Abstract

Background

Little is known about the experience of the male breast cancer patient. Mastectomy is often offered despite evidence that breast-conserving surgery (BCS) provides similar outcomes.

Methods

Two concurrent online surveys were distributed from August to October 2020 via social media to male breast cancer (MBC) patients and by email to American Society of Breast Surgeon members. The MBC patients were asked their opinions about their surgery, and the surgeons were asked to provide surgical recommendations for MBC patients.

Results

The survey involved 63 MBC patients with a mean age of 62 years (range, 31–79 years). Five MBC patients (7.9 %) stated that their surgeon recommended BCS, but 54 (85.7 %) of the patients underwent unilateral, and 8 (12.7 %) underwent bilateral mastectomy. Most of the patients (n = 60, 96.8 %) had no reconstruction. One third of the patients (n = 21, 33.3 %) felt somewhat or very uncomfortable with their appearance after surgery. The response rate was 16.5 % for the surgeons. Of the 438 surgeons who answered the survey, 298 (73.3 %) were female, 215 (51.7 %) were fellowship-trained, and 244 (58.9 %) had been practicing for 16 years or longer. More than half of surgeons (n = 259, 59.1 %) routinely offered BCS to eligible men, and 180 (41.3 %) stated they had performed BCS on a man with breast cancer. Whereas 89 (20.8 %) of the surgeons stated that they routinely offer reconstruction to MBC patients, 87 (20.3 %) said they do not offer reconstruction, 96 (22.4 %) said they offer it only if the patient requests it, and 157 (36.6 %) said they never consider it as an option.

Conclusions

The study found discordance between MBC patients’ satisfaction with their surgery and surgeon recommendations and experience. These data present an opportunity to optimize the MBC patient experience.

Similar content being viewed by others

Male breast cancer (MBC) is a rare occurrence accounting for less than 1 % of all newly diagnosed breast cancers in the United States.1 Men are often excluded from clinical trials, and as a result, the management of MBC generally is extrapolated from clinical trials of breast cancer management for women.2, 3

Historically, MBC has been treated with mastectomy without reconstruction, but a growing body of literature supports the safety and feasibility of breast conservation surgery (BCS) for this population.4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12. In fact, the current National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines for men with breast cancer support BCS for eligible candidates.3 The rates of BCS for men with breast cancer range from 4 to 19.8 %.5,6,7,8,9,10, 13 Similarly, contralateral prophylactic mastectomy also is uncommon in this population, with reported rates ranging from 6.1 to 6.7 %.10, 14 Additionally, although various forms of reconstruction after mastectomy in MBC have been reported, they are not performed commonly.10, 15

One study of 1773 MBC patients treated during the past decade showed that only 4.2 % of men undergoing mastectomy had reconstruction, most commonly with implant placement.10 This finding demonstrates that reconstruction after mastectomy may be an option of interest to men and that the opportunity may exist for more routine discussion of reconstruction with MBC patients. Beyond these reports, however, little is known about the MBC surgical experience from the patients’ perspective.16, 17

To date, no studies have investigated the experience of breast surgeons treating MBC. Likewise, no research has focused specifically on surgeon recommendations for these patients regarding breast-conserving surgery, reconstruction after mastectomy, or bilateral mastectomy for a man with breast cancer.

This study aimed to assess MBC patients’ opinions and perspectives about the surgical approach for their breast cancer and to compare their experiences with surgeon recommendations for MBC.

Methods

Survey Development

An MBC patient experience survey was developed to assess the level of information patients received about surgical choices and comfort with the appearance of their chest wall and scar after surgery. The survey items were chosen based on another survey of women with breast cancer, the WhySurg study,18 in which women were asked about surgical choice and their decisional satisfaction. The MBC survey was examined and tested by five MBC patients in the community for readability, vocabulary, and time to complete it before its official launching.

Concurrently, a survey for breast surgeons was developed to assess surgeons’ current opinions and perspectives on their surgical approach to men with breast cancer and comfort level in changing their approach. After development of the physician survey, it was reviewed by 15 members of the American Society of Breast Surgeons (ASBrS) in practice for at least 3 years from across the country before its distribution.

Survey Administration and Eligibility

An Institutional Review Board (IRB) exemption was obtained from the NorthShore University HealthSystem due to the anticipated low risk for study participants. Patients were eligible for participation if they were English-reading biologic males with a history of mastectomy or partial mastectomy for breast cancer diagnosed within 10 years of the survey administration. Patients were eligible for participation regardless whether they had undergone reconstruction. Five questions were used to screen for eligibility, and patients who did not meet the eligibility criteria were disqualified and not permitted to complete the remainder of the survey.

Surgeons were eligible for participation if they were active members of the ASBrS at the time of the survey administration. It was not required that breast surgeons be fellowship-trained or perform only breast surgery. Nor was there a requirement concerning the number of MBC patients the surgeon had treated.

The patient surveys were posted online via several social media portals including Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram as well as MBC advocacy groups such as the Male Breast Cancer Coalition between August 2020 and October 2020. The surveys were distributed to ASBrS members by email between August 2020 and October 2020.

For both surveys, participation was voluntary. No financial or other incentive was provided. The surveys were completed anonymously, and personal identifying information was not collected.

Measures

The MBC patient survey (“Appendix 1”) was composed of two sections. The first section asked participants their opinions about different surgical procedures for their breast and their preferences regarding these procedures. A five-level Likert scale was used to assess the level of patient comfort with the appearance and feel of their chest postoperatively.

The second section included questions that addressed the patient’s diagnosis and demographic information including patient age, family history of cancer, genetic testing, type of surgery performed, stage of disease, non-surgical treatment, race, ethnicity, marital status, education level, and income. This section also had two open-ended questions regarding what bothered the patient most about the appearance or feel of his chest and scar area and whether he had additional information he wanted to share with the research team.

The physician survey (“Appendix 2”) was composed of three sections. In the first section, the surgeons were presented with a specific case scenario of an MBC patient who had a 1.5-cm grade 2 hormone receptor-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-neu, not overexpressed invasive ductal carcinoma of the right breast at 10 o’clock, 5 cm from the nipple without lymphadenopathy on exam and negative genetic testing. The surgeons were asked about their level of comfort and concerns with management recommendations regarding breast-conserving surgery, reconstruction, and axillary node surgery. The case scenario and associated questions are presented in Table 5. The second section presented seven different MBC patient scenarios and asked the physicians what their level of recommendation for bilateral mastectomy would be based on a four-level scale including “strong recommendation,” “somewhat strong recommendation,” “weak recommendation,” and “no recommendation at all.” The third section contained questions on clinical experience and demographic information including number of MBC patients treated per year, total patients with breast cancer treated per year, years in practice, fellowship training, country of residence, country of practice, U.S. state of practice, practice setting, biologic sex of the surgeon, and gender identification.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were reported as frequency with percentage or as mean with standard deviation to describe MBC patient characteristics, surgeon characteristics, and opinions and perceptions about the surgical approach to MBC. The open-ended survey responses from the MBC patients were grouped according to theme and summarized using descriptive statistics. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patient Demographics, Oncologic Characteristics, and Reported Management

The online survey received responses from 63 MBC patients. The demographic and oncologic characteristics of the patient respondents are reported in Table 1. The mean age of patient respondents was 62 ± 11 years (range 31–79 years), and the majority reported their race/ethnicity to be non-Hispanic white (n = 55, 94.8 %). Most of the respondent patients (n = 52, 91.2 %) had been treated in the United States, with representation from various regions of the country including the Northeast (n = 10, 18.5 %), the Midwest (n = 9, 16.7 %), the South (n = 19, 35.2 %), and the West (n = 11, 20.4 %).

Nearly three fourths (n = 47, 74.6 %) of the patient respondents were 51 to 75 years old at the time of diagnosis. Of the 63 patients, 58 (92 %) reported that it had been 1 to 10 years since their diagnosis. The majority (n = 56, 88.9 %) reported stage 1, 2, or 3 disease at diagnosis. Most of the respondents (n = 54, 85.7 %) had a family history of cancer, and almost all (n = 60, 95.2 %) had undergone genetic testing, with 57 (90.5 %) specifically reporting BRCA1/2 testing. The respondents included 26 (43.3 %) patients who had testing before surgery, 35 (53.9 %) patients who did not receive their results until after surgery, and 11 (18.3 %) patients who reported having an abnormal gene.

Most of the patients (n = 54, 85.7 %) reported treatment with unilateral mastectomy, although 8 (12.7 %) patients had undergone bilateral mastectomy, and 1 (1.6 %) patient had been treated with partial mastectomy. Nearly all the patients (61, 98.6 %) had their nipples removed. Most of the patients (60, 96.8 %) did not have reconstruction. Of those who had reconstruction, one (1.6 %) had an autologous flap, and one (1.6 %) had a local tissue advancement flap. Radiation was reported by 37 (58.7 %) of the patients, with 36 (97.3 %) receiving it in the adjuvant setting. More than three fourths of the respondents (n = 49, 77.8 %) were treated with chemotherapy, with 9 (18.8 %) treated in the neoadjuvant setting and 40 (83.3 %) receiving adjuvant chemotherapy. At the time of the survey, 8 (12.7 %) patients reported living with metastatic cancer.

Demographics of the Breast Surgeon Survey Respondents

The response rate for the surgeons was 16.5 % (438/2650). The demographic characteristics of the surgeon respondents are reported in Table 2. The majority of the surgeons were female (n = 298, 73.3 %). Slightly more than half (n = 215, 51.7 %) were fellowship-trained, and 244 (58.9 %) had been in practice 16 years or longer. Most of the surgeons (n = 387, 93 %) reported residing in the United States across the Northeast (n = 94, 24.6 %), Midwest (n = 80, 20.9 %), South (n = 128, 33.5 %), and West (n = 79, 20.7 %).

The surgeon respondents were employed in a variety of practice settings, including the academic employed/university setting (n = 83, 20.2 %), the academic employed/community setting (n = 48, 11.7 %), the hospital employed/community setting (n = 166, 40.4 %), and private practice (n = 105, 25.6 %). Whereas 282 (67.8 %) of the surgeons reported treating more than 100 total breast cancer patients per year, 403 (97.1 %) treated fewer than five MBC patients per year.

Patient Opinions and Perspectives on Decision-Making for Surgery

The majority of the MBC patients felt they had a choice in the decision for surgery (n = 51, 81 %) or had all the information needed to make a decision (n = 47, 74.6 %) for surgery (Table 3). Five (7.9 %) of the MBC patients stated that their surgeon recommended BCS, whereas 54 (85.7 %) reported that their surgeon recommended unilateral mastectomy and 10 (15.9 %) reported that their surgeon recommended bilateral mastectomy.

Approximately one third (34.9 %) of the patients felt very comfortable with their appearance after surgery, but a similar number reported feeling somewhat or very uncomfortable (n = 21, 33.3%).

When asked what bothered them most about the appearance or feel of their chest and scar area or whether they had additional information they wanted the research team to know, 31 patients provided open-ended comments. Representative comments are reported verbatim in Table 4. Common themes expressed were feeling “unbalanced” or asymmetric (n = 9, 29 %), feeling self-conscious about looking “abnormal” (n = 9, 29 %), feeling their chest was “flat, caved, or indented” (n = 5, 16.1 %), having discomfort or skin tightness (n = 5, 16.1 %), or having concerns about their scar (n = 2, 6.5 %) or lack of nipple (n = 2, 6.5 %) (multiple responses permitted).

Breast Surgeon Recommendations for Surgery Based on a Case Scenario of Early-Stage MBC

In response to the clinical case scenario (Table 5), more than half (n = 227, 51.8 %) of the surgeon respondents felt very comfortable recommending BCS. One fourth (n = 108, 24.8 %) of the surgeons cited concerns about inadequate data regarding local recurrence risk. As reported, 46 (10.6 %) of the surgeons were concerned about inadequate data regarding safety and efficacy of radiation therapy in this setting, 90 (20.6 %) were concerned about cosmetic outcome, and 86 (19.7 %) cited no experience performing BCS for men (multiple responses permitted).

If the patient were to have a mastectomy, 87 (20.3 %) of the surgeons stated that they did not offer post-mastectomy reconstruction to men, 96 (22.4 %) reported that they offered only post-mastectomy reconstruction if specifically requested by the patient, and another 157 (36.6 %) stated that they had never considered reconstruction an option until taking the survey. The surgeons varied regarding the type of reconstruction they would offer, with 112 (29.9 %) offering fat grafting, 45 (12 %) offering an autologous flap, 30 (8 %) offering an implant-based reconstruction, and 75 (20 %) offering an oncoplastic lumpectomy with contralateral reduction.

The surgeons also were divided regarding whether they would offer the patient nipple-sparing mastectomy, with 75 (17.7 %) stating that they “never” would, 87 (20.5 %) stating that they would only if the patient were undergoing reconstruction, 146 (34.4 %) stating that they would regardless of reconstruction, and 116 (27.4 %) stating that they would only if requested by the patient. Most of the surgeons (n = 346, 80.7 %) stated that they would not offer bilateral mastectomy to the patient in the scenarios presented.

Nearly half (n = 207, 47.7 %) of the surgeons stated that the evidence supporting BCS for MBC was weak. Slightly more than half (n = 259, 59.1 %) of the surgeons reported routinely offering BCS to eligible men. Less than half (n = 180, 41.3 %) of the surgeons stated that they had performed BCS on a man with breast cancer.

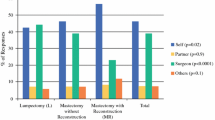

Surgeon Level of Recommendation for Bilateral Mastectomy

The surgeons were presented with a series of hypothetical MBC case scenarios and asked the strength of their recommendation for bilateral mastectomy (Fig. 1). Of the surgeon respondents, 130 (29.7 %) “strongly recommended” bilateral mastectomy to men with BRCA pathogenic variants or likely pathogenic variants, and 79 (18 %) had “no recommendation at all.” For any man with a newly diagnosed breast cancer, no surgeon stated that he or she would strongly recommend bilateral mastectomy, and 275 (63.1 %) stated that they had “no recommendation at all.”

The responses to the other scenarios varied, with many surgeons stating that they had “no recommendation at all” for men with larger breasts for which unilateral mastectomy might result in significant asymmetry (n = 119, 27.2 %), MBC patients with confirmed moderate-penetrance pathologically variant genes (n = 134, 30.6 %), MBC patients 40 years old or younger (n = 164, 37.6 %), or MBC patients with a significant family history of breast cancer (n = 192, 44 %).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the largest study of MBC patient experience and the only study to report on the breast surgeon experience treating MBC. We found that men undergoing mastectomy without reconstruction are often dissatisfied with their cosmetic outcomes, but that surgeons often do not offer reconstruction or even consider it as an option. Likewise, surgeons expressed willingness to perform breast-conserving surgery for men with breast cancer, but less than half had experience performing BCS for men.

In open-ended responses, patients reported feeling “unbalanced” or asymmetric, looking “abnormal,” feeling “flat, caved, or indented,” having discomfort or skin tightness, or having concerns about their scar or lack of nipple. These themes are in concordance with other published reports of the MBC patient experience.

Men with breast cancer commonly experience altered, negative body image relating to their cancer diagnosis and treatment, and report the use of body concealment practices, including adjusting clothing choices or avoiding situations in which they normally would bare their chest (i.e., swimming) in order to hide their surgical scars.16, 17, 19 Findings show that MBC patients with negative perceptions of their postoperative appearance are more likely to experience cancer-specific distress, and that altered body image is the biggest risk factor for depression in this population.19 Women also experience body image issues postoperatively, but this occurs to a lesser extent among women undergoing breast reconstruction or BCS versus mastectomy alone.20,21,22 This suggests that men also may have improved health-related quality of life and body image from BCS or reconstruction.

Only one man with breast cancer who responded to our survey reported treatment with a partial mastectomy. In contrast to the patient-reported experience, 59.1 % of the surgeon respondents routinely offered BCS to eligible men, and 41.3 % had performed BCS on a man with breast cancer. This was despite the belief held by almost half of the surgeons that the evidence to support BCS for MBC was weak.

The rates of MBC BCS in the literature range from 4 % to 19.8 %.5,6,7,8,9,10, 13 In multiple database analyses of men with breast cancer, partial mastectomy was not associated with worse breast cancer-specific survival or overall survival than mastectomy.6, 8, 11 In fact, partial mastectomy with adjuvant radiation was found to be associated with better overall survival than partial mastectomy alone or total mastectomy with or without adjuvant radiation in a National Cancer Database (NCDB) analysis of MBC patients treated between 2004 and 2014.7 Collectively, these findings support the current NCCN guidelines for men with breast cancer, which state that BCS for men is “associated with equivalent outcomes to mastectomy and is safe and feasible” and that “decisions about BCS versus mastectomy should be made according to similar criteria” as for women.3, 5,6,7,8,9,10,11

The current NCCN guidelines also recommend hereditary cancer testing for men with breast cancer diagnosed at any age, and almost all the patient survey respondents in this study reported genetic testing.23 Notably, 43.3 % of the MBC patients who responded to the survey did not undergo testing until after surgery. Of the surgeon respondents, 29.7 % strongly recommended bilateral mastectomy to men with a BRCA1/2 pathogenic variant or likely pathogenic variant. This aligns with Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data from 2014–2016 in which women who tested positive for a BRCA1/2 pathogenic variant were more likely to receive bilateral mastectomy for a unilateral tumor.24

The cumulative lifetime MBC risk for a patient with a BRCA2 pathogenic variant is 12.5 %.25 Although this is significantly higher than the population risk of 0.13 % for breast cancer in a man without a pathogenic variant, it is much lower than the lifetime risk of breast cancer among women with a pathogenic variant in BRCA1 or BRCA2, which approaches 72 % and 69 %, respectively.26 The reported rate for the development of a second contralateral breast cancer in patients with MBC indicates a 30- to 52-fold increased risk, comparable with the increased risk of contralateral breast cancer for women with the BRCA1 (40 %) and BRCA2 (26 %) pathogenic variants.26,27,28,29

The current NCCN guidelines recommend discussing the option of risk-reducing mastectomy for individuals assigned female sex at birth who carry a BRCA1/2 pathogenic or likely pathogenic variant, but do not recommend bilateral mastectomy outright or address recommendations for men.23 Likewise, the NCCN guidelines do not recommend bilateral mastectomy for men with pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants, but this may be an option that men with breast cancer are interested in discussing.3

One patient in the current study who desired a bilateral mastectomy expressed dissatisfaction that his surgeon did not offer it as an option, and in a National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) database analysis of MBC treatment patterns, 6.7 % of the patients elected contralateral prophylactic analysis.10

The same NSQIP database analysis showed that 4.2 % of the men with breast cancer underwent immediate breast reconstruction.10 The low rate of reconstruction in the literature may be due to the fact that many surgeons do not offer reconstruction or even consider it as an option, as reported by more than 50 % of the surgeons who responded to our survey.

The reconstructive options for men with breast cancer can include tissue expander placement, prosthetic implant, nipple-areolar reconstruction, mammoplasty with or without prosthetic implant, or flap-based reconstruction.10 The flap-based reconstruction options in this setting include a transverse rectus abdominis (TRAM) flap, a deep inferior epigastric artery perforator (DIEP) flap, a latissimus dorsi (LD) flap, and a delto-pectoral flap.10, 15 One particular benefit of a TRAM or DIEP flap for men is that it replaces not only skin and fat but also hair in what is normally a hair-bearing area in these patients.15

The oncoplastic techniques used for women also could be applied for men with breast cancer. For example, for men with gynecomastia, an oncoplastic reduction and contralateral reduction mammaplasty could be considered.15, 30

Additionally, reports have described nipple-sparing mastectomy for men with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS).31,32,33 Because surgical complication rates for men with breast cancer are low,10 we recommend that reconstructive options be discussed with all eligible patients. Notably, however, the 1998 Women’s Health and Cancer Rights Act, which provides protection for women who choose to have breast reconstruction with a mastectomy, does not also provide the same protection for men.34 Insurance coverage may vary, which may help to explain the low rates of reconstruction in this population.

A limitation of our study was the low volume of patients and surgeons who participated. However, this study had a relatively large number of patient respondents compared with other studies evaluating this population, and no studies to date have asked surgeons their surgical preferences for MBC. We attribute the low response rate in part to administration of the survey during the COVID-19 pandemic.

We also acknowledge possible selection bias of self-selected survey respondents who may not be representative of the average MBC patient or breast surgeon. Indeed, 40 % of the surgeons in our study stated that they had performed BCS for men with breast cancer, but observational datasets show that only up to 16 % of men undergo BCS for their breast cancer.5,6,7,8,9,10

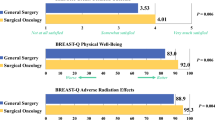

Additionally, although we had the surveys reviewed by a convenience sample of both patient advocates and surgeons before distribution, we did not perform a more rigorous validation process. A commonly used validated patient-reported outcome measure, the BREAST-Q survey, assesses both pre- and postoperative patient satisfaction and health-related quality of life specific for breast surgery.35 However, it was not designed for or validated with male patients, and has questions that are not applicable to men, for example, regarding how comfortably a bra fits. Furthermore, validated patient-reported outcome measures do not necessarily allow for open-ended responses, which can provide important insight and context to survey responses.36

When men are treated for breast cancer, we recommend adherence to the NCCN guidelines for MBC, including consideration of BCS for appropriate candidates and genetic testing for all men.3 If BCS is achieved, adjuvant radiation should be administered following the current guidelines for breast cancer in women. If BCS is not feasible for an MBC patient, surgeons should discuss the option of bilateral mastectomy and reconstruction and collaborate with an experienced plastic and reconstructive surgeon if breast mound reconstruction is desired. We also advocate for the inclusion of men in clinical trials, the creation of trials specific for MBC, and the enrollment of patients in a prospective international registry similar to the International Programme of Breast Cancer in Men (BIG 2-07/EORTC-10085p=BCG), a global effort aiming to characterize MBC biology and develop clinical trials.5

References

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:7–33. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21654.

Duma N, Hoversten KP, Ruddy KJ. Exclusion of male patients in breast cancer clinical trials. JNCI Cancer Spectrum. 2018;2:18. https://doi.org/10.1093/jncics/pky018.

Rashmi Kumar N, Burns J, Abraham J, et al. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Breast Cancer, Version 2.2022. 2022. Available at https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast.pdf. Accessed 10 Apr 2022.

Gao Y, Goldberg JE, Young TK, Babb JS, Moy L, Heller SL. Breast cancer screening in high-risk men: a 12-year longitudinal observational study of male breast imaging utilization and outcomes. Radiology. 2019;293:282–91. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2019190971.

Cardoso F, Bartlett JMS, Slaets L, et al. Characterization of male breast cancer: results of the EORTC 10085/TBCRC/BIG/NABCG International Male Breast Cancer Program. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:405–17. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdx651.

Cloyd JM, Hernandez-Boussard T, Wapnir IL. Outcomes of partial mastectomy in male breast cancer patients: analysis of SEER, 1983–2009. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:1545–50. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-013-2918-5.

Bateni SB, Davidson AJ, Arora M, et al. Is breast-conserving therapy appropriate for male breast cancer patients? A National Cancer Database Analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26:2144–53. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-019-07159-4.

Zaenger D, Rabatic BM, Dasher B, Mourad WF. Is breast-conserving therapy a safe modality for early-stage male breast cancer? Clin Breast Cancer. 2016;16:101–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clbc.2015.11.005.

Leone JM, Zwenger AO, Leone BA, Vallejo CT, Leone JP. Overall survival of men and women with breast cancer according to tumor subtype. Am J Clin Oncol. 2019;42:215–220.

Elmi M, Sequeira S, Azin A, Elnahas A, McCready DR, Cil TD. Evolving surgical treatment decisions for male breast cancer: an analysis of the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) database. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2018;171:427–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-018-4830-y.

Fields EC, Dewitt P, Fisher CM, Rabinovitch R. Management of male breast cancer in the United States: a Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;87:747–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.07.016.

Lin AP, Huang TW, Tam KW. Treatment of male breast cancer: meta-analysis of real-world evidence. Br J Surg. 2021;108:1034–42. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjs/znab279.

Jemal A, Lin CC, DeSantis C, Sineshaw H, Freedman RA. Temporal trends in and factors associated with contralateral prophylactic mastectomy among US men with breast cancer. JAMA Surgery. 2015;150:1192–4. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2015.2657.

Yadav S, Karam D, Bin Riaz I, et al. Male breast cancer in the United States: treatment patterns and prognostic factors in the 21st century. Cancer. 2020;126:26–36. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.32472.

Fentiman IS. Surgical options for male breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2018;172:539–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-018-4952-2.

Quincey K, Williamson I, Winstanley S. “Marginalised malignancies”: a qualitative synthesis of men’s accounts of living with breast cancer. Soc Sci Med. 2016;149:17–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.11.032.

Levin-Dagan N, Baum N. Passing as normal: negotiating boundaries and coping with male breast cancer. Soc Sci Med. 2021;284:114239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114239.

Deliere A, Attai D, Victorson D, et al. Patients undergoing bilateral mastectomy and breast-conserving surgery have the lowest levels of regret: the WhySurg Study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2021;28:5686–97. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-021-10452-w.

Brain K, Williams B, Iredale R, France L, Gray J. Psychological distress in men with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:95–101. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2006.10.064.

Zehra S, Doyle F, Barry M, Walsh S, Kell MR. Health-related quality of life following breast reconstruction compared to total mastectomy and breast-conserving surgery among breast cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer. 2020;27:534–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12282-020-01076-1.

Fang SY, Shu BC, Chang YJ. The effect of breast reconstruction surgery on body image among women after mastectomy: a meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;137:13–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-012-2349-1.

Lee C, Sunu C, Pignone M. Patient-reported outcomes of breast reconstruction after mastectomy: a systematic review. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;209:123–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.02.061.

Buys SS, Dickson P, Domchek SM, et al. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Detection, Prevention, and Risk Reduction: Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Breast, Ovarian, and Pancreatic. Version 2.2022. 2022. Available at https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/genetics_bop.pdf. Accessed 10 Apr 2022.

Kurian AW, Ward KC, Abrahamse P, et al. Association of germline genetic testing results with locoregional and systemic therapy in patients with breast cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6:e196400. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.6400.

Roed Nielsen H, Petersen J, Therkildsen C, Skytte AB, Nilbert M. Increased risk of male cancer and identification of a potential prostate cancer cluster region in BRCA2. Acta Oncol. 2016;55:38–44. https://doi.org/10.3109/0284186X.2015.1067714.

Kuchenbaecker KB, Hopper JL, Barnes DR, et al. Risks of breast, ovarian, and contralateral breast cancer for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. JAMA. 2017;317:2402–2416. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.7112.

Grenader T, Goldberg A, Shavit L. Second cancers in patients with male breast cancer: a literature review. J Cancer Survivorship. 2008;2:73–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-008-0042-5.

Satram-Hoang S, Ziogas A, Anton-Culver H. Risk of second primary cancer in men with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9:R10. https://doi.org/10.1186/bcr1643.

Auvinen A, Curtis RE, Ron E. Risk of subsequent cancer following breast cancer in men. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1330–2. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/94.17.1330.

Brenner P, Berger A, Schneider W, Axmann HD. Male reduction mammoplasty in serious gynecomastias. Aesth Plast Surg. 1992;16:325–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01570695.

Noor L, McGovern P, Bhaskar P, Lowe JW. Bilateral DCIS following gynecomastia surgery: role of nipple-sparing mastectomy: a case report and review of literature. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2011;2:106–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijscr.2011.02.009.

Tari DU, Morelli L, Guida A, Pinto F. Male breast cancer review: a rare case of pure dcis: imaging protocol, radiomics, and management. Diagnostics. 2021;11:2199. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11122199.

Luini A, Gatti G, Brenelli F, et al. Male breast cancer in a young patient treated with nipple-sparing mastectomy: case report and review of the literature–PubMed. Tumori. 2007;93:118–20.

Women’s Health and Cancer Rights | U.S. Department of Labor. Retrieved 12 April 2022 at https://www.dol.gov/general/topic/health-plans/womens.

Pusic AL, Klassen AF, Scott AM, Klok JA, Cordeiro PG, Cano SJ. Development of a new patient-reported outcome measure for breast surgery: the BREAST-Q. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:345–53. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181aee807.

Vickers AJ. Validation of patient-reported outcomes: a low bar. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:1990–2. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.19.01126.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosure

Anna Chichura received educational and travel support from Hologic. Deanna J. Attai received a research grant from Pfizer and NCCN. Katharine Yao received a research grant from the JWCI foundation. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1: MBC patient survey

What is your biologic sex?

-

Male

-

Female → (disqualified)

-

Choose not to answer → (disqualified)

1. Have you been diagnosed with breast cancer?

-

Yes

-

No → (disqualified)

2. Did you have surgery for your breast cancer?

-

Yes

-

No → (disqualified)

Please answer the following questions pertaining to your breast cancer diagnosis:

3. How long ago were you diagnosed with breast cancer?

If you were diagnosed with breast cancer more than once, please enter the time since the first diagnosis:

-

Less than 1 year ago

-

1 to 5 years ago

-

6 to 10 years ago

-

11 to 15 years ago (>10 years ago → disqualified)

-

>15 years ago → (disqualified)

4. How old were you when you were diagnosed with breast cancer?

If you were diagnosed with breast cancer more than once, please enter your age at the time of the first diagnosis:

-

0–17 years old (disqualified)

-

18– 35 years old

-

36–50 years old

-

51–75 years old

-

>75 years old

5. What was your cancer stage at the time of diagnosis?

If you were diagnosed with breast cancer more than once, please enter the stage at the time of the first diagnosis:

-

0

-

1, 2, or 3

-

4 (metastatic, spread to other organs)

-

I was told my cancer was “early stage” but do not know the exact number.

-

I was told my cancer was “late stage” or “advanced” but do not know the exact number.

-

I do not know or I do not remember.

The following questions refer to your breast cancer surgery and treatment:

6. What operation did you have? Check all that apply

Mastectomy is complete removal of the breast

Lumpectomy is removal of the tumor only; the breast is not removed

-

Single (only side of the cancer) mastectomy and removal of the nipple

-

Single (only side of the cancer) mastectomy without removal of the nipple

-

Double (both sides) mastectomy and removal of one or both nipples

-

Double (both sides) mastectomy without removal of either nipple

-

Lumpectomy and removal of the nipple

-

Lumpectomy without removal of the nipple

7. Did you have any type of reconstructive surgery?

Reconstructive surgery might be performed by your breast surgeon or a plastic surgeon and could include procedures to fill in a defect after lumpectomy, make the chest wall after mastectomy more natural-appearing, or re-create a nipple if the nipple was removed.

-

I had reconstructive surgery at the time of lumpectomy or mastectomy.

-

I had reconstructive surgery after the lumpectomy or mastectomy.

-

I did not have any reconstructive surgery → (skip to Q10) .

8. What type of reconstruction did you have? Please read the choices carefully and choose the one that best fits your situation:

-

Tissue expander with eventual implant placement or plan for implant placement

-

Direct to implant (no tissue expander)

-

Flap using your own body fat and/or muscle including DIEP, TRAM, latissimus flap and other

-

Combination of tissue expander/implant + flap

-

Liposuction and fat injections

-

Use of skin and fat (from chest area)

-

Other, please specify

9. Which of the following best characterizes the discussion with your surgeon regarding options for surgery?

-

My surgeon recommended single mastectomy.

-

My surgeon recommended double mastectomy.

-

My surgeon recommended lumpectomy.

-

Other, please specify

10. Do you feel you had a choice in the decision for surgery?

-

Yes

-

No

11. Do you feel you had adequate information about all of your surgical options so that you could make the right decision for you?

-

Yes

-

No

12. How comfortable are you with the appearance and feel of your chest and scar after surgery?

-

Very comfortable, the appearance or feel do not bother me

-

Somewhat comfortable, the appearance or feel do bother me somewhat

-

Neutral–neither comfortable nor uncomfortable

-

Somewhat uncomfortable: I am somewhat bothered by the appearance or feel.

-

Very uncomfortable: I am very bothered by the appearance or feel.

13. Please comment what bothers you most about the appearance or feel of your chest and scar area: (free response)

14. Have you had radiation therapy to the breast or chest, on the side of mastectomy? Please read the choices carefully and choose the one that best fits your situation:

-

I had radiation before my mastectomy for previous breast cancer.

-

I had radiation after my mastectomy due to breast cancer.

-

I had radiation for Hodgkin’s lymphoma or other medical condition before my mastectomy.

-

I had radiation for Hodgkin’s lymphoma or other medical condition after my mastectomy.

-

I received radiation but did not or have not yet had surgery.

-

I have not had radiation to the breast or chest.

15. Did you receive chemotherapy? Please do not consider endocrine therapy such as tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors (anastrozole/arimidex, letrozole/femara, exemestane/aromasin) in answering this question. Please read the choices carefully and choose the one that best fits your situation:

-

I received chemotherapy before my mastectomy surgery, for previous breast or non-breast cancer.

-

I received chemotherapy before my mastectomy surgery, for my breast cancer.

-

I received chemotherapy after my mastectomy surgery, for my breast cancer.

-

I received chemotherapy after my mastectomy surgery, for non-breast cancer.

-

I received chemotherapy but did not or have not yet had surgery.

-

I have not received chemotherapy.

16. Are you currently living with metastatic cancer? Metastatic cancer is breast cancer that has spread from the breast to other organs such as liver, lungs, bone or brain. This is also termed stage 4:

-

Yes

-

No

Please answer the following questions pertaining to your family history and genetics:

17. Do you have any relatives with cancer in your family? Please include first-, second-, and third-degree male and female relatives including parents, brothers, sisters, great- and great-great grandparents, aunt, uncles, cousins

-

Breast cancer

-

Ovarian cancer

-

Colon cancer

-

Prostate cancer

-

Pancreatic cancer

-

Melanoma skin cancer

-

Other, please specify

-

I do not have any history of cancer in my family.

18. Did you have genetic testing before surgery or after surgery?

-

I was tested before surgery and got my results before surgery.

-

I was tested before surgery but didn’t get my results until after surgery.

-

I was tested after surgery.

-

I was tested but I did not or have not yet had surgery.

-

I did not undergo genetic testing → (skip to Q21) .

19. Did you undergo genetic testing for a BRCA (BRCA 1 or 2) or other genetic mutation?

-

I was tested for BRCA 1 and 2.

-

I was tested for BRCA 1 and 2 as well as other breast cancer related genes.

20. Were you found to have an abnormal BRCA gene (BRCA 1 or 2 mutation) or other abnormal gene that might contribute to breast cancer risk? Please consider a variant of uncertain significance (VUS) to be “no” when responding to this question:

-

Yes

-

No

The following questions pertain to your current demographic information:

21. How much do you weigh in pounds? If you measure your weight in kilograms or stones, please use this calculator to convert to pounds:

https://www.thecalculatorsite.com/conversions/common/kg-to-stones-pounds.php

22. What is your height in feet and inches? Please enter numbers only. If you measure your height in meters, please use this calculator to convert to feet and inches:

https://www.thecalculatorsite.com/conversions/common/meters-to-feet-inches.php

23. How old are you?

(write in)

24. What is your marital or relationship status:

-

Single, never married

-

Married

-

Long-term relationship

-

Divorced or separated

-

Widowed

25. What is the highest level of education or degree that you received?

-

Did not attend high school

-

Attended some high school but did not receive a degree

-

High school or graduate equivalency degree (GED)

-

Some college but no degree

-

Associate degree

-

Bachelor degree

-

Graduate degree

26. In what country was your surgery performed?

(write in)

-

If answer is U.S. → go to Q26.

-

If answer is non-U.S. country → skip to Q27.

27. In what state was your surgery performed?

(write in)

28. What best describes your racial / ethnic background? Please check all that apply:

-

American Indian or Alaska native

-

Asian

-

Black or African American

-

Hispanic, Latino or Spanish origin

-

Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander

-

White

-

Other, please specify

29. What type of insurance did you have at the time of your surgery?

-

Private insurance–individual policy, not from employer

-

Private insurance–group policy from employer

-

Medicare with or without a secondary insurance

-

Medicaid

-

National Health Service

-

I don’t know or I don’t remember.

30. Is there any other information you would like the research team to know about your surgery? (optional-write in)

Appendix 2: ASBrS Member Survey

Case Scenario

A 66-year-old man was referred to your clinic with a recent diagnosis of breast cancer. He self-palpated the mass approximately 6 weeks ago. Diagnostic imaging showed a 1.5-cm spiculated mass at the 10:00 position of the right breast 5 cm from the nipple, BIRADS 5. The breast tissue was fatty-replaced on mammogram, and no axillary adenopathy was seen on ultrasound. Ultrasound-guided core biopsy showed a grade 2 invasive ductal carcinoma, ER/PR positive, HER2-neu not overexpressed.

Clinical exam notes a firm, irregular but mobile 2-cm mass in the right upper outer quadrant and no palpable adenopathy. The man is 5'11", weighs 205 lb (BMI, 28.6 kg/m2), and has well-controlled hypertension. He has no family history of breast cancer, and genetic testing was negative for a deleterious mutation or variant of uncertain significance.

Please answer the following questions with your current practice in mind, in other words if you saw this patient today in your clinic, what would you recommend?

1. What is your comfort level recommending breast-conserving surgery to this patient?

-

Very comfortable

-

Somewhat comfortable

-

Not very comfortable

-

Very uncomfortable

2. What concerns (if any) do you have recommending breast-conserving surgery to this patient? Please check all that apply:

-

Inadequate data regarding local recurrence risk

-

Inadequate data regarding safety and effectiveness of radiation therapy in this setting

-

Cosmetic outcome

-

Endocrine therapy compliance

-

No experience performing breast conservation in men

-

I have no concerns about offering breast conservation to men who are appropriate patients.

3. What is your overall impression of the evidence to support breast conservation therapy for male breast cancer patients?

-

There is no evidence.

-

There is limited to weak evidence.

-

There is moderate evidence.

-

There is strong evidence.

4. Have you ever performed breast conserving surgery for a man with breast cancer?

-

Yes

-

No

-

Can’t remember

5. Do you routinely offer breast-conserving surgery to men who are eligible candidates?

-

Yes

-

No

-

Not sure

6. What type of axillary surgery would you recommend for this patient?

-

Upfront axillary lymph node dissection

-

Sentinel node biopsy followed by axillary lymph node dissection if the sentinel node is tumor-positive by intraoperative frozen section

-

Sentinel node biopsy followed by axillary lymph node dissection if the sentinel node is tumor-positive by permanent section

-

Sentinel node biopsy alone even if the sentinel node is tumor positive

-

Other

After some extensive discussion with his family and friends, he decides that he would like to have a mastectomy.

7. Would you offer reconstruction for this patient?

-

No, I do not offer post-mastectomy reconstruction to men.

-

I routinely offer post-mastectomy reconstruction to men.

-

I offer post mastectomy reconstruction only if the patient requested it.

-

I never considered this as an option until this survey.

8. If you would consider reconstruction for this patient, what type of reconstruction would you offer?

-

Implant-based

-

Autologous flap

-

Fat grafting

-

Oncoplastic lumpectomy with contralateral reduction

-

Other, please specify

9. Would you offer this patient nipple sparing mastectomy?

-

I would never offer nipple-sparing mastectomy to a male.

-

I would offer nipple sparing mastectomy only if he were undergoing reconstruction.

-

I would offer nipple sparing mastectomy regardless whether he is undergoing reconstruction.

-

I would offer nipple sparing mastectomy only if he requested it.

10. Would you offer this patient bilateral mastectomy?

-

Yes

-

No

-

Not sure

11. Please rate your level of recommendation for bilateral mastectomy for the following scenarios:

Strong recommendation | Somewhat strong recommendation | Weak recommendation | No recommendation at all | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Any man with newly diagnosed breast cancer | ||||

Men with diagnosis of breast cancer who are confirmed carriers of BRCA pathogenic/likely pathogenic gene mutations | ||||

Men with a diagnosis of breast cancer who are confirmed carriers of moderate-penetrance (CHEK2, ATM, PALB2, CDH1, NF1, STk11, etc) pathogenic/likely pathogenic gene mutations | ||||

Men with a diagnosis of breast cancer who have a suspicious family history of breast cancer in a first-degree relative or multiple relatives | ||||

Men with a diagnosis of breast cancer who are age ≤40 years | ||||

Man with larger breasts for whom a unilateral mastectomy might result in significant asymmetry |

12. How many male breast cancer patients do you treat in an average year?

-

Zero

-

1–5

-

5–10

-

> 10

13. How many patients with breast cancer (male or female) do you treat in an average year?

-

≤ 10

-

11–50

-

51–100

-

101–200

-

201–300

-

≥ 300

14. How long have you been in practice?

-

< 1 year

-

1–5 years

-

6–10 years

-

11–15 years

-

≥ 16 years

15. Did you complete a fellowship in breast surgery or surgical oncology?

-

Yes

-

No

16. In what country do you reside?

-

Dropdown menu of all countries

-

If answer is U.S, go to Q17

-

If answer is non-US country, go to Q18

17. In what state is your practice?

-

Dropdown menu of U.S. states

18. In what country is your practice?

-

Text field to type country

19. Which of the following best describes your primary practice setting?

-

Academic employed/university setting

-

Academic employed/community setting

-

Hospital or health plan employed/community setting

-

Private practice

-

Veterans Administration Hospital or government employed

-

Other

20. What is your sex?

-

Female

-

Male

21. What is your gender preference?

-

Woman

-

Man

-

Non-binary

-

Prefer not to state

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chichura, A., Attai, D.J., Kuchta, K. et al. Male Breast Cancer Patient and Surgeon Experience: The Male WhySurg Study. Ann Surg Oncol 29, 6115–6131 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-022-12135-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-022-12135-6