Abstract

Occupational choice is a significant input into workers’ health investments, operating in a manner that can be either health-promoting or health-depreciating. Recent studies have highlighted the potential importance of initial occupational choice on subsequent outcomes pertaining to morbidity. This study is the first to assess the existence and strength of a causal relationship between initial occupational choice at labor entry and subsequent health behaviors and habits. We utilize the Panel Study of Income Dynamics to analyze the effect of first occupation, as identified by industry category and blue collar work, on subsequent health outcomes relating to obesity, alcohol misuse, smoking, and physical activity in 2005. Our findings suggest blue collar work early in life is associated with increased probabilities of obesity, at-risk alcohol consumption, and smoking, and increased physical activity later in life, although effects may be masked by unobserved heterogeneity. The weight of the evidence bearing from various methodologies, which account for non-random unobserved selection, indicates that at least part of this effect is consistent with a causal interpretation. These estimates also underscore the potential durable impact of early labor market experiences on later health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See Viscusi and Aldy (2003) for a review of the literature on the value of a statistical life derived from the tradeoff between wages and job safety.

We note that the chain linking occupational choice at initial labor market entry to subsequent health behaviors into late adulthood has several links, for instance associated with peer influences (from the acquisition of stable behavioral memes to their transmissibility to a subset of occupational entrants), health status (from occupational exposures to diagnosis to changes in health behaviors), health insurance (from coverage to access to shifts in information and incentives), and working conditions and income.

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) reports 4.1 non-fatal workplace injuries and illnesses among 100 equivalent full-time workers in 2008. This national all-industry average masks considerable heterogeneity; the rate in manufacturing industries can vary non-linearly with firm size, with smaller and larger firms displaying lower rates (see for instance Leigh 1989), and the rate can also be higher among state and local government employers. Certain private industries such as crop and animal production, food/beverage and tobacco manufacturing, wood and primary metal manufacturing, hospitals, and nursing and residential care facilities also exhibit higher rates of occupational illness and injury. It should be noted that official data sources tend to underestimate occupational injury and that the reporting errors may systematically differ across industries with small firms more prone to under-reporting. See Leigh et al. (2004) for further discussion on these estimates and the under-counting.

See Cropper (1977) for a formal introduction of occupational choice in Grossman’s human capital framework for the demand for health capital.

In particular, exposure to arsenic may lead to respiratory cancer (Lubin and Fraumeni 2000; Lubin et al. 2000), yet effects on other diseases may be masked by the healthy worker survivor effect (Lubin and Fraumeni 2000; Hertz-Picciotto et al. 2000). Coal miners, hard-rock miners, tunnel workers, concrete-manufacturing workers, and non-mining industrial workers have been shown to be at risk for developing COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) later in life (Boschetto et al. 2006; Govender et al. 2011). Thus, occupational exposure to dusts, chemicals, and gases has been shown to lead to COPD. Hip and knee injuries that occur at work have effects on osteoarthritis later in life. (See Aluoch and Wao 2009 for a comprehensive summary of this research. More information on occupational health can be found in Levy and Wegman 2000.) Many of these studies utilize small sample sizes and are correlational. Moreover, while they are key in identifying the mechanism through which blue collar work may affect subsequent health, they do not focus on the net effect, which is the focus of our study. We thank an anonymous reviewer for further highlighting this important mechanism.

See Health Insurance Coverage in America, 2008, accessed at The Kaiser Family Foundation website: http://facts.kff.org/chartbook.aspx?cb=57.

See Theorell (2000) for a review of this literature.

The direction and magnitude, however, is unknown, depending on the nature of the joint distribution of the observed and unobserved characteristics.

To the extent that learning of job-related hazards may take time, workers may selectively quit their initial jobs when they do learn (see for instance Viscusi and O’Connor 1984), based on their preference for risk-taking and/or tradeoff between risk and wages. This would tend to understate any adverse effects of initial occupation on unhealthy behaviors since the first job may be a “mistake” for some individuals and these individuals are not exposed to their initial occupation for a lengthy period of time. In subsequent analyses we control for both the initial and current occupation to partially tease out such sorting. And, to the extent that the same set of unobservable (for instance, risk and time preference or alternate opportunities in the labor market) determine both sorting into initial occupation and quitting the initial occupation, our estimation strategy (constrained selection models and instrumental variables) would partly account for selective quitting.

We also estimated models based on 1999 outcomes (results available upon request); estimates were similar and conclusions remain unchanged.

This is similar to the standard definition for binge drinking, though binge (or heavy episodic) drinking refers to consuming 5/4 or more drinks for males/females on a single occasion rather than a single day.

See http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/ for more information.

Farmers denote farm owners and are therefore excluded from blue-collar classification. Farm workers are included in the laborer category and thus classified as blue-collar.

A dummy variable is included in models indicating whether a 1-digit occupation code was used instead. This dummy variable will likely be correlated with age.

In our initial specifications, we do not control for mediating factors such as household income and hours worked, which may represent mechanisms through which initial occupation affects health behaviors. Models reported in Table 4 assess the importance of these mediators. We also do not control for health insurance as well as health status and diagnoses such as hypertension, cancer, and other conditions in our main models for two reasons. First, these measures are potentially endogenous to occupation and health behaviors. Second, they represent potential pathways through which occupational choice may impact subsequent health behaviors. We do note however that in supplementary analyses (results available upon request), the inclusion of these covariates does not qualitatively alter our results or conclusions.

Parental education is categorical: (1) grades 0–5, (2) grades 6–8, (3) grades 9–11, (4) grade 12, (5) 12 grades + non-academic training; R.N., (6) some college, no degree; associate’s degree, (7) college baccalaureate degree and no advanced degree mentioned; normal school; RN with 3 years of college, and (8) college, advanced or professional degree; some graduate work.

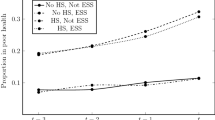

The categories can be ranked in order, without any functional form restrictions on the preference parameters or the utility function. Almost half (48.6 %) of the respondents can be classified in the most risk-averse category, with 31.8 % divided equally among the second and third most risk-averse groups, and 19.6 % comprising the least risk-averse categories. Barsky et al. (1997) provide a detailed analysis of the survey instrument and validate it by showing that it is related to behaviors (insurance, portfolio allocation, migration, risky health behaviors, self-employment) that would be expected to vary with an individual’s propensity to take risks. See PSID documentation for the specific income gamble questions (http://psidonline.isr.umich.edu/data/Documentation/Cbks/Supp/rt.html).

The effect magnitude based on the generated first-occupation variable are smaller (4.7 % points) but still significant at the 5 % level (for a two-tailed test).

The effects of the other covariates are consistent with the literature on obesity; obesity is higher among individuals who are black (relative to all other races), college-educated (though imprecisely estimated), and never-married, and individuals whose parents are low-educated. The coefficients on the indicators of risk tolerance (least risk-averse being the reference category) suggest that more risk-averse individuals have lower probabilities of being obese.

Complete results for the parsimonious specifications for all outcomes can be found in Kelly et al. (2011).

The prevalence of at-risk drinking is higher among males and non-Hispanic whites, and among never-married individuals.

As a validation check, we also estimated models for moderate drinking (results not reported). There were generally no effects of initial occupation on moderate alcohol consumption, which is to be expected given that prior studies have generally found inconsistent effects between moderate alcohol consumption and labor market outcomes and health.

Coefficient estimates for the other covariates are consistent with the literature (Chaloupka and Warner 2000) suggest that the likelihood of being a current smoker is higher among males, non-Hispanic whites, individuals with less than a high school education, those who are single, and those with low maternal education. Individuals with a high tolerance for risk are also more likely to be current smokers.

We find some significant effects for smoking in 1999 (results available upon request).

Studies have indicated that attrition in the PSID does not generally bias results (Fitzgerald et al. 1998; Zabel 1998). In Appendix Table 7, we show results from the baseline model where 2005 PSID longitudinal weights, which take attrition into account, are employed in the regressions. These weights take into account nonresponse and mortality; the reciprocal of the conditional probability that the individual responded given that the individual is alive is the factor used to adjust the weight for differential nonresponse and mortality. The procedure is described in further detail in Gouskova et al. (2008).

As physical activity is a continuous measure of weekly frequency, we are unable to estimate constrained-selection bivariate probit models for this outcome.

Selection effects theoretically can be either negative or positive. For instance, individuals with a high rate of time preference (more present oriented) may be more likely to enter blue-collar occupations and also less likely to invest in their health leading to higher obesity; this would lead to positive selection bias. On the other hand, individuals with a taste for physical activity and manual labor may also be more likely to enter blue-collar occupations but would be less likely to be obese; this would lead to negative selection bias.

Household income is a computed variable, equal to the sum of: Taxable Income of Head and Wife, Transfer Income of Head and Wife, Taxable Income of Other Family Unit Members (OFUMs), Transfer Income of OFUMs, and Social Security Income.

References

Altonji, J. G., Elder, T. E., & Taber, C. (2005). Selection on observable and unobservable variables: Assessing the effectiveness of Catholic schools. Journal of Political Economy, 113(1), 151–184.

Aluoch, M. A., & Wao, H. O. (2009). Risk factors for occupational osteoarthritis: A literature review. AAOHN, 57(7), 283–290.

Bang, K. M., & Kim, J. H. (2001). Prevalence of cigarette smoking by occupation and industry in the United States. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 40, 233–239.

Barsky, R., Juster, T., Kimball, M., & Shapiro, M. (1997). Preference parameters and behavioral heterogeneity: An experimental approach in the health and retirement study. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(2), 537–579.

Berger, M. C., & Leigh, J. P. (1988). The effect of alcohol use on wages. Applied Economics, 20(10), 1343–1351.

Borjas, G. J. (2004). Labor economics. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Boschetto, P., Quintavalle, S., Miotto, D., Lo Cascio, N., Zeni, E., & Mapp, C. E. (2006). Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and occupational exposures. Journal of Occupational Medicine and Toxicology, 1, 11.

Boskin, M. J. (1974). A conditional logit model of occupational choice. Journal of Political Economy, 82(2), 389–398.

Bray, J. W. (2005). Alcohol use, human capital, and wages. Journal of Labor Economics, 23(2), 279–312.

Brown, C. (1980). Equalizing differences in the labor market. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 94(1), 113–134.

Breusch, T., & Pagan, A. (1979). A simple test for heteroscedasticity and random coefficient variation. Econometrica, 47(5), 1287–1294.

Burton, N. W., & Turrell, G. (2000). Occupation, hours worked, and leisure-time physical activity. Preventive Medicine, 31(6), 673–681.

Case, A., & Deaton, A. (2005). Broken down by work and sex: How our health declines. In D. Wise (Ed.), Analyses in the economics of aging. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Cesur, R. (2009). Essays on the aggregate burden of alcohol abuse, Ph.D. Dissertation: Georgia State University.

Chaloupka, F., & Warner, K. (2000). Economics of smoking. In J. Newhouse & A. Culyer (Eds.), Handbook of health economics, volume IB. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Chou, S., Grossman, M., & Saffer, H. (2004). An economic analysis of adult obesity: Results from the behavioral risk factor surveillance system. Journal of Health Economics, 23(3), 565–587.

Colman, G., & Dave D. (2011). Exercise, physical activity, and exertion over the business cycle, National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 17406.

Cropper, M. L. (1977). Health investment in health, and occupational choice. Journal of Political Economy, 85(6), 1273–1294.

Cutler, D., Glaeser, E., & Shapiro, J. (2003). Why have Americans become more obese? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 17(3), 93–118.

Dave, D., & Kaestner, R. (2002). Alcohol taxes and labor market outcomes. Journal of Health Economics, 21(3), 357–371.

Dave, D., & Saffer, H. (2008). Alcohol demand and risk preference. Journal of Economic Psychology, 29(6), 810–831.

Ettner, S. (1996). New evidence on the relationship between income and health. Journal of Health Economics, 15(1), 67–85.

Ewing, R., Schmid, T., Killingsworth, R., Zlot, A., & Raudenbush, S. (2003). Relationship between urban sprawl and physical activity, obesity, and morbidity. American Journal of Health Promotion, 18(1), 47–57.

Fitzgerald, J., Gottschalk, P., & Moffitt, R. (1998). The impact of attrition in the panel study of income dynamics on intergenerational analysis. Journal of Human Resources, 33(2), 300–344.

Fletcher, J. M., & Sindelar, J. L. (2009). Estimating causal effects of early occupational choice on later health: Evidence using the PSID, National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 15256.

Fletcher, J. M., Sindelar, J. L., & Yamaguchi, S. (2009). Cumulative effects of job characteristics on health, National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 15121.

French, M. T., & Zarkin, G. A. (1995). Is moderate alcohol use related to wages? Evidence from four worksites. Journal of Health Economics, 14(3), 319–344.

Gouskova, E., Heeringa, S. G., McGonagle, K., & Schoenim R. F. (2008). Panel study of income dynamics technical report: Revised longitudinal weights 1993–2005. Ann Arbor, MI: Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan. Available at: http://psidonline.isr.umich.edu/data/weights/Long-weights-doc.pdf.

Govender, N., Lalloo, U. G., & Naidoo, R. N. (2011). Occupational exposures and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A hospital based case-control study. Thorax, 66(7), 597–601.

Grossman, M. (2000). The human capital model. In A. J. Culyer & J. P. Newhouse (Eds.), Handbook of health economics (Vol. 1A, pp. 348–408). Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Gueorguieva, R., Sindelar, J. L., Falba, T. A., Fletcher, J. M., Keenan, P., Wu, R., & Gallo, W. T. (2009). The impact of occupation on self-rated health: Cross-sectional and longitudinal evidence from the health and retirement survey. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 10.1093/geronb/gbn006.

Hadley, J. (2003). Sicker and poorer–the consequences of being uninsured: A review of the research on the relationship between health insurance, medical care use, health, work, and income. Medical Care Research Review, 60(2 Suppl), 3S–75S.

Hamilton, V., & Hamilton, B. (1997). Alcohol and earnings: Does drinking yield a wage premium? Canadian Journal of Economics, 30(1), 135–151.

Harford, T. C., & Brooks, S. D. (1992). Cirrhosis mortality and occupation. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 53(5), 463–468.

Hertz-Picciotto, I., Arrighi, H. M., & Hu, S. W. (2000). Does arsenic exposure increase the risk for circulatory disease? American Journal of Epidemiology, 151(2), 174–181.

Howard, M. O., Kivlahan, D., & Walker, R. D. (1997). Cloninger’s tridimensional theory of personality and psychopathology: Applications to substance use disorders. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 58, 48–66.

Kelly, I. R., Dave, D. M., Sindelar, J. L., & Gallo, W. T. (2011). The impact of early occupational choice on health behaviors. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 16803, Cambridge, MA.

Komlos, J., Smith, P., & Bogin, B. (2004). Obesity and the rate of time preference: Is there a connection? Journal of Biosocial Science, 36(2), 209–219.

Kouvonen, A., Vahtera, J., Väänänen, A., De Vogli, R., Heponiemi, T., Elovainio, M., et al. (2009). Relationship between job strain and smoking cessation: The finnish public sector study. Tobacco Control, 18, 108–114.

Lakdawalla, D., & Philipson, T. (2009). The growth of obesity and technological change. Economics and Human Biology, 7(3), 283–293.

Leigh, J. P. (1989). Firm size and occupational injury and illness incidence rates in manufacturing industries. Journal of Community Health, 14(1), 44–52.

Leigh, J. P. (2011). Economic burden of occupational injury and illness in the United States. Milbank Quarterly, 89(4), 728–772.

Leigh, J. P., Marcin, J. P., & Miller, T. R. (2004). An estimate of the U.S. government’s undercount of nonfatal occupational injuries. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 46(1), 10–18.

Levy, B. S., & Wegman, D. H. (Eds.). (2000). Occupational health: Recognizing and preventing work-related disease and injury (4th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Lewbel, A. (2012). Using heteroscedasticity to identify and estimate mismeasured and endogenous regressor models. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics, 30(1), 67–80.

Light, A. (2005). Job mobility and wage growth: Evidence from the NLSY79. Monthly Labor Review, 128(2), 33–39.

Lubin, J. H., & Fraumeni, J. F., Jr. (2000). Re: Does arsenic exposure increase the risk for circulatory disease? American Journal of Epidemiology, 152(3), 290–293.

Lubin, J. H., Pottern, L. M., Stone, B. J., & Fraumeni, J. F., Jr. (2000). Respiratory cancer in a cohort of copper smelter workers: Results from more than 50 years of follow-up. American Journal of Epidemiology, 151(6), 554–565.

Marmot, M. (2001). Income inequality, social environment, and inequalities in health. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 20(1), 156–159.

Marmot, M., & Bobak, N. (2000). Psychosocial and biological mechanisms behind the recent mortality crisis in central and eastern Europe. In G. A. Cornia & R. Paniccia (Eds.), The mortality crisis in transitional economies. UNU/WIDER studies in development economics (pp. 127–148). Oxford, NY: Oxford University Press.

Marmot, M. G., & Smith, G. D. (1997). Socio-economic differentials in health: The contribution of the Whitehall studies. Journal of Health Psychology, 2(3), 283–296.

MacDonald, Z., & Shields, M. A. (2001). The impact of alcohol consumption on occupational attainment in England. Economica, London School of Economics and Political Science, 68(271), 427–453.

McWilliams, J. M., Meara, E., Zaslavsky, A. M., & Ayanian, J. Z. (2007). Health of previously uninsured adults after acquiring medicare coverage. Journal of the American Medical Association, 298(24), 2886–2894.

Mendolia, S. 2012. The impact of husband’s job loss on partners’ mental health, Review of economics of the household, online first 1–18. doi:10.1007/s11150-012-9149-6.

Menza, M., Golbe, L., Cody, R., & Forman, N. (1993). Dopamine-related personality traits. Neurology, 43, 505–598.

Michie, S., & Williams, S. (2003). Reducing work-related psychological ill health and sickness absence: A systematic literature review. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 60, 3–9.

Mokdad, A. H., Ford, E. S., Bowman, B. A., Dietz, W. H., Vinicor, F., Bales, V. S., et al. (2003). Prevalence of obesity, diabetes, and obesity-related health risk factors, 2001. Journal of the American Medical Association, 289(1), 76–79.

Must, A., Spadano, J., Coakley, E. H., Field, A. E., Colditz, G., & Dietz, W. H. (1999). The disease burden associated with overweight and obesity. Journal of the American Medical Association, 282(16), 1523–1529.

Newhouse, J. P. (2004). Consumer-directed health plans and the RAND health insurance experiment. Health Affairs, 23(6), 107–113.

Oreopoulos, P., & von Wachter, T. (2006). Short- and long-term career effects of graduating in a recession: Hysteresis and heterogeneity in the market for college graduates. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 12159.

Philipson, T. (2001). The world-wide growth in obesity: An economic research agenda. Health Economics, 10(1), 1–7.

Powell, L. M., Tauras, J. A., & Ross, H. (2005). The importance of peer effects, cigarette prices and tobacco control policies for youth smoking behavior. Journal of Health Economics, 24(5), 950–968.

Pratt, M., Macera, C. A., & Blanton, C. (1999). Levels of physical activity and inactivity in children and adults in the United States: Current evidence and research issues. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 31(S11), S526–S533.

Rashad, I., Grossman, M., & Chou, S. (2006). The super size of America: An economic estimation of body mass index and obesity in adults. Eastern Economic Journal, 32(1), 133–148.

Rosen, S. (1986). The theory of equalizing differences. In O. Ashenfelter & R. Layard (Eds.), Handbook of labor economics (pp. 641–692). Amsterdam: North Holland.

Saffer, H., & Dave, D. (2005a). Mental Illness and the demand for alcohol cocaine and cigarettes. Economic Inquiry, 43(2), 229–246.

Saffer, H., & Dave, D. (2005). The effect of alcohol consumption on the earnings of older workers. In Bjorn Lindgren & Michael Grossman (Eds.), Advances in health economics and health services research (Vol. 16, pp. 61–90).

Saffer, H., Dave, D., & Grossman, M. (2011). Racial, ethnic, and gender differences in physical activity. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 17413.

Schnall, P. L., Landsbergis, P. A., & Baker, D. (1994). Annual Review of Public Health, 15, 381–411.

Sindelar, J. L., Fletcher, J., Falba, T., Keenan, P., & Gallo, W. T. (2007). Impact of first occupation on health at older ages. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 13715.

Smith, J. (1999). Healthy bodies and thick wallets: The dual relation between health and SES. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 13(2), 145–166.

Smith, P. K., Bogin, B., & Bishai, D. (2005). Are time preference and body mass index associated? Evidence from the national longitudinal survey of youth. Economics and Human Biology, 3(2), 259–270.

Tekin, E. (2004). Employment, wages, and alcohol consumption in Russia. Southern Economic Journal, 71(2), 397–417.

Theorell, T. (2000). Working conditions and health. In: L. Berkman, & L. Kawachi (Eds.). Social epidemiology. New York, NY:Oxford University Press, Inc.

US Department of Health and Human Services. (1996). Physical activity and health: A report of the surgeon general. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Viscusi, W. K., & Aldy, J. E. (2003). The value of a statistical life: A critical review of market estimates throughout the world. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 27(1), 5–76.

Viscusi, W. K., & O’Connor, C. J. (1984). Adaptive responses to chemical labeling: Are workers bayesian decision makers? American Economic Review, 74(5), 942–956.

Zabel, J. (1998). An analysis of attrition in the panel study of income dynamics and the survey of income and program participation with an application to a model of labor market behavior. Journal of Human Resources, 33(2), 479–506.

Zhang, L., & Rashad, I. (2008). Time preference and obesity: The health consequences of discounting the future. Journal of Biosocial Science, 40(1), 97–113.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge funding from the National Institute of Aging (R01 AG027045). Maureen Canavan provided excellent research assistance. The authors acknowledge the use of Panel Study of Income Dynamics, Sensitive Data, produced and distributed by the Institute for Social Research, Survey Research Center, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI (2007).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kelly, I.R., Dave, D.M., Sindelar, J.L. et al. The impact of early occupational choice on health behaviors. Rev Econ Household 12, 737–770 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-012-9166-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-012-9166-5