects of Chlamydia trachomatis infection on the expression of natural killer (NK) cell ligands and susceptibility to NK cell lysis. Clin. Exp. Immunol. [Internet]. 2004 [cited 2019 Feb 26];138:54–60. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02596.x

Mei B, Du K, Huo Z, Zou Y, Yu P. Discrepant effects of Chlamydia trachomatis infection on MICA expression of HeLa and U373 cells. Infect. Genet. Evol. [Internet]. 2010 [cited 2019 Feb 26];10:740–5. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1567134810001139

Ibana JA, Aiyar A, Quayle AJ, Schust DJ. Modulation of MICA on the surface of Chlamydia trachomatis-infected endocervical epithelial cells promotes NK cell-mediated killing. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2019 Feb 26];65:32–42. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-695X.2012.00930.x

Conrad RD, Liu AH, Wentzensen N, Zhang RR, Dunn ST, Wang SS, et al. Cytologic patterns of cervical adenocarcinomas with emphasis on factors associated with underdiagnosis. Cancer Cytopathol. [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Feb 26];126:950–8. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30351473.

Kiviat NB, Paavonen JA, Brockway J, Critchlow CW, Brunham RC, Stevens CE, et al. Cytologic manifestations of cervical and vaginal infections. I. Epithelial and inflammatory cellular changes. JAMA [Internet]. 1985 [cited 2019 Feb 26];253:989–96. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3968836.

Rank RG, Whittimore J, Bowlin AK, Dessus-Babus S, Wyrick PB. Chlamydiae and polymorphonuclear leukocytes: unlikely allies in the spread of chlamydial infection. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. [Internet]. 2008 [cited 2016 Jan 16];54:104–13. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2925246&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract

Wyrick PB, Knight ST, Paul TR, Rank RG, Barbier CS. Persistent chlamydial envelope antigens in antibiotic-exposed infected cells trigger neutrophil chemotaxis. J. Infect. Dis. [Internet]. 1999 [cited 2019 Feb 26];179:954–66. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10068592.

•• Butin-Israeli V, Bui TM, Wiesolek HL, Mascarenhas L, Lee JJ, Mehl LC, et al. Neutrophil-induced genomic instability impedes resolution of inflammation and wound healing. J. Clin. Invest. [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Feb 26];129:712–26. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30640176. An elegant dissection of neutrophil miRNA-mediated DSB induction in intestinal epithelial cells.

•• McNamee EN. Neutrophil-derived microRNAs put the (DNA) breaks on intestinal mucosal healing. J. Clin. Invest. [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Feb 26];129:499–502. Available from: https://www.jci.org/articles/view/125779. A concise commentary summarizing the findings by Butin-Israeli et al. 2019 and some implications of that work.

Richmond SJ, Stirling P. Localization of chlamydial group antigen in McCoy cell monolayers infected with Chlamydia trachomatis or Chlamydia psittaci. Infect. Immun. [Internet]. 1981 [cited 2019 Feb 26];34:561–70. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7309240.

Karimi ST, Schloemer RH, Wilde Iii CE. Accumulation of chlamydial lipopolysaccharide antigen in the plasma membranes of infected cells. Infect. Immun. [Internet]. 1989 [cited 2018 Jul 11];1780–5. Available from: http://iai.asm.org/content/57/6/1780.full.pdf

Pichon M, Gaymard A, Lebail-Carval K, Frobert E, Beaufils E, Chene G, et al. Vaginal neoplasia induced by an unusual papillomavirus subtype in a woman with inherited chromosomally integrated human herpesvirus type 6A. Gynecol. Obstet. Invest. [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2019 Feb 26];82:307–10. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28380476.

Liu MZ, Hung YP, Huang EC, Howitt BE, Nucci MR, Crum CP. HPV 6-associated HSIL/squamous carcinoma in the anogenital tract. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Feb 26];1. Available from: http://insights.ovid.com/crossref?an=00004347-900000000-99152

Nobre RJ, Herráez-Hernández E, Fei J-W, Langbein L, Kaden S, Gröne H-J, et al. E7 oncoprotein of novel human papillomavirus type 108 lacking the E6 gene induces dysplasia in organotypic keratinocyte cultures. J. Virol. [Internet]. 2009 [cited 2019 Feb 26];83:2907–16. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.02490-08

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Department of Biomedical Sciences, Quillen College of Medicine, as well as by an East Tennessee State University, Center for Infectious Disease, Inflammation and Immunity HIV Pilot Grant. We would also like to thank Dr. Jennifer Hall, Dr. Nicole Borel, and Dr. Russell Hayman for their helpful review of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both authors contributed to the literature review, writing, reading, and approving this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Influences of Hormones and Other Microorganisms on Genital Tract Pathogens

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Slade, J.A., Schoborg, R.V. Human Papilloma Virus and Chlamydia trachomatis: Casual Acquaintances or Partners in Crime?. Curr Clin Micro Rpt 6, 76–87 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40588-019-00117-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40588-019-00117-4