Abstract

This article employs the six tenets of intersectional research to examine the interconnections of oppression, relationality, complexity, context, deconstruction, and comparison that shape study participants’ experiences. This study was conducted at an after-school STEM program in a poverty-demographic through the lens of intersectionality. This is important because present literature that examines urban demographics and underserved students does not take into consideration the intersections of gender, race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and citizenship as this study reveals. Digital badges, individually awarded to students upon successful completion of 28 small-skill videos while programming in MIT App Inventor, yielded data about persistence through increasingly difficult coding techniques which is a desirable trait for individuals interested in pursuing STEM-focused high schools or professional careers. The results of this study reveal that the intersections of gender, race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and citizenship create a void of power such that children living in this poverty demographic have diminished access to authentic STEM environments and opportunities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

This article recounts a study conducted in the Fall of 2018 at an after-school program (ASP) run by a non-profit organization that serves children of the working poor. The setting is the urban demographic of Paterson, N.J., associated with crime and violence (Schiller 2021), drug and alcohol abuse (State of New Jersey Department of Health 2017), homelessness (NJCDC 2018), poverty (Schiller 2019), food insecurity (NJCDC 2020), teenage pregnancy (State of New Jersey Department of Health 2019), and unstable housing (Balcerzak 2021). While this context is an aggregate of our society’s ills, it is also the home to multi-racial, Hispanic, and refugee groups from Mexico, the Caribbean, Latin America, and the Middle East (Schiller 2019) who are loving family units living in the midst of a mosaic of human vulnerabilities.

The children enrolled at ASP attend surrounding, low-performing, neighborhood schools (State of New Jersey Department of Education 2018). ASP employs tutors who walk to the schools at dismissal to escort the children back to the program’s building. The children assemble in the cafeteria and receive a full, nutritious meal. Following the meal, students work with tutors, led by a group of six certified teachers, to complete homework and to receive additional support to fill the gaps of students’ understanding of math and language arts. If a student enrolls in a special class, such as the Android Inventor program that is the focus of this study, then they gather their belongings and report to the computer lab to complete their homework instead of remaining in the cafeteria. The corresponding author and college freshman science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) Intern of this study were on hand to assist our 10 female and 7 male, multi-racial, multi-ethnic study participants with their fourth through seventh grade homework before the students resumed their work on an Android mobile dice game application programmed using MIT App Inventor. The research included a parent demographic survey at the beginning of the study that reported income at or below the poverty level and identified the participants self-reporting as, multi-racial, Hispanic, and Middle Eastern. To round out the picture of the children’s care, ASP dismisses all students to parents, guardians, or designated family members at a time when dusk is approaching and the need to walk home in the waning daylight is a necessity.

This article examines our study participants’ perceptions about computer programming in a STEM-focused learning opportunity at ASP through the lens of intersectionality. The methods of intersectional research provide the framework to examine the array of intersecting social systems that shape our participants’ experiences.

Theoretical framework

Intersectionality is a pivotal sociological framework that provides researchers with a lens to study the mosaic of unique, intersecting attributes of a person’s life that frame their lived experiences. In her work regarding intellectual activism, Patricia Hill Collins (2013) notes that previous practitioners studying race, class, and gender essentially siloed these subfields such that their research became unmindful of the complex interrelationships of these social constructs. Hill Collins contends that intersectionality moves beyond this triad of social phenomena to consider additional categories such as ethnicity, age, religion, nation, and sexuality (p. 94).

Columbia University law professor Kimberle Crenshaw, credited with the coinage of the term, defines intersectionality as a lens through which society can view where power comes from, collides, intersects, and interlocks (Cho et al. 2013). In an article in the Stanford Law Review, Crenshaw crystalizes the focus on social power as the force that works to marginalize or exclude those who are different (Crenshaw 1991).

Based on the ASP poverty demographic and the enrollment of multi-racial, multi-ethnic male and female participants, the article deals with two overarching research questions:

-

1.

What impact do the intersections of gender, race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and citizenship status have on participants’ attitudes toward a computer programming, STEM-focused learning opportunity at ASP?

-

2.

How does gender influence participants’ persistence through increasingly rigorous programming skills?

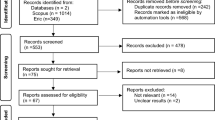

Methods and data

This study employed three measures to evaluate students’ attitudes toward a STEM-focused learning opportunity during a 28-day Android Inventor computer programming opportunity. The first measure was the S-STEM survey (Unfried et al. 2015) that collected pre- and post-study data regarding students’ attitudes toward the component disciplines of science, technology, engineering, math, and 21st-century skills. The study team chose the S-STEM measure because the survey authors documented high Cronbach’s Alpha reliability levels, content validity, and construct validity of the instrument (Friday Institute for Educational Innovation 2012). Additionally, this research centered on students’ attitudes toward STEM subjects and career interests which the S-STEM survey supports.

The second measure quantified digital badges awarded after the successful completion of 28 small-skill videos that individual students completed at their own pace to create a dice game on the MIT App Inventor programming platform. The sequentially numbered digital badges served to quantify students’ progress and level of persistence throughout the study. The digital badges were important to the study because they provided the study team with an additional measure to evaluate the influence of gender through increasingly rigorous programming skills accomplished by the participants. Nine beginner badges, 12 intermediate, and seven advanced badges served as tangible, quantifiable evidence of students’ progress.

The quantitative data recorded in the S-STEM survey and digital badges could not provide generalizability because of the inevitably small sample size of 17 students out of the approximately 100 students enrolled at ASP during any school year. The addition of interviews and focus group data align with Guba’s (1981) encouragement of the term transferability rather than generalizability to stage future re-enactments of the study. Krefting’s (1991) asserts that generalizability is irrelevant in qualitative research because the strength of qualitative inquiry resides in naturalistic settings. Transferability describes a goodness of fit among two contexts that will be determined by a future researcher to re-enact the study (Guba 1981). Therefore, the study team chose to enrich the data by embracing a mixed-methods approach. An additional qualitative measure recorded student interviews and focus group data collected at the end of the program during a one-day Hack-A-Thon event that queried students’ perceptions about STEM and future career aspirations. The study team used a password-protected otter.ai application to record and transcribe interview and focus group data. Additionally, the team typed notes into a password-protected Evernote journal as a backup to the otter.ai transcription. Despite the small sample size, it was of the utmost importance to the study team to query participants’ attitudes toward STEM and future career aspirations to contribute to the research that studies children of the working poor who could benefit from future STEM careers to lift them out of poverty.

Procedure

The recruitment of study participants aligned with an August 2018 Back to School Boutique conducted by ASP to offer students school supplies and backpacks for the upcoming school year. The research team attended the event to meet with families to describe the upcoming Android Inventor study that offered instruction about how to program a mobile dice game using MIT App Inventor. Parents completed consent forms and a demographic survey. Students completed assent forms. All Johns Hopkins University Homewood IRB-approved forms and surveys offered both English and Spanish versions. Other than the initial consenting of their students into the study, the parents did not attend nor interact with the study at ASP.

Males predominantly enrolled in previous after-school STEM course offerings conducted by the corresponding author with male to female ratios of 9:3, 10:4, 12:1, and 11:4. The study team purposefully recruited female students to this study to generate data to inform the focus of the research questions regarding intersectionality, gender, and persistence through increasingly rigorous programming skills.

The students completed the S-STEM survey (Unfried et al. 2015) prior to the Android Inventor program and directly after completing the study. Participants attended the Android Inventor program for 23 school days during the month of October 2018 and a one-day group Hackathon on the first Saturday of November 2018. During the 23 school days, students reported to the ASP computer room, completed all their homework, and then viewed 28 consecutive small-skill videos recorded by the corresponding author at their own pace using earbuds to complete the dice game on MIT App Inventor. Students accessed a Google classroom platform that contained nine beginner, 12 intermediate, and seven advanced skill videos. Participants demonstrated their working program to a member of the study team after each completed video and received one of 28 consecutively numbered digital badges on their individual Padlet to record their progress (see Fig. 1).

The participants convened at a one-day Hackathon on the first Saturday of November 2018 to work in pairs on new MIT App Inventor applications to apply their recently acquired programming skills to unique applications. At the end of the Hackathon, the participants convened in a focus group to offer feedback about their experiences in programming the dice game and new applications during the Hackathon event.

Literature review

Similar studies focusing on programming in after-school urban demographics include Newton et al. (2020) who enrolled 93 third- through fifth-grade students of 60% male and 40% female predominantly African-American participants to receive 20 h of programming instruction over a ten-week period during a STEM summer camp offered for four years. The Newton et al. (2020) team also conducted a mixed-methods study that included a survey and a random sampling focus group of 14 females to 13 males to query students’ attitudes toward game design that aligns with the present ASP study. The Newton et al. (2020) participants programmed a maze game using the AgentCubes game design website (AgentCubes 2022). The quantitative results of the Newton et al. (2020) game design portion of their study claim no significant changes from pre- to post-survey regarding video gaming, computer use, or attitudes toward engineering/technology and a significant change pre- to post- about computer gaming. The qualitative results regarding game design of Newton et al. (2020) study revealed that students appreciated the agency to create unique games; however, they reported a high level of challenge that signaled the need for additional supports for component programming tasks.

The Newton et al. (2020) study took place over a four-year period at a local university in an urban setting without mention of the SES of the participants’ families as compared to the ASP participants whose parents identify as living at or below the poverty level. The ASP study employed consecutive, small-skill videos to instruct students about programming skills rather than direct instruction. The ASP students reviewed their developing program with the study team to receive individualized supports to clarify skills before moving onto the next video. The ASP small-skill videos provided benefits such as self-paced instruction with an opportunity to rewind, review, receive clarification, and resume without the need to wait for whole-class instruction.

A second example in the literature regarding an after-school program in an urban environment is Vakil (2014) who elaborates on the framework of critical pedagogy that values solidarity, social responsibility, and service to the common good (Freire 1970). Vakil (2014) makes socio-political connections to a computational activity using Google App Inventor, a forerunner of the Android mobile app employed during ASP, before MIT took over the maintenance of this software (Kincaid 2011). The focus of the Vakil (2014) study observed behavioral, emotional, and cognitive engagement of marginalized students in the urban demographic of Oakland California through a critical pedagogical approach. Vakil’s (2014) study enrolled four African-American high-school participants, three female and one male. The procedure for direct instruction occurred twice a week over one semester with three weekend workshops. Data were collected through an ethnographic approach to observe participants’ level of engagement, direct interaction with participants, and coding of field notes in a solely qualitative approach. The participants of the Vakil (2014) study developed an application to inform peers about after-school programs and community resources through direct instruction and online tutorials. The Vakil (2014) study revealed high levels of cognitive development through increasingly advanced programming skills; however, the emotionally engaging social topic did not transfer to cognitive engagement for all participants.

The similarities of the Vakil (2014) to the ASP study align with the 3:1 and 10:7 predominantly female to male ratio, small sample size, the support of a social framework such as critical pedagogy or intersectionality, the use of App Inventor as the programming platform, and the focus on participant persistence through increasingly advanced programming skills. While the Vakil (2014) study did not specifically mention their participants SES, the student’s qualitative data that mention the topic obesity of urban children due to a lack of healthy food choices and lack of programming opportunities during school denote a similar demographic to ASP.

A third study conducted by Calandra et al. (2021) enrolled thirty-two predominantly African-American or multi-racial middle-school students, 16 females and 16 males, to examine engagement to learn MIT App Inventor during an after-school program in an urban school district in the southeast United States. The Calandra et al. (2020) mixed-methods study employed a programming quiz and quantified completed applications to conclude that there is a linear relation between quiz scores and the number of apps completed by participants. Calandra and colleagues (2020) employed the computational thinking (Papert 1980) construct to query how a series of MIT App Inventor-coding activities influenced the participants’ learning process. The Calandra et al., (2020) study does not mention the students’ SES nor does it report on the outcomes of number of apps and accuracy of quiz results based on gender.

The similarities of the Calandra et al., (2020) to the ASP study align with an urban demographic of predominantly students of color and the use of MIT App Inventor as the platform to learn programming skills during an after-school program. The two studies depart in similarities in that the ASP study frames the students’ progress through the lens of intersectionality and takes into consideration the participants’ lived experiences and gender as an impact to the persistence through increasingly advanced programming skills.

The National Center for Women and Information Technology (2020) indicates that only 3% of the 2020 computing workforce were African-American women, 7% were Asian, 2% were Hispanic, and 13% White for a total of 25% of women employed in this field. The literature supports the need to provide females with STEM course opportunities beginning in middle school and transitioning into high school to support their confidence in rigorous, math-based courses (Dare & Roehrig 2016; Lofgran et al. 2015; Yeager et al. 2016).

The ASP study will elaborate on the influence of intersectionality on the participants’ outcomes that departs from the binary, male and female attributes in the discussion section of this article.

Results

Quantitative results

The most compelling observation during data analysis was the quantified digital badges, which revealed that males achieved 54% of the possible 28 digital badges to 36% of the female participants (see Table 1). The females attained an average of 10 badges, while the males collected an average of 15 badges (see Table 1). Only two males persisted in the Advanced Programming skills level, with one male completing all 28 video lessons (see Table 1). The study team awarded up to twenty-eight consecutively numbered badges on individual student’s Padlet to provide the students and study team with tangible evidence of their progress through beginner, intermediate, and advanced programming skill levels (see Fig. 1).

S-STEM survey subscales

The S-STEM survey (Friday Institute for Educational Innovation 2012) queried students’ attitudes toward the component disciplines of STEM:

-

An example of a math-attitude question is, “I am the type of student who does well in math.”

-

A question regarding science attitude is, “I expect to use science when I get out of school.”

-

An example of an Engineering and Technology question is, “I am interested in what makes machines work.”

-

STEM belonging was quantitatively proxied by 21st Century Learning, the 4th subscale on the S-STEM. An example of a 21st Century Learning question is, “I respect all children my age even if they are different than me.”

The corresponding author created a variable pre- and post- study that contained the mean of the S-STEM attitude survey categories: math, science, engineering and technology, and 21st-century skills. See Tables 2 and 3 for overall STEM attitudes. Participants hovered in between a “3 – neither agree nor disagree” and a “4 – agree” regarding pre- and post-study mean of attitudes toward STEM. The study team believed that it was important to reveal students’ attitudes toward STEM as an integrated field of the component subjects of science, technology, engineering, and math because the Paterson high schools and surrounding town regional schools provide STEM academies to which these middle-school students could apply. As in the Valkil (2014) Oakland, California study in the literature review, participants must intentionally opt into a STEM-focused high school. Additionally, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (Zilberman 2021) predicts that STEM employment in the 2019–2029 decade will exhibit strong growth, especially in computer occupations which could help lift these families out of poverty.

Interest in agentic careers—quantitative

The term agentic denotes agency or power where males typically choose rigorous, math-intensive careers with greater advancement opportunities (Eagly 2013). Even when employers offer females agentic jobs with a favorable work–life balance to accommodate family responsibilities, women still tend to choose communal, helping others” careers (Barth et al. 2015). Since intersectionality considers where “power” resides in the lived experiences of the participants, the study team thought that it was important to query this group about agentic careers to analyze the females’ attitudes toward more rigorous careers such as computer science.

The children in the Paterson School District never participate in a “career day” at school as do middle and upper socioeconomic status (SES) students (J. Egger, personal conversation, July 3, 2021). The study team believes that the survey questions that introduce career descriptions are an important step toward revealing future, well-paying jobs for children living in poverty. The corresponding author created a variable that contained student’s interest in the math-intensive, agentic jobs. Pre- and post-survey scores for agentic careers are found in Tables 4 and 5, respectively. The survey results regarding interest in agentic careers revealed that all participants hovered between “2-not so interested” and “3-interested.” Female participants’ mean score, found in Table 6, regarding agentic careers was 2.70, hovering just below interested. Male participants’ mean score about these math-intensive careers was 3.52, hovering between “3-interested” and “4-very interested” (see Table 6).

To specifically analyze the students’ individual attitudes toward computer science, math, engineering, and technology by gender the study team created a case summary analysis of merged pre- and post-survey mean data by anonymized participant ID. Resulting Table 6 reveals that six out of seven males and four out of 10 females were very interested in computer science. One out of seven males and three out of 10 females were interested. Two females were not so interested in computer science, and one female was not at all interested (see Table 6). Regarding math, the mean Likert score revealed that males hovered just below agreement that they do well in math at 3.98 while females revealed a 3.54 which is approximately halfway between a neutral neither agree nor disagree about math abilities and a 4 that denotes agreement (see Table 6).

The engineering and technology data (see Table 6) revealed that one male 5 = strongly agrees that he aligns with this field with one male indicating a 4 – agree. Four out of 10 females indicate agreement with their engineering and technology capabilities. The mean science score for females was 2.80 that show most females lack of alignment with science with only one female indicating agreement with her science capabilities. Three out of seven males indicated alignment with science while the remaining three hovered around neither agree nor disagree with science capabilities (see Table 6).

Qualitative results

Figure 2 contains the IRB-approved interview and focus group questions enacted by the study team. To provide intercoder reliability (Creswell & Plano-Clark, 2011), the corresponding author created copies of the password-protected Evernote interview and focus group journal for the team to code independently before discussing the emerging themes depicted in Table 7. The team met once a week from November 2018 to January 2019 to conduct iterations to agree upon themes emerging from the transcripts. The study team took a grounded theory, inductive approach to coding the transcripts that emerged from the data instead of an a priori approach that looks for specific keywords (Bryant & Charmaz 2007).

Math attitudes—qualitative

The qualitative data revealed some students admit that they find the subject difficult while others shared that they like math and receive good grades. Inventor 17, the female participant who was the first to complete the beginner Android Inventor small-skill videos, indicated that she wants more math classes in school. When asked to describe his math class, Inventor 12 indicated that the teacher tells them things, the class writes them down, and then they study. The frequency of this type of comment led the study team to develop a code to indicate well-structured problems (see Table 7) with one right answer, rather than ill-structured problems that require strategic thinking (Kirkley 2003) in math classes. This is important to the ASP study because the participants developed new MIT App Inventor programs through multiple possible approaches during the Hackathon event.

Engineering and technology attitudes—qualitative

The students expressed that they had little experience with programming before Android Inventor. The participants did not mention any other outside computer programming influences. Concerning engineering, the students referred to experiments in science class as their opportunities to engineer or build something. Inventor 25, a male student who indicated a “5-strongly agree” regarding his interest in engineering, mentioned that his only use of computers in school is to learn how to type online. Numerous students also mentioned typing programs as their only exposure to computers in school. This emerging theme led the study team to develop the code “limited exposure to technology (see Table 7). Most students mentioned games when asked about technology. The Director of Education at ASP confirmed that, despite the poverty demographic, most students possess a mobile phone device which families consider a necessity to communicate with their children (J. Egger, personal conversation, July 3, 2021). The students frequently play games on their mobile device or on the computers in the lab. Regarding the MIT App Inventor platform, students responded positively concerning technology, using terms such as “amazing” and “fun,” and wishing for more programs like Android Inventor.

STEM acronym—qualitative

During the study, the researcher team did not elaborate on the meaning of the STEM acronym or that males were typically associated with technology and programming. Interviews revealed that only one of the 17 students knew the component disciplines of the STEM acronym. This student shared that she learned the meaning of STEM by taking the S-STEM survey. The students in this program did not have any preconceived ideas about STEM environments. As indicated in the previous sections, it is important for the participants to know about STEM opportunities for future high-school enrollment in STEM-focused “academies” and future, prevalent, well-paying careers (Zilberman 2021). Therefore, the study team coded “STEM Blinders” (see Table 7) to indicate a lack of focus on these opportunities.

Agentic careers—qualitative

Of the students who had an idea of a future career, two girls and two boys named agentic, rigorous, and math-intensive careers, in computers, programming, science, or engineering. Other careers named by the students included owning a baking business, modeling, acting, teaching, and law enforcement. As described in the introduction of this article, the participants are children of the working poor. Their role models are hard working parents and guardians working in low-paying service and labor industries. Participants base their career expectations on who they encounter on a day-to-day basis such as teachers, police officers, celebrities in print or social media, or local store owners. The students in this demographic lack the STEM role models available to the middle and upper-SES groups. As confirmed in the literature, role models play a pivotal role in helping students, especially females, persist in STEM courses and careers (Aguar et al. 2016; Allen- Ramdial & Campbell, 2014; Herrmann et al. 2016).

Discussion

The intersectional methodology posited by Misra and colleagues (2021) suggests six tenets of intersectionality to help researchers analyze data through the interconnection of comparison, oppression, relationality, complexity, context, and deconstruction. The following sections delineate these interconnections as reflected in the context of this study.

Comparison

Misra et al. (2021) note that, while intersectionality considers an aggregate of socially constructed dimensions of difference, researchers can compare a subset of dimensions to support the questions that underpin a study. The research questions that support the analysis of collected data examines the intersections of gender, race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and citizenship status that are most salient to compare the interlocking, colliding nexus of power. This study examines participants’ attitudes toward an Android Inventor programming class in the STEM education initiatives of ASP located in a poverty demographic. Through the lens of intersectionality, the study team considered how the absence of curriculum such as computer programming classes impacts children in this marginalized group who often attend schools without these types of resources. The salient differences between upper-SES and poverty-demographic school districts become obvious in the areas of teacher retention and quality of instruction (Whipp & Geronime 2017). The study team member who is the Director of Education at ASP made the following observations regarding the technology, math, and science instruction in the neighboring, low-performing schools:

-

Students have minimal computer experience and standardized tests remain paper based.

-

Urban districts, such as Paterson, struggle to retain teachers. One of the local schools that dismisses students to walk with tutors after school to ASP does not have consistent math or science teachers. The administration sends students who were not assigned a math or science teacher to the auditorium to wait until their next scheduled class.

-

Children often miss school to accompany parents on appointments to translate for them from their native language to English.

In 1991, the State of New Jersey took over the full control and oversight of the Paterson School District due to the failure of the school district to meet the New Jersey Quality Single Accountability Continuum performance criteria of instruction and program, personnel, fiscal management, operations, and governance (State of New Jersey Department of Education 2018). It was not until 27 years later, and in the year of this study in 2018 that the State of New Jersey returned the oversight of instruction and program to the Paterson School District (State of New Jersey Department of Education 2018).

Oppression

Van Wormer (2015) comments that social scientists’ previous definition of oppression, as the placement of severe restrictions on an individual group or institution, does not go far enough to consider the intersections of multiple roles, identities, and key characteristics that move past neatly packaged, dichotomous, dominant versus subordinate groups. Misra et al. (2021) recognize oppression as the relationship between power and inequality. The students in this study experience multiple layers of oppression as documented, partially documented, or “alien” levels of citizenship. Immigration law in the United States uses four categories to construct “alien” status: race, ethnicity, gender, and class (Romero 2008). Most Paterson N.J. immigrant families arrive in the United States to escape the corruption and violence in their native countries. Oftentimes, one parent will travel ahead of a spouse, partner, or children to live with friends, extended family, or friends who offer shelter in already crowded living conditions. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents, present in the ASP neighborhoods, follow immigrant communities based on non-white physical appearance as a proxy for citizenship (Romero 2008). The impact on children whose parents, guardians, or primary caregivers are detained by ICE is profound and increases absenteeism at school (Sanchez 2019).

Relationality

The concept of relationality in intersectionality is to reveal that the oppression of one group is intertwined with the privilege of others. The organization that runs ASP dedicates its programs to women and their children. The women who enroll their students at ASP work in service, or local manufacturing jobs. Those women who work as cleaning ladies, or home health aides, take mass transportation to the center of higher socioeconomic status towns where they either walk to their predominantly white employers’ homes or are picked up at the train or bus stations by someone from the household. These women work for minimum wage that requires them to rely on the food and clothing pantries provided by organizations such as ASP. The privilege of having one’s house cleaned or an elderly parent cared for at home is an example of the oppression of the women-of-color in Paterson, N.J.

In her essay regarding transformation of silence, Audre Lorde (2012) writes about the concept of Ujima, collective work, and responsibility. Ujima is celebrated during the Feast of Kwanza, the African-American festival of the harvest. The significance of Ujima is the collective decision of a community to recognize and solve their problems together. The ASP is an example of the collective work of women to recognize the need to enroll their students in a program that provides safety, nourishment, education, food, and clothing, among many other fundamental needs to sustain their families.

Complexity

The complex nature of multiple levels of difference is the nexus of intersectional research such that race, gender, class, and citizenship identities are interwoven. In her talk about Oppression Olympics, Dr. Angie-Marie Hancock (Rutgers University, 2009) reminds us to move away from binary viewpoints such as male versus female, to remedy an issue that benefits everyone no matter their race, ethnicity, gender, or citizenship status. A component of the Oppression Olympics is willful blindness where, for instance, the second wave of feminism does not consider how women’s opportunities and their class privilege do not extend to females of lower socioeconomic groups (Rutgers University, 2009).

Adding to the complex nature of the lives of students in this study is the concepts of concerted cultivation and natural growth posited by Lareau (2011) in her ethnographic study of class, race, and family life. Concerted cultivation is the upper-SES practice of parent-directed child rearing where a sense of entitlement and privilege ensues regarding education and making those around them bend to their needs. In contrast, lower SES children in Lareau’s study experience natural growth with a higher degree of child autonomy exists when parents take a hands-off approach to allow schools to direct learning and their children to select their free-time activities away from adults. The context of the ASP is neither concertedly cultivated nor is it naturally grown. As stated in the introduction of this article, ASP serves children of the working poor. The parents and extended family must work several jobs to survive and rely on the ASP food pantry to supplement putting food on the table. The participants of this study cannot play freely on the streets after school because of the multitude of dangers present. This study team suggests that the complex nature of race, class, gender, and citizenship warrants the new moniker of cultivated haven such that parents of the working poor cultivate a safe haven for their children after school to align them with supportive adults who bridge the gaps of safety, education, and opportunity.

An example of cultivated haven within the group of participants of this study are two cousins, Inventors 2 and 17. The cousins live together with their parents at the same address and come from a stable home environment supported by multiple programs at ASP (J. Egger, personal conversation, July 3, 2021). Inventor 2, a male, described STEM as “a part of a tree” when interviewed by the study team. Inventor 17, a female, and the first to earn the nine beginner digital badges, indicated that she wanted to be good at math to help her future children with homework. When the research team asked Inventor 17 about the meaning of STEM, she indicated that she did not know. When asked why they attended the Android Inventor program, Inventor 17 said, “My Mom forced me to sign up.” Inventor 2 indicated his reason as, “I like technology.”

Context

Intersectional researchers take context beyond general descriptive terms to highlight the intersections where disadvantage and privilege unfold (Misra et al. 2021). The 17 students in the Android Inventor study represented 14.5% of the 117 students enrolled in ASP during 2018–2019 (Oasis 2019). During 2018–2019, ASP provided women and children 65,000 meals, distributed 2,500 food bags, 3,000 clothing bags, and 100,000 diapers. The revenue sources to fund the ASP initiatives are 41% individuals followed by 34% foundations, 13% corporations, 9% non-profits, and lastly, 3% government (Oasis 2020). When Inventor 25’s mom arrived at dismissal to pick up her four children at ASP, the study team observed that she and the children were consistently carrying bags of food to bring home.

Deconstruction

Misra et al. (2021) suggest that the intersectional researcher remain attentive in their analysis of the malleability of categories to consider how oppression itself can influence traditional interpretations of gender-based attitudes in environments that differ by race and ethnicity. For instance, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2021) reveals that only 25.2% of the computing workforce in 2020 are women. Of the men and women employed in computer and mathematical occupations, 65.4% are white, 9.1% are African American, 23% are Asian, and 8.4% are Hispanic (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2021). The intersectional researcher studying differences in opportunities for technology students must consider the impact of race and in the computer and mathematical occupations.

Underpinning this lack of multi-racial, multi-ethnic females in technology is that four females’ survey results indicated that they are 4—very interested in computer science and three additional females are 3—interested (See Table 6). Yet only one of the participants of this study knew the meaning of the STEM acronym and that this knowledge came from the pre-test S-STEM survey. This is important because these students can actively pursue enrollment into a STEM-focused Paterson school district or regional high school to continue their technology education. When asked during the post-study interviews, “What is STEM?” sixteen of the students replied, “A part of a tree,” or “I don’t know.” The students’ elementary and middle-school school district does not offer technology courses but does offer STEM-focused high schools and regional schools to which the participants can apply. When surveyed about the component disciplines of STEM, the students indicated “4-very interested” and “3-interested” for computer science. Qualitatively, students of both genders expressed enthusiastic interest in more programming courses like the Android Inventor program.

Survey data on gender, socioeconomic status, race, ethnicity, and grade level were all collected as contributing factors in this study. The study did not collect information on immigration status as this is a sensitive topic. Had the sample size been large enough, the researchers would test the collected variables as moderators. However, even without statistical moderation, the effect of gender was apparent insofar as males’ achievement of digital badges in the persistence through increasingly rigorous programming skills.

The result that students were simply unaware of STEM as an integrated field of study highlights the effects of socioeconomic status, given that the sample was from a poverty demographic. The researchers presumed that students would know that STEM is an integrated field of study; however, none of them did, either not knowing or referring to a tree’s stem. One exception emerged when a fourth-grade girl revealed that she learned the definition of STEM from the survey instrument. In the analysis, this gave rise to the qualitative coding of “STEM Blinders.” The blinders exist because of a void in school and home environments to provide the participants of this study with knowledge of STEM as an integrated field of study prevalent in middle and upper-SES demographics. This study departs from others that center on “urban” demographics and that enroll students of color without taking into consideration the impact of poverty on students’ opportunities to learn.

Conclusion

To answer the first research question regarding the impact that the intersections of gender, race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and citizenship status have on participants’ attitudes toward a computer programming, STEM-focused learning opportunity at ASP, the study team concludes the following. A siloed approach to these socially constructed intersections typically explains the lack of women and minorities in computer and mathematical careers as stereotype threat (Cheryan et al. 2017; Danaher & Crandall 2008; Deemer et al. 2014). Blickenstaff (2005) labels the exit of women in STEM fields as a leaky pipeline that yields membership in a STEM-focused group to those more powerful such as White males without considering the impact of socioeconomic status. Eagly (2013) documents the power dynamics of agentic, math-intensive careers with opportunities for advancement as denoting “agency” or “power,” and predominantly male dominated. Both male and female participants of this study who attend low-performing schools with sporadic math and science classes and little access to technology are left to navigate toward concerted havens such as ASP to take part in authentic STEM programs such as Android Inventor that could lead to enrollment in STEM-focused high schools and careers that will make up more than two-thirds of projected new jobs (Gallup 2020). The study team concluded that the intersections of gender, race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and immigration status significantly impacted participants’ prior knowledge of STEM as an integrated field of study.

To answer the second research question regarding the influence of gender on participants’ persistence through increasingly rigorous programming skills, the study team offers the following analysis. The digital badges earned by the males in this study outpaced the females by 18% (see Table 8). During our study team discussions, the potential reasons for this lack of persistence by females in programming could rest among the additional factor of oppression placed on Hispanic females in this demographic. As corroborated by the Latina STEM Intern of this study, there is a dominant male influence in the Hispanic family. Galanti (2003) presents the term machismo as a generalization, not a stereotype, where males are the supporting patriarchs of the family, and women hold traditional roles as housewife and mother. As a female raised by a single Mom, our STEM intern escaped the oppression of machismo, and her mom encouraged her to pursue her interests in technology. Inventor 17, the first participant to earn a beginner certificate in the Android Inventor program, shared that it was important for her to learn math to help her future children with their homework. Kayumova and colleagues (2015) support this assertion regarding the additional oppression placed by families on Latina daughters who can opt into immediate, low-skill work instead of opportunities afforded through meaningful education. Perhaps the female participants in this study did not see programming as a skill that was usable in their expected future roles.

The results of this study reveal that the intersections of gender, race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and citizenship create a void of power such that children living in this poverty demographic have diminished access to authentic STEM environments and opportunities.

Data availability

Open Science Framework view link containing anonymized survey, interview, and focus group data: https://osf.io/xq49u/?view_only=c065c8c8b1334b59886244d10dad0563

Code availability

The MIT App Inventor custom code is available upon request to the corresponding author.

References

AgentCubes (2022) Agentsheets.com. https://agentsheets.com/

Aguar K, Arabnia HR, Gutierrez JB, Potter WD, Taha TR (2016) Making CS Inclusive: An Overview of Efforts to Expand and Diversify CS Education. In: 2016 International Conference on Computational Science and Computational Intelligence (CSCI) (pp. 321–326). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/CSCI.2016.0067

Allen-Ramdial SA, Campbell AG (2014) Reimagining the pipeline: advancing STEM diversity, persistence, and success. Bioscience 64(7):612–618. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biu076

Balcerzak A (2021, September 21) Annual count of homeless people in NJ highlights vast racial disparities. North Jersey Media Group; NorthJersey.com. https://www.northjersey.com/story/news/2021/09/21/homeless-new-jersey-count-covid-pandemic-racial/5795766001/

Barth J, Guadagno R, Rice L, Eno C, Minney J (2015) Untangling life goals and occupational stereotypes in men’s and women’s career interest. Sex Roles 73(11):502–518. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-015-0537-2

Blickenstaff JC (2005) Women and science careers: Leaky pipeline or gender filter? Gend Educ 17(4):369–386. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540250500145072

Bryant A, Charmaz K (2007) The Sage handbook of grounded theory. Sage

Calandra B, Renken M, Cohen JD, Hicks T, Ketenci T (2021) An examination of a group of middle school students’ engagement during a series of afterschool computing activities in an urban school district. TechTrends 65(1):17–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-020-00557-6

Cheryan S, Ziegler SA, Montoya AK, Jiang L (2017) Why are some STEM fields more gender balanced than others? Psychol Bull 143(1):1–35. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000052

Cho S, Crenshaw KW, McCall L (2013) Toward a field of intersectionality studies: theory, applications, and praxis. Signs 38(4):785–810. https://doi.org/10.1086/669608

Crenshaw K (1991) Mapping the margins: identity politics, intersectionality, and violence against women. Stanford Law Rev 43(6):1241–1299. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039

Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL (2011) Designing and conducting mixed methods research. SAGE

Danaher K, Crandall C (2008) Stereotype threat in applied settings re-examined. J Appl Soc Psychol 38(6):1639–1655. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2008.00362.x

Dare E, Roehrig G (2016) “If I had to do it, then I would”: understanding early middle school students’ perceptions. Phys Rev Phys Educ Res 12(2):020117–020119. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevPhysEducRes.12.020117

Deemer ED, Thoman DB, Chase JP, Smith JL (2014) Feeling the threat: stereotype threat as a contextual barrier to women’s science career choice intentions. J Career Dev 41(2):141. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845313483003

Eagly AH (2013) Sex differences in social behavior. Taylor and Francis, New York

Freire P (1970) Pedagogy of the oppressed. Herder and Herder, New York

Friday Institute for Educational Innovation (2012) Middle and high school STEM-student survey. Friday Institute for Educational Innovation. https://www.fi.ncsu.edu/resources/student-attitudes-toward-stem-s-stem-survey-tips-for-using-your-data/

Galanti G (2003) The hispanic family and male-female relationships: an overview. J Transcult Nursing 14(3):180–185. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659603014003004

Gallup (2020) Current Perspectives and Continuing Challenges in Computer Science Education in U.S. K-12 Schools. Gallup. https://services.google.com/fh/files/misc/computer-science-education-in-us-k12schools-2020-report.pdf

Guba EG (1981) Criteria for assessing the trustworthiness of naturalistic inquiries. Educ Commun Technol J 29(2):75. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02766777

Herrmann SD, Adelman RM, Bodford JE, Graudejus O, Okun MA, Kwan VSY (2016) The effects of a female role model on academic performance and persistence of women in STEM courses. Grantee Submission 38(5):258–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973533.2016.1209757

Hill Collins P (2013) On intellectual activism. Temple University Press, Philadelphia

Kayumova S, Karsli E, Allexsaht-Snider M, Buxton C (2015) Latina mothers and daughters: ways of knowing, being, and becoming in the context of bilingual family science workshops. Anthropol Educ Q 46(3):260–276. https://doi.org/10.1111/aeq.12106

Kincaid J (2011, August 16) Google Gives Android App Inventor A New Home At MIT Media Lab. TechCrunch; TechCrunch. https://techcrunch.com/2011/08/16/google-gives-android-app-inventor-a-new-home-at-mit-media-lab/

Kirkley J (2003) Principles for Teaching Problem Solving. (Technical Paper #4). Indiana: PLATO Learning. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.564.9218&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Krefting L (1991) Rigor in qualitative research: the assessment of trustworthiness. Am J Occup Ther 45(3):214–222. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.45.3.214

Lareau A (2011) Unequal childhoods: class, race, and family life, with an update a decade later. University of California Press

Lofgran BB, Smith LK, Whiting EF (2015) Science self-efficacy and school transitions: elementary school to middle school, middle school to high school. Sch Sci Math 115(7):366–376. https://doi.org/10.1111/ssm.12139

Lorde A (2012) Sister outsider: essays and speeches. Crossing Press, New York

Misra J, Curington CV, Green VM (2021) Methods of intersectional research. Sociol Spectr 41(1):9–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/02732173.2020.1791772

National Center for Women and Information Technology (2021, March 25) By the Numbers. Ncwit.org. https://ncwit.org/resource/bythenumbers/

Newton KJ, Leonard J, Buss A, Wright CG, Barnes-Johnson J (2020) Informal STEM: learning with robotics and game design in an urban context. J Res Technol Educ 52(2):129–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2020.1713263

NJCDC (2018) Helping Count Paterson’s Homeless. Njcdc.org. https://www.njcdc.org/news-events/!/index.php?Helping-Count-Paterson-s-Homeless-205

NJCDC (2020) NJCDC Helps Feed 100 Families-in-Need. Njcdc.org. https://www.njcdc.org/news-events/!/index.php?305

Oasis (2019) Oasis 2018/2019 Annual Report (Rep. No. 2018/2019). Retrieved October 10, 2021, from Oasis website: https://s3.amazonaws.com/media.cloversites.com/3a/3afdf930-4a3a-47d3-9b03-2fb1ccfcd3ac/documents/Final_Annual_Report_FY19.pdf

Oasis (2020) Oasis 2019/2020 Annual Report (Rep. No. 2019/2020). Retrieved October 10, 2021, from Oasis website: https://s3.amazonaws.com/media.cloversites.com/3a/3afdf930-4a3a-47d3-9b03-2fb1ccfcd3ac/documents/Annual_Report_2020_Final_Final.pdf

Papert S (1980) Mindstorms: children, computers, and powerful ideas. Basic Books

Romero M (2008) The inclusion of citizenship status in intersectionality: what immigration raids tells us about mixed-status families, the state and assimilation. Int J Sociol Fam 34(2):131–152

Rutgers University (2009, June 23) Dr. Ange-Marie Hancock-Beyond the oppression Olympics [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5lvomJnkPq4&t=9s

Sanchez R (2019) Their first day of school turned into a nightmare after record immigration raids. cnn.com; CNN. https://www.cnn.com/interactive/2019/08/us/mississippi-ice-raids-cnnphotos/index.html

Schiller A (2019) Paterson, NJ Demographic Data. Neighborhoodscout.com; NeighborhoodScout. https://www.neighborhoodscout.com/nj/paterson/demographics

Schiller A (2021) Paterson, NJ Crime Rates. Neighborhoodscout.com; NeighborhoodScout. https://www.neighborhoodscout.com/nj/paterson/crime

State of New Jersey Department of Health (2017) New Jersey Drug and Alcohol Abuse Treatment Substance Abuse Overview 2017 Passaic County. https://www.state.nj.us/humanservices/dmhas/publications/statistical/Substance%20Abuse%20Overview/2017/Pas.pdf

State of New Jersey Department of Health (2019) NJSHAD - Community Health Highlights Report Indicator Page - Passaic, Teen Birth Rates. State.nj.us. https://www-doh.state.nj.us/doh-shad/community/highlight/profile/AgeSpecBirthRate.Co1517/GeoCnty/16.html

State of New Jersey Department of Education (2018) Transition Plan for the Return of Local Control to Paterson Public Schools. http://www.paterson.k12.nj.us/PDF/18-19/2%20Year%20Transitional%20Plan%20to%20Local%20Control_revised.pdf

Unfried A, Faber M, Stanhope DS, Wiebe E (2015) The development and validation of a measure of student attitudes toward science, technology, engineering, and math (S-STEM). J Psychoeduc Assess 33(7):622–639. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282915571160

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2021, January 22) 2020 Annual Averages - Employed persons by detailed occupation, sex, race, and Hispanic or Latino ethnicity. Bls.gov. https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat11.htm

Vakil S (2014) A critical pedagogy approach for engaging urban youth in mobile app development in an after-school program. Equit Excell Educ 47(1):31–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2014.866869

Van Wormer K (2015) Oppression. International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 246–252

Whipp JL, Geronime L (2017) Experiences that predict early career teacher commitment to and retention in high-poverty urban schools. Urban Educ 52(7):799–828. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085915574531

Yeager DS, Romero C, Paunesku D, Hulleman CS, Schneider B, Hinojosa C, Lee HY, O’Brien J, Flint K, Roberts A, Trott J, Greene D, Walton GM, Dweck CS (2016) Using design thinking to improve psychological interventions: the case of the growth mindset during the transition to high school. J Educ Psychol 108(3):374–391. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000098

Zilberman A (2021, January 19) Why computer occupations are behind strong STEM employment growth in the 2019–29 decade: Beyond the Numbers: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Bls.gov. https://www.bls.gov/opub/btn/volume-10/why-computer-occupations-are-behind-strong-stem-employment-growth.htm

Acknowledgements

The Android Inventor study team gratefully acknowledges Jennifer Brady who graciously allowed us to conduct our research in her after-school program.

Funding

This study did not receive any funding or grants.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors were approved by the Homewood IRB HIRB00007654 as members of the study team. The corresponding author of this article, Dr. Sharon Mistretta, completed this study to fulfill the requirements of an applied dissertation in her Doctor of Education degree at Johns Hopkins University School of Education. Dr. Yolanda Abel served as Dr. Sharon Mistretta’s adviser to provide guidance in the foundations of the intersectionality theoretical framework, and the formation, implementation, and data analysis of the Android Inventor intervention documented in this article. Ms. Demi Matos served as a STEM Intern and Research Assistant during the formation, implementation, and data analysis of the Android Inventor intervention documented in this article. As Director of Education at the after-school program where this study took place, Ms. Jessica Egger developed the recruitment procedure of participants to this study, the schedule and structure of the Android Inventor program, and provided analysis of resulting data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There are no financial or non-financial conflicts of interest/competing interests regarding this study. The researchers do not have financial interest or benefit arising from the direct applications of our research.

Ethical approval

Johns Hopkins University School of Education, Homewood Campus Institutional Review Board provided the ethics approval to conduct this study Homewood IRB Number: HIRB00007654.

Consent to participate

All participants of this study were minors and received written consent to participate by their parents or guardians. All references to individuals in this study were anonymized to protect the identity of participants.

Consent for publication

This article is original, only submitted to this journal, and does not have any other competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mistretta, S., Abel, Y., Matos, D. et al. An after-school STEM program through the lens of intersectionality. SN Soc Sci 2, 52 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-022-00357-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-022-00357-0