Abstract

Purpose of Review

This review elaborates the role of malnutrition in PLHIV (people living with HIV) in the context of COVID-19 and emphasis the need of supplementation, dietary intervention, and nutritional counselling in the post-COVID era. One of the most critical challenges among HIV/AIDS patients is malnutrition since it weakens the immune system and increases risk to opportunistic infections. In HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) infection, weight loss is prevalent due to reduced nutritional consumption, malabsorption, abnormal metabolism, and antiretroviral therapy. Sufficient nutrition is required for optimal immune function, as a result, food therapy is now considered an important adjuvant in the treatment of HIV patients.

Recent Findings

Nutritional intervention, such as the use of dietary supplements, can help to prevent nutrient deficiency, lowering the death risk among malnourished HIV population. Immunocompromised individuals are at very high risk for COVID-19 and malnutrition increases the risk of infection by multiple folds. Interventions, such as nutrition education and counselling are important, to improve the condition of HIV Patients by optimising their nutritional status.

Summary

A balanced diet should be one of the most important priorities in preventing PLHIV against the potentially deadly consequences of COVID-19. It is to be ensured that HIV-positive persons continue to get enough and appropriate assistance, such as nutrition and psychological counselling, in the context of COVID-19 infection. The use of telemedicine to maintain nutritional intervention can be beneficial. To meet their nutritional needs and minimise future difficulties, PLHIV infected with COVID-19 should get specialised nutritional education and counselling.

Graphical abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is an infection that targets the immune system, primarily CD4 cells. It further damages CD4 cells, lowering immunity to opportunistic infections including TB, cryptococcal meningitis, bacterial infections, and malignancies like lymphomas and Kaposi’s sarcoma if they go untreated. Major clinical afflictions of HIV include losing weight, fever, swollen lymph nodes, cough, and diarrhoea[1].

Antiretroviral treatment (ART), which consists of one or more medications, is used to treat HIV. ART does not cure HIV, but it does stop the virus from [replicating in the blood, lowering the viral load to undetectable levels. People living with HIV can live healthy, productive lives attributable to antiretroviral therapy (ART). It also acts as a preventative measure, with a 96% reduction in the likelihood of onward transmission. ART should be used on a daily basis throughout the rest of a patient’s life. If the people living with HIV stick to their therapy, they can continue to get safe and effective ART [1].

Nutritional deficiencies can contribute to decreased immunity and elevated risk to opportunistic infections (OIs), both of which could lead to further malnutrition [2]. Antiretroviral drug absorption and tolerance might also benefit from nutrient consumption. A proper diet can help those living with HIV improve their quality of life (QoL). In PLHIV, poor nutrition hastens disease development, increases morbidity, and shortens survival time [3]. Although proper nutrition cannot cure HIV infection, it is necessary to preserve a person’s immune system in order to maintain a healthy level of physical activity and a decent quality of life. Adults living with HIV/AIDS may have lack of appetite, difficulty eating, and poor nutritional absorption. Counselling the patients regarding the importance of nutrition and encouraging them to take small steps to change their diet can have a significant impact on their health. The development of a positive attitude, which often enhances the quality of life for individuals with HIV/AIDS, will be aided by adequate diet [4].

COVID-19 is a contagious disease caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2, a recently discovered coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2). Multiple comorbidities increase the risk of infection and severity of COVID-19, including the risk of death [5]. People with asthma, diabetes, chronic renal disease, chronic lung disease, major cardiovascular problems, obesity, chronic liver disease, and immunocompromised people are at a greater risk of acquiring SARS-CoV-2 infection.

According to current evidence, PLHIV could be affected with COVID-19 and share many of the same characteristics of illness risk and development as HIV-negative individuals. Multimorbidity and old age proved to be significant predictors of severe morbidity and mortality in COVID-19-HIV coinfected patients [6]. People affected with COVID-19 may experience loss of smell and taste and loss of appetite [7]. It may affect their nutritional status and results in malnutrition, both of which can exacerbate the symptoms of HIV further resulting in worsening of the disease condition.

The multimorbidity among PLHIV must be addressed to maintain the security of their ART supply and remain to view PLHIV as a category for which COVID-19 measures are required. Measures should be taken to ensure that HIV-positive people continue to receive adequate and appropriate support, such as nutrition and psychosocial counselling. The use of telemedicine to maintain nutritional intervention can be beneficial. In the post-COVID era, this review will discuss the impact of malnutrition in PLHIV in the context of COVID-19, emphasising the need of supplements, dietary intervention, and nutritional counselling.

Materials and Methods

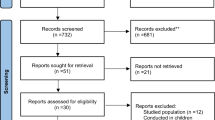

This narrative review is collective evidence gathered, from the following bibliographic databases like PubMed, Google Scholar, and Cochrane, by conducting a thorough search of the literature by using the keywords people living with HIV, nutritional habits, COVID-19, antiretroviral therapy, malnutrition, and SARS-CoV-2. As a criterion for selecting, literature and linguistic filters were used. Only articles written in the English language were evaluated and selected. This narration includes a large quantity of recent data but old literature is also included based relevance. There was no sponsorship from any institutions or groups, and all of the data was freely available to download.

Molecular Basis of Malnutrition Leading to Immunodeficiency Syndrome

The mechanism of immunodeficiency in malnutrition is still unknown, but there are numerous evidences indicating that malnutrition hinders both innate and adaptive immunity. Reduced granulocyte microbicidal activity and innate immune function defects are shown by diminished epithelial barrier function of the gut and skin, fewer circulating dendritic cells, and decreased complement proteins, although leukocyte counts and acute phase response are intact (see Fig. 1). Lymphoid organ atrophy, low soluble IgA expression in tears and saliva, reduced number of circulating B cells, limited delayed-type hypersensitivity responses, lymphocyte hyperresponsiveness to phytohemagglutinin, and a shift from Th1- to Th2-associated cytokines are all indicators of impaired adaptive immune function, even with preserved lymphocyte and immunoglobulin levels in peripheral blood (Fig. 2) [8].

Malnutrition impairs the phagocyte activity and availability of complement components, which has a direct impact on pathogen clearance. This occurs because the complement system can kill bacteria or viruses on its own or since complement receptors on the phagocyte surface mediate pathogen capture. Sakamoto et al. [9] found much reduced amounts of complement, particularly C3, which is the major opsonic component. Furthermore, the capacity of phagocytes to consume and destroy pathogens was decreased [10].

In the development, modulation, and maintenance of innate and acquired immune responses, antigen-presenting cells (APC) play a critical role [11]. A number of researches have shown that nutritional deficiencies reduce the biological activity of several cell types (macrophages, Kupffer cells, and B lymphocytes) [12, 13].

Micronutrient deficits can lead to mental impairment, stunted development, higher mortality, and infection susceptibility. The innate T-cell–mediated immune response and the adaptive antibody response are both affected by their absence. Infections worsen micronutrient deficits by lowering food intake, raising losses, and interfering with utilisation by changing metabolic pathways. Trace elements and antioxidant vitamins (copper, selenium, zinc, vitamins E and C) protect biological tissues from reactive oxygen species, control immune cell activity, and influence cytokine and prostaglandin synthesis. Vitamins B6, B12 folate, E, and C, copper, zinc, iron, and selenium, all encourage a Th1 cytokine-mediated immune response and prevent a transition to an anti-inflammatory Th2 cell-mediated immune response. Vitamins A and D support a Th2-mediated anti-inflammatory cytokine profile and play significant roles in both humoral and cell-mediated antibody responses. Vitamin A deficiency affects both adaptive immunity (infection response) and innate immunity (mucosal epithelial renewal), resulting in a reduced ability to fight extracellular infections. Because of the decreased localised innate immunity and deficiencies in antigen-specific cellular immune response, deficiency of vitamin D is further linked to an elevated susceptibility to infections [14, 15].

Malnutrition causes thymus alterations as a result of protein energy deficit. Apoptosis-induced thymocyte depletion causes significant shrinkage, as well as a reduction in cell proliferation. Acute infections, which are prevalent in malnourished individuals, also damage the thymus’ microenvironment compartment. Deficiencies in vitamins and trace minerals can also cause significant alterations in the thymus. The effects of these alterations can be reversed with the right supplements [16, 17].

Malnutrition and Associated Complications in PLHIV

Malnutrition is one of the major serious issues among HIV/AIDS patients [18]. Malnutrition weakens the body’s immune system, increasing vulnerability to infectious illnesses and therefore increasing the requirement for adequate nutritional supplements in biological system. Malnutrition’s side effects, such as an inability to satisfy nutritional demands by the biological system to act as precursors to various immune pathways, can put patients at increased risk of infection, especially in immunocompromised individuals demonstrating the close link between nutrition and HIV/AIDS. PLHIV who are malnourished exhibit a variety of symptoms, including weakened immune system, weight loss, micronutrient deficiencies, and muscle wasting, and are thus vulnerable to opportunistic infections [19]. Nutrition, obviously, plays a critical part in preserving one's health and immune system, as well as slowing the progression of HIV to AIDS [20].

Negative feedback loops between undernutrition and HIV status exist, with serious consequences for individual, household, and community resilience. Such interactions emerge at the level of the HIV-infected person as well as at the level of impacted families in terms of clinical progression of disease, quality of life, and economic and nutritional consequences. Individually, a lack of suitable meals and the direct influence of HIV on altered metabolic processes in nutrition absorption, storage, and utilisation can lead to compromised immunisation [21]. Weight loss is caused by a lack of food intake and/or malabsorption. The catabolic nature of HIV infection is aggravated by this. Weight loss is an independent predictor for AIDS-related mortality, and HIV-related wasting typically continues despite the administration of antiretroviral therapy (ART) [22].

Furthermore, malnutrition increases the incidence of insulin resistance and cardiovascular disease in persons living with HIV after taking antiretroviral treatment as a result of HIV infection (ART). This is also something to be concerned about [20].

According to Thapa R et al.’s [23] study in Kathmandu, one out of every five people living with HIV is malnourished. Nutritional status was discovered to have a favourable relationship with QoL. Nutritional assistance should be a key component of HIV and AIDS response, with increased emphasis on nutritional advice, support, and encouragement for clients.

Malnutrition, whether caused by any underlying pathology or not, needs careful nutritional management. This is due to the fact that severe malnutrition is linked to metabolic anomalies, the most notable of which is hypophosphatemia that is frequently accompanied by a disturbed sodium/potassium balance and oedema. Low plasma phosphate has been found to be prevalent in impoverished Africans commencing ART and to be an independent risk factor for early death [24]. Asymptomatic HIV infection raises basal energy demands by 10% to 30% in individuals having opportunistic infections, whereas intestinal malabsorption, which also is common in HIV, lowers nutritional intake via meals [25].

Patients with weight loss and wasting due to dietary and metabolic abnormalities may have a persistent inflammatory condition. Inflammatory and other immune reactions affect nutritional status by sequestering minerals (such as zinc and Iron), impairing absorption, increasing loss of nutrient, or changing nutrient use [26].

Risk of COVID-19 Among PLHIV

The concern that PLHIV are more likely to have severe COVID-19 illness derives from the notion that PLHIV are immunocompromised. Infection with HIV is linked to unusual T-cell and humoral immune responses, leaving patients more vulnerable to a wide range of illnesses [27].

People living with HIV who have an elevated viral load have a lower CD4 cell count and advanced illness, and those who are not on antiretroviral treatment may be at risk [6]. As they survive longer on antiretroviral therapy, many PLHIV will acquire chronic diseases linked to severe COVID-19. Recent research (2021) suggests that PLHIV are not only at a higher risk of dying from COVID-19, but also of getting SARS-CoV-2 infection than persons who do not have HIV [28].

Given the global prevalence of PLHIV, there are almost definitely more persons who are coinfected with COVID-19 and HIV than the limited data reveals.

Malnutrition in PLHIV Amidst COVID-19 Pandemic

Because of the pandemic, food insecurity has grown in several countries [29]. Food insecurity is described as restricted or unpredictable accessibility to enough, nutritious food for a healthy and active life [30]. Due to difficulties in obtaining basic food necessities, the individuals affected with HIV have been skipping meals or going hungry.

The outcomes of a study [31] paved light into how PLHIV deal with their food security issues. Instead of going hungry, PLHIV will reduce the quantity of meals or the amount of rations to conserve food for another mealtime. Although it may appear counterintuitive that PLHIV were more likely than non-PLHIV to report reducing the size of servings and numbers of ration while the opposite was true for reporting hunger, it is feasible to lower food portions without raising hunger [32]. However, skipping meals has negative consequences since it causes the metabolism to slow down, resulting in gaining weight over time.

Nutritional balance is critical for improved health outcomes during the course of and recovery from any illness [33]. As a result, malnutrition is likely to have a negative impact on the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) prognosis and hence requires specific care. The COVID-19 pandemic’s immediate nutritional danger is an increased risk of malnutrition as a result of the economic consequences of social isolation, partial or full lockdowns, and quarantining. Many families have lost earnings and/or additional food sources, such as school lunches for children, as a result of the economic downturn. Despite the fact that the causes of malnutrition are numerous, government-imposed shutdowns and quarantines have caused considerable changes in the food industry and dietary practices [34].

COVID-19 appears to have a more direct effect on malnutrition. Malnutrition has been discovered to be more frequent in older COVID-19 patients with severe disease. COVID-19 or its side effects could be causing malnutrition or other physiological processes, according to this research. Malnutrition further weakens the immune system, lengthens hospital stays, increases mortality, and raises the chances of an unexpected readmission [35]. In addition, both chronic and acute malnutrition increase the likelihood of viral and bacterial infection, as well as the severity of the infection [36]. As a result, in all illnesses, including severe COVID-19, a malnourished patient is likely to have a poorer prognosis than a patient who is not malnourished.

Dietary Practices and Preferences Among People Living with HIV

In terms of nutritional variables, studies conducted in underdeveloped countries found that more than half of HIV patients had a poor dietary variety in around 59% of PLHIV [37]. Poor dietary habits and a low level of food security in the families of PLHIV may be one of the reasons for inadequate dietary variety. People in underdeveloped nations eat a lot of starchy staples, which are monotonous, high in calories, and low in micronutrients [19].

Two-thirds of the individuals consume little variety in their meals on a daily or weekly basis, according to a study conducted by Omwanda VA et al. [38] (2020) at Kisii County, exploring the dietary practices and nutrition status of people living with HIV. Their meals consisted mostly of cereals, eggs, fruits, dark green leafy vegetables, and dairy items, with very little beans, organ meats, or meats. The research population’s nutritional state may represent the dietary shift, predisposing PLHIV to cardio-metabolic risk factors. These findings underscore the need of bolstering community nutrition programs in addition to nutrition education in order to increase access to and availability of inexpensive, diverse, and sustained healthy meals for PLHIV.

Dibari et al., (2012) in Kenya, postulated that soft textures and delicate, natural flavours, such as those found in oatmeal, cooked sweet potatoes, or parboiled veggies, were recognised as preferences of patients. Regardless of their health issues, all participants showed a preference for modest quantities of soft, liquid, and semiliquid foods which could be taken at different times throughout the day. It was further postulated that strong flavours are despised and that HIV-related health issues have an impact on food consumption [39].

Spices, fat, sugar, and salt are rarely used, and meals with rough textures and strong smells are despised. Surprisingly, all subjects, including those with mouth ulcers, consumed sour flavours. The idea that sour meals and drinks aid to restore health was connected to the intake of sour flavours. Other research has found that cultural attitudes and food preferences are major predictors of eating habits [40], emphasising the need of taking cultural factors into account when creating nutritional supplements.

Health challenges including mouth sores, diarrhoea and TB as well as cultural beliefs has an important role in determining food preferences of people living with HIV according to a study. It also emphasises the need of taking PLHIV dietary choices, into account additionally, health problems, and food insecurity in the home when developing nutritional supplements. A combination of quantitative and qualitative data collection techniques should be utilised to enhance the nutritional supplement and constantly improve the organoleptic characteristics of the product towards the taste and requirements of PLHIV [41].

Nutritional Status and Associated Factors

A recent finding has stated that the nutritional condition of PLHIV and the variables that are strongly linked to BMI. Nutrition and HIV are intimately linked and mutually beneficial. Micronutrient deficiencies, whether subclinical or severe, diminish the circulating numbers and functional ability of important proteins and immune cells, comprising innate immunity and adaptive immunity factors like T- and B-lymphocyte activities. Micronutrient deficits, such as those in essential fatty acids, zinc, vitamin A, and folate, can result in mucosal lesions or a loss of mucosal integrity, raising the infection risk [15].

A study (2020) conducted among people living with HIV in a Kathmandu hospital-based antiretroviral treatment centre [19] revealed that the nutritional status (BMI score) of persons living with HIV is determined by a variety of variables, including sociodemographic traits, clinical conditions related to HIV, and eating habits. Age, ART treatment duration, haemoglobin level, being married, being male, having a business as a profession, and smoking were all identified as possible variables that impacted the BMI score in the study.

Obesity has been a growing issue among people living with HIV, which is one of a significant risk factor for non-communicable illnesses (NCDs). As a result, it is critical to include NCD screening into HIV treatment and care services as soon as possible, before any more complications emerge. Efforts should be made to promote PLHIV to eat a variety of foods and to make them quit the habit of smoking if applicable.

Role of Antiretroviral Therapy in Nutritional Status

One of the most noteworthy findings concerning the relationship between ART and nutritional status is that starting ART typically results in the reversal of HIV-related symptoms including malnutrition and weight loss (including muscle mass). Nutritional status is enhanced by increased hunger, improved food intake, and a lower viral load. This improvement has been linked to a decrease in HIV-related morbidity and death [42]. In the past decade, significant progress has been made in extending HIV-infected African people’s access to antiretroviral treatment (ART). High death rate in the first few months of ART, on the other hand, remains a serious worry [43, 44]. Lower CD4 counts, advanced WHO disease stages, opportunistic infections like tuberculosis (TB), and malnutrition, as shown by a low BMI, are all consistent risk factors for early mortality. Individuals who are HIV-positive and on antiretroviral treatment may have antiretroviral medication side effects such as nausea and sleeplessness, which can have a detrimental influence on nutrient status. Poor nutritional status can worsen these side effects, which can be exacerbated in part by increased medication toxicity [45]. Several HIV-specific drugs, particularly nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, have been shown to impede mitochondrial DNA replication and produce vomiting and diarrhoea, leading to micronutrient loss [46].

It appears that certain side effects are linked to specific medications. These side effects have the potential to have significant consequences in terms of adherence to ART, increased risk of chronic illnesses such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes, and lowered quality of life. These metabolic consequences not only have an influence on PLHIV’s health and well-being, but they may also demand switching to a different ART regimen [42]. PLHIV should be frequently informed about antiretroviral drug interactions with food and nutrition, as well as how to handle nutritional concerns to minimise their likelihood of inadequate food availability. They must be taught that antiretrovirals should not be administered on an empty stomach. Malnutrition is a risk for PLHIV on antiretroviral treatment due to a lack of appetite, food consumption, nutrient losses, metabolic alterations, and elevated macro and micronutrient needs [47].

COVID-19 Infection and Nutritional Status

Since COVID-19 is characterised by an inflammatory condition that leads to decreased consumption of food and greater muscle catabolism, malnutrition is a serious concern for COVID-19 patients, making malnutrition prevention and nutritional treatment critical parts of care [48]. Malnourishment during COVID-19 infection is caused by an increment in energy expenditure due to ventilatory effort during a severe respiratory infection, which results in inflammation and hyper catabolism, as well as a very low food intake due to a variety of factors including respiratory discomfort, infection-related anorexia, ageusia, anosmia, and digestive symptoms (diarrhoea, abdominal pain, or vomiting) [49].

ACE2, the receptor required for SARS-CoV-2 entrance into host cells, is found in a wide range of gastrointestinal cells, including those of the intestinal epithelium. As a result, SARS-CoV-2 infection may impact the digestive tract, resulting in gastrointestinal problems and a reduction in patients’ nutritional status [50]. The National COVID-19 Cohort Collaborative in the USA looked at COVID-19 cases up until February 2021 and discovered that patients with HIV had a 32% higher chance of being admitted to hospital and an 86 percent higher risk of needing mechanical ventilation [50].

Patients who are most prone to present with malnutrition have poor COVID-19 outcomes (such as PLHIV). Maintaining nutrition status and treating or preventing malnutrition has the ability to lessen problems and unfavourable consequences in nutritionally vulnerable patients and may develop COVID-19 in the future. Hence, persons who are likely to be affected of severe COVID-19 benefit from healthy diet [51].

Like any acute scenario of metabolic aggressiveness, nutritional evaluation, and early dietary care of people with COVID-19 should be included in the entire therapeutic plan. Nutrition may help to modulate some of the key outcomes of COVID-19 infection, such as the pro-inflammatory cytokine storm [51]. The risk of COVID-19 problems does not rise when HIV/AIDS is effectively treated with adequate medication. People living with HIV/AIDS across many regions of the world, however, get sub-standard care and are more likely to develop serious consequences. There is proof indicating that maintaining food and nutritional security for everyone but, especially for persons living with HIV/AIDS, boosts their immune and increases their resilience to other infections. As a result, one of the most important goals in protecting people living with HIV/AIDS from the possibly fatal implications of COVID-19 should be good diet [46].

Supplementation and Dietary Interventions in PLHIV

For optimum immunological function, sufficient nutrition is essential. As a result, dietary therapy is recognised as an essential adjuvant in the therapeutic management of HIV patients [52]. It is thought that obtaining and preserving optimum nutrition can enhance a person’s immune system function, lower the occurrence of HIV-related complications, halt the course of HIV infection, improve life quality, and, eventually, reduce death related to HIV (Fig. 3) [53].ARVs, coinfection treatment, dietary counselling, pharmacological treatments for boosting anabolism or appetite, and nutritional supplementations are all options for improving nutritional results.

The World Health Organization encourages appropriate micronutrient consumptions at dietary reference intakes (DRIs) levels in the diet. It implies that a varied, high-micronutrient diet is more likely to help patients. Patients with HIV, especially those who have poor eating habits or in poverty are likely to be benefitted from taking a multivitamin, trace element, and mineral that provides micronutrients at levels of DRI on a regular basis [54].

Oral nutritional supplements were well tolerated and resulted in body weight gain in HIV-infected individuals, according to an interventional randomised prospective study. CD4 count is increased by a supplement containing peptides and n-3 fatty acids [55]. A research in impoverished African adults starting ART disclosed that supplementing with high-dose vitamins and minerals in a lipid-based nutritional supplement (LNS) had no effect on mortality or clinical SAEs, when compared to LNS alone, although it did increase CD4 count. The high-level supplementation with electrolytes is not suggested for everyone because to the greater incidence of elevated blood potassium and phosphate levels, adding micronutrient supplementation to ART may provide therapeutic advantages in these patients [56].

Micro-nutrient supplements substantially enhanced CD4 count amongst PLHIV in a study (2006) conducted in USA [57], and macronutrient supplementation has been found to have significant positive effects on antiretroviral medication adherence, CD4 counts, and weight gain among HIV-infected adults in Kenya, Haiti, Zambia, and Malawi [57,58,59,60,61]. Food assistance programmes (raising total calories) are frequently necessary in food insecure contexts in addition to nutrition support (rising particular micronutrients) to maximise health outcomes in PLHIV [58].

A dietary intervention for patients in many situations is the medical nutrition therapy (MNT) based on evidence and advice for improving nutrition, malnutrition and nutritional testing, research, intervention, assessment, and monitoring nutritional rehabilitation. Dietitians or nutritionists with communication abilities who can educate patients on food planning and daily physical exercise perform these activities. When MNT is coupled with medical therapy given by healthcare teams, it can enhance the health status of patients with a variety of illnesses, [62] another study found that MNT was helpful in lowering blood lipid profiles in PLHIV by changing eating patterns [63]. Furthermore, research found that nutritional intervention through food supplements can help avoid nutrient insufficiency, lowering the death rate in PLHIV owing to malnutrition.

A recent study (2012) [64] shown that increasing the quantity of calcium and other mineral-rich foods reduced the risk of bone density loss. However, among PLHIV, there is still no research or suggested regimens for the consumption of calcium, vitamin D, magnesium, and phosphorus-rich foods, all of which are helpful to bone health. Good diet and nutritional therapies may improve the lifespan and quality of life, management of symptoms, medication and other therapy effectiveness, and the resistance of HIV patient to infections and other disease consequences [65].

Supplementations and Dietary Interventions in COVID-19

Looking at the present COVID-19 pandemic, which has no efficient prophylactic and therapeutic treatment, a strong immune system is amongst the most critical weapons. A variety of trace elements and vitamins are required for the immune system to operate properly (Fig. 4). Additionally, intake of these has been proven to improve immunity in viral diseases [14].

Vitamins A, B6, B12, C, D, E, and folate, as well as trace minerals like selenium, copper, zinc, and magnesium, promote both the innate and adaptive immune systems in crucial and complementary ways (Table 1). Micronutrient deficiencies or inadequate status have been shown to have a deleterious impact on immune function and infection resistance. The roles of vitamins D and C in immunity are especially well-known [66, 67].

Due to unique effects on lung and liver storage brought on by inflammation and reduced renal function, vitamin A deficit may arise during COVID-19, and supplements may be required to restore appropriate status. The negative effects of COVID-19 treatments and SARS-CoV-2 on the angiotensin system may both be mitigated by vitamin A supplementations [68].

Vitamin B6 and B12 may be used to treat SARS-CoV-2 infection or to prevent or lessen COVID-19 symptoms in addition to helping to develop and maintain a healthy immune system [70].

Vitamin C has an impact on various elements of immunity, including adaptive and innate immune cell proliferation and function, epithelial barrier function, adaptive and innate immune cell proliferation and function, phagocytosis and microbial death, white blood cell migration to infection sites, and antibody formation [67].

Vitamin D receptors regulate the behaviour of many immune cells after ligand binding, and as a result, vitamin D has a significant impact on immunity. Moreover, vitamin D metabolites seem to govern the synthesis of specific antimicrobial proteins that actively destroy germs, suggesting that they may aid in the prevention of infection, particularly in the lungs [76, 77]. Furthermore, vitamin D has been hypothesised to have antiviral, cellular proliferation, anti-inflammatory effect, gene transcription, and regulation of innate and adaptive immunity. The role of vitamin D in covid related comorbidities is discussed in Kumar et al. (2021). Vitamin D deficiency was correlated with lengthier hospital stay, ICU admissions, etc. [78]. Evidence suggests that supplementation with vitamin D3 may decrease the susceptibility or improve recovery from infections such as influenza, recurrent pneumonia, and tuberculosis [79].

Vitamin E appears to play a role in respiratory tract infections, according to clinical findings. Daily supplementation with 200 IU vitamin E for 1 year decreased the risk of upper respiratory tract infections, but did not lower respiratory tract infections, in a randomised controlled study of 617 nursing home patients [80]. In the face of decrease related to age, vitamin E improves T-cell–mediated immunological activity[81]. Supplementation with vitamin E increased neutrophil chemotaxis and phagocytosis, natural killer cell activity, and mitogen-induced lymphocyte proliferation in older individuals in one trial. Vitamin E supplementation boosted T-cell–mediated immunity in another research, as indicated by higher antibody production against the hepatitis B virus and tetanus vaccinations [82].

Finally, even minor deficiency of zinc might have an effect on immunity. In both the adaptive and innate immune systems, zinc is required for cell maintenance and development. Zinc deficiency impairs lymphocyte production, activation, and maturation, disrupts cytokine-mediated intercellular communication, and reduces innate host defence [83]; by lowering viral load and bosting COVID-19 patient’s immunity, zinc consumption offers an extra line of defence against the illness zinc deficiency which causes increased diarrhoeal and respiratory morbidity, especially in children [84].

Because of its anti-inflammatory properties, selenium is vital to the immune system. In 17 cities outside of Hubei (China), Zhang et al. (2020) discovered a link between a greater recovery rate from COVID-19 infection and appropriate selenium status [85]. The demand for oxygen and critical support in COVID-19 patients was decreased by treatment with selenium, magnesium, and vitamin B12. Exogenous variables that affect gut microbiota, such as drugs, nutrition, or chemical exposure, may trigger lung inflammation via the stated axis, raising the morbidity of fibrosis or pneumonia, which are clinical consequences of COVID-19. In light of this, it has recently been proposed that probiotics can protect against viral infections on three levels: (a) strengthening the innate immune response in the gut, (b) reducing gut permeability, and (c) controlling the acquired immunological response [86].

Probiotics could be offered as a potential strategy to incorporate in the nutritional treatment of COVID-19 patients based on these thoughts. Thus, Renzo et al. (2020) proposed the possible therapeutic application of anti-inflammatory probiotics such Lactobacillus rhamnosus and Bifidobacterium lactis, as well as prebiotics, for restoring innate and adaptive immunity (Table 2) [87]

A well-balanced and diversified diet would be ideal for obtaining intake of all of these nutrients in an optimal amount, but this may be difficult for the general public to achieve. Nutritional deficiencies and impairments are prevalent, as is commonly accepted [94]. The dietary plan should be emphasised especially for those who are immunocompromised, such as PLHIV.

Nutritional Education and Counselling in PLHIV

Nutritional education has a strong link to improving nutritional knowledge and behaviour. Nutrition intervention, delivered through nutrition counselling and education, as part of nutrition care, has the potential to improve PLHIV nutrition knowledge and behaviour. Nutrition counselling and education should be offered to encourage the development of appropriate nutrition habits and assist PLHIV in dealing with nutrition-related issues. Continuous education is an excellent approach for progressively providing services to PLHIV in line with their requirements, and it may be sustained. Since PLHIV are immunocompromised, the education and counselling about nutritional food may come in help for long run. As a result, this should be applied right away before they develop nutritional issues [95]. Unique treatment plans can be organised to attain optimal health through a collaborative and supportive approach between counsellor and client in enhancing nutrition, physical activities, and diet in which the client’s specific targets are accepted. Interventions in health promotion, such as nutrition counselling and education, are important, in order to improve the condition of PLHIV by optimising their nutritional status [96].Nutrition evaluation, nutrition teaching and counselling, micronutrient supplementation, food assistance and actions to enhance family food availability are all part of the nutrition intervention program for PLHIV [97].

Nutritional counselling is an integral part of antiretroviral therapy because poor food security can expedite the course of AIDS-related diseases and decrease adherence and responsiveness to antiretroviral medication. Food security issues for PLHIV are a worldwide problem; thus, nutrition and food security counselling should be included in PLHIV treatment. Individual nutritional counselling was found to be useful in modifying eating habits in HIV-positive individuals. They were also beneficial in improving these individuals’ nutritional condition (weight and BMI). Interventions aimed at changing dietary habits are critical, and they may aid in the prevention of HIV's rapid progress [98].

Nutritional Counselling in PLHIV in the Post-COVID Period

Nutritional assessment and adequate nutritional therapy should be a vital part of holistic patient care for persons, who have or have had COVID-19 disease, since malnutrition left untreated can lengthen hospital stays, result in readmissions, and delay recovery. As a result of their experience with food hardship, PLHIV may be better equipped to handle food insecurity amidst the pandemic than those who are not HIV positive [99]. Nutritional education and counselling should be specially provided to PLHIV affected with COVID-19 to fulfil their nutritional needs and to avoid any future complications.

To help patients manage with nutritional difficulties during and after a COVID-19 infection, a variety of methods may be necessary. This includes ensuring if they are maintaining a balanced diet or not, enquiring are they getting enough vitamins and minerals, or do they need to supplements. Vitamin D consumption may be of significant concern if they are shielding and spending little time outside [100]. If they are recuperating from an illness, have muscle wasting, or are feeling weak, they should pay extra attention to their protein consumption [101]. Taking care of their capacity to obtain the nutrition they require and assure social support if necessary. When using food-based tactics to enhance dietary intake, it’s important to make sure you’re getting enough protein, vitamins, and minerals [102].

It's critical to address the COVID-19 patient’s unique dietary requirements. Given the variety of nutritional issues and challenges that self-isolating/shielding patients face, a sensible approach to the use of ONS should be considered, including the patient’s or caregiver’s ability to consume adequate amounts of essential nutrients and adapt the diet to promote recovery and prevent admission or readmission to the hospital, as well as other malnutrition-related consequences like infections, falls, and pressure ulcers [103].

PLHIV Food and Nutrition Assistance Adjustments in the Context of COVID-19

COVID-19’s health, social, and economic effects may limit the availability of nutritionally appropriate and safe foods, as well as people’s ability to obtain food in socially acceptable methods, including PLWH. According to statistics, the use of food banks is on the rise [104]. Food access and availability are particularly sensitive to the effects of the COVID-19 outbreak at the community level, owing to transportation, distribution, and delivery challenges.

Malnourished HIV-positive persons should continue to be prioritised over blanket distribution, protective rations, or family assistance. The use of specialised nutrient foods (SNF] for the treatment and the prevention of acute malnutrition among PLHIV should be prioritised globally. When possible, the use of inexpensive and secure cash-based transfers (CBT) should be considered for household rations under care and treatment, mitigating safety nets, and HIV-sensitive social protection schemes based on market access and availability of nutritious meals in the market.

Consider bringing food and nutrition assistance closer to HIV patients, perhaps at the community level, to reduce needless interaction between potential carers and PLHIV clients and health staff/lay-counsellors and to alleviate crowding at health facilities. Ensure that people living with HIV continue to receive enough and appropriate support, such as nutrition and psychosocial counselling [105].

To improve the nation’s preparation, significant planning is required at the national level, including the design of policies to support the production, distribution, and accessibility of this food basket to various groups. The use of telemedicine to maintain nutritional intervention can minimise the negative changes in eating habits and physical activity patterns, preventing a significant gain in body weight[106].

Conclusion

HIV has been found to have a deleterious impact on nutritional health by enhancing energy demands, lowering intake of food, and reducing nutrient absorption and metabolism. Cultural attitudes and food preferences are significant indicators of eating behaviours. Hence, it is important to take cultural aspects into account when developing nutritional supplements.

Malnutrition weakens the body’s immune system, increasing vulnerability to infectious illnesses and therefore increasing nutritional requirements. HIV infection leads to malnutrition, which weakens the body’s immune system and progresses to AIDS in the absence of appropriate diet and treatment. Optimal nutrition improves immune function, reduces the frequency of HIV-related issues, delays the course of HIV infection, improves quality of life, and, lastly, reduces death related to HIV. Individuals who are HIV-positive and on antiretroviral treatment may have side effects of antiretroviral drugs such as nausea and sleeplessness, which can have a detrimental influence on nutrient status. Hence, proper nutritional counselling and education are to be provided to them.

SARS-CoV-2 infection may impact the digestive tract, resulting in gastrointestinal problems and a reduction in patients’ nutritional status. Maintaining nutritional status and treating or preventing malnutrition has the ability to lessen problems and unfavourable outcomes in PLHIV. Hence, persons at the risk of severe COVID-19 benefit from healthy diet. One of the most important goals in protecting people living with HIV/AIDS from the possibly fatal implications of COVID-19 should be good diet. Supplementations can be added to the drug regimens if needed. It is important to maintain a healthy immune system in those individuals. Studies should be conducted further to fill the knowledge gaps in the field of PLHIV affected with COVID-19. Prophylaxis and pharmacotherapy are to be fixed,and the existing guidelines are to be revised according to the newly emerged havoc, COVID-19.

Due to transportation, distribution, and delivery constraints, food access and availability are particularly vulnerable to the consequences of the COVID-19 outbreak at the community level. It is vital to ascertain that HIV-positive people continue to receive appropriate and adequate support, such as nutrition and psychosocial counselling. The use of telemedicine to maintain nutritional intervention can be beneficial.

References

HIV/AIDS. Who.int. 2022 Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/hiv-aids#tab=tab_1. Accessed 27 June 2022.

Malnutrition Who.int. 2022 Available from: https://www.who.int/healthtopics/malnutrition#tab=tab_1. Accessed 27 June 2022.

Puri S, Mathew M, Anand D. Assessment of quality of life of HIV-positive people receiving art An Indian perspective. Indian J Community Med. 2012;37(3):165–9.

HIV/AIDS a guide for nutritional support [Internet]. 2022 Available from: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/hivaids-guide-nutritional-care-and-support?gclid=Cj0KCQjwuaiXBhCCARIsAKZLt3k33gBdHAgt_zxK6bx7ZVpDRFILpxtdjMrs8mmuv8MqGayCtdiMhsoaAsruEALw_wcB. Accessed 27 June 2022.

Gallo Marin B, Aghagoli G, Lavine K, Yang L, Siff EJ, Chiang SS, et al. Predictors of COVID-19 severity: a literature review. Rev Med Virol. 2021;31(1):1–10.

Mirzaei H, McFarland W, Karamouzian M, Sharifi H. COVID-19 among people living with HIV: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2021;25(1):85–92.

COVID-19 basics - Harvard Health [Internet]. Harvard Health. 2022 Available from: https://www.health.harvard.edu/diseases-and-conditions/covid-19-basics. Accessed 27 June 2022.

Rytter MJH, Kolte L, Briend A, Friis H, Christensen VB. The immune system in children with malnutrition—a systematic review. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e105017.

Sakamoto M, Fujisawa Y, Nishioka K. physiologic role of the complement system in host defense, disease, and malnutrition. Nutrition. 1998;14(4):391–8.

Chandra R. Nutrition and the immune system from birth to old age. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2002;56(S3):S73-6.

Mellman I, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells: specialized and regulated antigen processing machines. Cell. 2001. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00449-4.

Petro TM, Schwartz KM, Chen SSA. Production of IL2 and IL3 in syngeneic mixed lymphocyte reactions of BALB/C mice are elevated during a period of moderate dietary protein deficiency. Immunol Invest. 1994;23(2):143–52.

Redmond HP, Shou J, Kelly CJ, Schreiber S, Miller E, Leon P, et al. Immunosuppressive mechanisms in protein-calorie malnutrition. Surgery. 1991;110(2):311–7.

Wintergerst ES, Maggini S, Hornig DH. Contribution of selected vitamins and trace elements to immune function. Ann Nutr Metab. 2007;51(4):301–23.

Cunningham-Rundles S, McNeeley DF, Moon A. Mechanisms of nutrient modulation of the immune response. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115(6):1119–28.

Savino W, Dardenne M, Velloso LA, Dayse Silva-Barbosa S. The thymus is a common target in malnutrition and infection. Br J Nutr. 2007;98(S1):S11-6.

Savino W, Dardenne M. Nutritional imbalances and infections affect the thymus: consequences on T-cell-mediated immune responses. Proc Nutr Soc. 2010;69(4):636–43.

Norman K, Pichard C, Lochs H, Pirlich M. Prognostic impact of disease-related malnutrition. Clin Nutr. 2008;27(1):5–15.

Khatri S, Amatya A, Shrestha B. Nutritional status and the associated factors among people living with HIV: an evidence from cross-sectional survey in hospital based antiretroviral therapy site in Kathmandu Nepal. BMC Nutr. 2020;6(1):22.

Ivers LC, Cullen KA, Freedberg KA, Block S, Coates J, Webb P. HIV/AIDS, Undernutrition, and Food Insecurity. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(7):1096–102.

Katona P, Katona-Apte J. The interaction between nutrition and infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46(10):1582–8.

Tang AM, Forrester J, Spiegelman D, Knox TA, Tchetgen E, Gorbach SL. Weight loss and survival in HIV-positive patients in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;31(2):230–6.

Thapa R, Amatya A, Pahari DP, Bam K, Newman MS. Nutritional status and its association with quality of life among people living with HIV attending public anti-retroviral therapy sites of Kathmandu Valley Nepal. AIDS Res Ther. 2015;12(1):14.

Heimburger DC, Koethe JR, Nyirenda C, Bosire C, Chiasera JM, Blevins M, et al. Serum phosphate predicts early mortality in adults starting antiretroviral therapy in Lusaka, Zambia: A Prospective Cohort Study. PLoS One. 2010;5(5):e10687.

Hsu J, Pencharz P, Macallan D, Tomkins A. Macronutrients and HIV/AIDS: a review of current evidence. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005.

Semba RD, Tang AM. Micronutrients and the pathogenesis of human immunodeficiency virus infection. Br J Nutr. 1999;81(3):181–9.

Chang CC, Crane M, Zhou J, Mina M, Post JJ, Cameron BA, et al. HIV and co-infections. Immunol Rev. 2013;254(1):114–42.

Ssentongo P, Heilbrunn ES, Ssentongo AE, Advani S, Chinchilli VM, Nunez JJ, et al. Epidemiology and outcomes of COVID-19 in HIV-infected individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):6283.

The Lancet HIV. The syndemic threat of food insecurity and HIV. Lancet HIV. 2020;7(2):e75.

Mishra K, Rampal J. The COVID-19 pandemic and food insecurity: a viewpoint on India. World Dev. 2020;135:105068.

Folayan MO, Ibigbami O, Brown B, El Tantawi M, Uzochukwu B, Ezechi OC, Aly NM, Abeldaño GF, Ara E, Ayanore MA, Ayoola OO. Differences in COVID-19 preventive behavior and food insecurity by HIV status in Nigeria. AIDS and Behavior. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-021-03433-3.

Zeballos E, Todd JE. The effects of skipping a meal on daily energy intake and diet quality. Public Health Nutr. 2022;23(18):3346–55.

Slawson DL, Fitzgerald N, Morgan KT. Position of the academy of nutrition and dietetics: the role of nutrition in health promotion and chronic disease prevention. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013;113(7):972–9.

Mirzaei H, McFarland W, Karamouzian M, Sharifi H. COVID-19 among people living with HIV: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2021;25(1):85–92.

Schaible UE, Kaufmann SHE. Malnutrition and infection: complex mechanisms and global impacts. PLoS Med. 2007;4(5):e115.

Ehwerhemuepha L, Bendig D, Steele C, Rakovski C, Feaster W. The effect of malnutrition on the risk of unplanned 7-day readmission in pediatrics. Hosp Pediatr. 2018;8(4):207–13.

Thompson B, Amoroso L, editors. Improving diets and nutrition: food-based approaches. CABI; 2014.

Omwanda VAMNMW, et al. Dietary practices and nutrition status of people living with HIV/AIDS aged 18–55 years attending Kisii teaching and referral hospital. Kisii County Int J Health Sci. 2020;10(3):94–102.

Dibari F, Bahwere P, le Gall I, Guerrero S, Mwaniki D, Seal A. A qualitative investigation of adherence to nutritional therapy in malnourished adult AIDS patients in Kenya. Public Health Nutr. 2012;15(2):316–23.

Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D, French S. Individual and environmental influences on adolescent eating behaviors. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-8223(02)90421-9.

Rodas-Moya S, Kodish S, Manary M, Grede N, de Pee S. Preferences for food and nutritional supplements among adult people living with HIV in Malawi. Public Health Nutr. 2016;19(4):693–702.

Houtzager LM. Nutrition in HIV: a review. J Postgrad Med. 2009;11:1.

Lawn SD, Harries AD, Anglaret X, Myer L, Wood R. Early mortality among adults accessing antiretroviral treatment programmes in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS (London, England). 2008. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0b013e32830007cd.

Liu E, Spiegelman D, Semu H, Hawkins C, Chalamilla G, Aveika A, et al. Nutritional status and mortality among HIV-infected patients receiving antiretroviral therapy in Tanzania. J Infect Dis. 2011;204:282–90.

Ammassari A, Murri R, Pezzotti P, Trotta MP, Ravasio L, de Longis P, et al. Self-reported symptoms and medication side effects influence adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy in persons with HIV infection. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001;28(5):445–9.

Somarriba G, Neri D, Schaefer N, Miller TL. The effect of aging, nutrition, and exercise during HIV infection. HIV/AIDS (Auckland, NZ). 2010;2010(2):191–201.

Haraj NE, el Aziz S, Chadli A, Dafir A, Mjabber A, Aissaoui O, et al. Nutritional status assessment in patients with Covid-19 after discharge from the intensive care unit. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2021 41.

Aguila EJT, Cua IHY, Fontanilla JAC, Yabut VLM, Causing MFP. Gastrointestinal manifestations of COVID‐19: impact on nutrition practices. Nutr Clin Pract. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/ncp.10554.

Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan. China Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506.

keith-Alcorn. https://www.aidsmap.com/news/mar-2021/underlying-health-conditions-play-major-role-increased-risk-hospitalisation-covid-19.nam-Aidsmap. 2021. Accessed 27 June 2022.

Cena H, Chieppa M. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19–SARS-CoV-2) and nutrition: is infection in italy suggesting a connection? Front Immunol. 2020;7:11.

de Pee S, Semba RD. Role of nutrition in HIV infection: review of evidence for more effective programming in resource-limited settings. Food Nutr Bull. 2010;31(4):S313–44.

Grobler L, Siegfried N, Visser ME, Mahlungulu SS, Volmink J. Nutritional interventions for reducing morbidity and mortality in people with HIV. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013.

World Health Organization. Nutrient requirements for people living with HIV/AIDS: report of a technical consultation. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. p. 13–5.

de Luis Román D, Bachiller P, Izaola O, Romero E, Martin J, Arranz M, Eiros Bouza JM, Aller R. Nutritional treatment for acquired immunodeficiency virus infection using an enterotropic peptide-based formula enriched with n-3 fatty acids: a randomized prospective trial. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2001;55(12):1048–52. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601276.

Filteau S, PrayGod G, Kasonka L, Woodd S, Rehman AM, Chisenga M, et al. Effects on mortality of a nutritional intervention for malnourished HIV-infected adults referred for antiretroviral therapy: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Med 2015 13(1).

Kaiser JD, Campa AM, Ondercin JP, Leoung GS, Pless RF, Baum MK. Micronutrient supplementation increases CD4 count in hiv-infected individuals on highly active antiretroviral therapy. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;42(5):523–8.

Houtzager LM. Nutrition in HIV: a review. Benin J Postgrad Med. 2009. https://doi.org/10.4314/bjpm.v11i1.48829.

Tirivayi N, Koethe J, Groot W. Clinic-based food assistance is associated with increased medication adherence among HIV-infected adults on long-term antiretroviral therapy in Zambia. J AIDS Clin Res 2012;3(171).

Ndekha MJ, van Oosterhout JJG, Zijlstra EE, Manary M, Saloojee H, Manary MJ. Supplementary feeding with either ready-to-use fortified spread or corn-soy blend in wasted adults starting antiretroviral therapy in Malawi: randomised, investigator blinded, controlled trial. BMJ. 2009. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b1867.

Gichunge CN, Hogan J, Sang E, Wafula S, Mwangi A, Petersen T et al. Role of food assistance in survival and adherence to clinic appointments and medication among HIV-infected patients on antiretroviral therapy (ART) in Western Kenya. Vienna: XVIII Int AIDS Conf 2010;

Morris SF, Wylie-Rosett J. Medical nutrition therapy: a key to diabetes management and prevention. Clin Diabetes 2010 28(1). https://doi.org/10.2337/diaclin.28.1.12.

Figueiredo SM, Penido MG, Guimaraes L, et al. Effects of dietary intervention on lipids profile of HIV infected patients on antiretroviral treatment (ART). Eur Sci J. 2013;9(12):32–49.

Vecchi VL, Soresi M, Giannitrapani L, Mazzola G, la Sala S, Tramuto F, et al. Dairy calcium intake and lifestyle risk factors for bone loss in HIV-infected and uninfected Mediterranean subjects. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;12:192. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-12-192.

Young JS. HIV and medical nutrition therapy. J Am Diet Assoc. 1997 97(10).

Gombart AF, Pierre A, Maggini S. A review of micronutrients and the immune system–working in harmony to reduce the risk of infection. Nutrients. 2020. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12010236.

Carr A, Maggini S. Vitamin C and immune function. Nutrients. 2017. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9111211.

Stephensen CB, Lietz G. Vitamin A in resistance to and recovery from infection: relevance to SARS-CoV2. Br J Nutr. 2021;126(11):1663–72.

Al-Sumiadai MM, Ghazzay H, Al-Dulaimy WZS. Therapeutic effect of vitamin A on severe COVID-19 patients. Eurasia J Biosci. 2020;14:7347–50.

Shakoor H, Feehan J, Mikkelsen K, al Dhaheri AS, Ali HI, Platat C, et al. Be well: a potential role for vitamin B in COVID-19. Maturitas. 2021;144:108–11.

Kandeel M, Al-Nazawi M. Virtual screening and repurposing of FDA approved drugs against COVID-19 main protease. Life Sci. 2020;15(251):117627.

Huang L, Wang L, Tan J, Liu H, Ni Y. High-dose vitamin C intravenous infusion in the treatment of patients with COVID-19: a protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2021;100(19):e25876.

Azkur AK, Akdis M, Azkur D, Sokolowska M, Veen W, Brüggen M, et al. Immune response to SARS-CoV-2 and mechanisms of immunopathological changes in COVID-19. Allergy. 2020;75(7):1564–81.

Wimalawansa SJ. Global epidemic of coronavirus-COVID-19: what we can do to minimze risksl. Eur J Biomed Pharm Sci. 2020;7:432–8.

Meydani SN, Leka LS, Fine BC, Dallal GE, Keusch GT, Singh MF, et al. Vitamin E and respiratory tract infections in elderly nursing home residents. JAMA. 2004 292(7).

Gombart AF. The vitamin D–antimicrobial peptide pathway and its role in protection against infection. Future Microbiol 2009 4(9).

Greiller CL, Martineau AR. Modulation of the immune response to respiratory viruses by vitamin D. Nutrients. 2015. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu7064240.

Udaya KV, Pavan G, Murti K, Kumar R, Dhingra S, Haque M, et al. Rays of immunity: role of sunshine vitamin in management of COVID-19 infection and associated comorbidities. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2021;46:21–32.

Grant W, Lahore H, McDonnell S, Baggerly C, French C, Aliano J, et al. Evidence that vitamin D supplementation could reduce risk of influenza and COVID-19 infections and deaths. Nutrients. 2020;12(4):988.

Meydani SN. Vitamin E supplementation and in vivo immune response in healthy elderly subjects. JAMA. 1997;277(17).

Wu D, Meydani S. Age-associated changes in immune function: impact of vitamin e intervention and the underlying mechanisms. Endocr Metab Immune Disord-Drug Targets. 2014;14(4):283–9.

Meydani SN. Vitamin E supplementation and in vivo immune response in healthy elderly subjects. JAMA. 1997 277(17).

Gammoh N, Rink L. Zinc in infection and inflammation. Nutrients. 2017 9(6).

Roth DE, Richard SA, Black RE. Zinc supplementation for the prevention of acute lower respiratory infection in children in developing countries: meta-analysis and meta-regression of randomized trials. Int J Epidemiol. 2010. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyp391.

Zhang J, Taylor EW, Bennett K, Saad R, Rayman MP. Association between regional selenium status and reported outcome of COVID-19 cases in China. Am J Clin Nutr. 2020;111(6):1297–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqaa095.

Infusino F, Marazzato M, Mancone M, Fedele F, Mastroianni CM, Severino P, et al. Diet supplementation, probiotics, and nutraceuticals in SARS-CoV-2 Infection: A Scoping Review. Nutrients. 2020. 8.

Di Renzo L, Merra G, Esposito E, De Lorenzo A. Are probiotics effective adjuvant therapeutic choice in patients with COVID-19? Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020;24(8):4062–3.

Raha S, Mallick R, Basak S, Duttaroy AK. Is copper beneficial for COVID-19 patients? Med Hypotheses. 2020;142:109814. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2020.109814.

Mossink JP. Zinc as nutritional intervention and prevention measure for COVID–19 disease. BMJ Nutr Prev Health. 2020;3(1):111–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjnph-2020-000095.

te Velthuis AJW, van den Worm SHE, Sims AC, Baric RS, Snijder EJ, van Hemert MJ. Zn2+ inhibits coronavirus and arterivirus RNA polymerase activity in vitro and zinc ionophores block the replication of these viruses in cell culture. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6(11):e1001176.

Razeghi Jahromi S, Moradi Tabriz H, Togha M, Ariyanfar S, Ghorbani Z, Naeeni S, et al. The correlation between serum selenium, zinc, and COVID-19 severity: an observational study. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21(1):899.

CDC. [Internet]. 2022 [cited 26 June 2022]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/. Centres for Disease Control and Prevention.

Broome CS, McArdle F, Kyle JA, Andrews F, Lowe NM, Hart CA, et al. An increase in selenium intake improves immune function and poliovirus handling in adults with marginal selenium status. Am J Clin Nutr 2004 80(1).

Bailey RL, West KP Jr, Black RE. The epidemiology of global micronutrient deficiencies. Ann Nutr Metab. 2015;66(Suppl. 2):22–3. https://doi.org/10.1159/000371618.

Hudayani F, Sartika RAD. Knowledge and behavior change of people living with hiv through nutrition education and counseling. Kesmas: Nat Public Health J 2016;10(3). https://doi.org/10.21109/kesmas.v10i3.947.

Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance Academy for Educational Development. Guide for nutritional care and support [online]. 2nd ed. Washington DC: Academy for Educational Development; 2004. Available from: http://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/C7B4ADF3EC3927E5C125740C003D03D9-fanta_oct2004.pdf. Accessed 28 June 2022.

Venter E, Gericke G, Bekker P. Nutritional status, quality of life and CD4 cell count of adults living with HIV/AIDS in the Ga-Rankuwa area (South Africa). South African J Clin Nutr. 2009;22(3). https://doi.org/10.1080/16070658.2009.11734233.

Gaikwad S, Garg S, Giri P, Gupta V, Singh M, Suryawanshi S. Impact of nutritional counseling on dietary practices and body mass index among people living with HIV/AIDS at a tertiary care teaching hospital in Mumbai. J Med Nutr Nutraceuticals. 2013;2(2):99.

Weiser SD, Young SL, Cohen CR, Kushel MB, Tsai AC, Tien PC, et al. Conceptual framework for understanding the bidirectional links between food insecurity and HIV/AIDS. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94(6). https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.111.012070.

Holdoway A. Nutritional management of patients during and after COVID-19 illness. Br J Community Nurs. 2020;25(Sup8):S6–10.

Deutz NEP, Bauer JM, Barazzoni R, Biolo G, Boirie Y, Bosy-Westphal A, et al. Protein intake and exercise for optimal muscle function with aging: recommendations from the ESPEN Expert Group. Clin Nutr. 2014;33(6):929–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2014.04.007.

Overview | Nutrition support for adults: oral nutrition support, enteral tube feeding and parenteral nutrition | Guidance | NICE. Nice.org.uk. 2022 Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg32. Accessed 28 June 2022.

British Association of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. Practical guidance for using ‘MUST’ to identify malnutrition during the COVID-19 pandemic: Malnutrition Action Group (MAG) update. 2020 covid-mag-update-may-2020.pdf (bapen.org.uk). Accessed 27 June 2022.

McLinden T, Stover S, Hogg RS. HIV and food insecurity: a syndemic amid the COVID-19 pandemic. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(10). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-02904-3.

People Living with HIV and TB and their families in context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Docs.wfp.org. 2022 Available from: https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP-0000115429/download/. Accessed 28 June 2022.

Policarpo S, Machado M v, Cortez-Pinto H. Telemedicine as a tool for dietary intervention in NAFLD-HIV patients during the COVID-19 lockdown: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnesp.2021.03.031.

Waterfield KC, Shah GH, Etheredge GD, Ikhile O. Consequences of COVID-19 crisis for persons with HIV: the impact of social determinants of health. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):299. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10296-9.

Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the Department of Pharmaceuticals, Ministry of Chemicals and Fertilizers, Government of India, for providing necessary facilities.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KM, SD, NK, SS, and VR conceptualised the topic, FAS wrote the first draft of the manuscript. MM and VUK drafted the pictographic designs, FAS and VUK edited the manuscript and are responsible for final draft. All the authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Covid-19

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

S, F.A., Madhu, M., Udaya Kumar, V. et al. Nutritional Aspects of People Living with HIV (PLHIV) Amidst COVID-19 Pandemic: an Insight. Curr Pharmacol Rep 8, 350–364 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40495-022-00301-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40495-022-00301-z