Abstract

Objective

The COVID-19 pandemic uncovered innovative approaches in medical education. Modifications are needed to overcome the drawbacks of pure online teaching. Our study aimed at testing a hybrid method of live online practical anatomy sessions in which an element of face-to-face teacher-student interaction is maintained.

Methods

We performed an experiment with a one-group design in which medical and medical laboratory sciences students were taught different practical anatomy topics using either purely online or live in front of students teaching sessions (LISTS). Students’ performance and perceptions were quantitatively assessed.

Results

For 108 medical laboratory sciences students, the mean quiz scores were significantly higher for the topics taught by the LISTS approach (p = 0.025). For two groups of 13 and 17 medical students, the performance in exams was significantly higher for the topics taught using the LISTS method (p = 0.000 and 0.011, respectively) with large effect sizes. Students’ perceptions of preference, enjoyment, and satisfaction were all in favor of LISTS.

Conclusions

Our results confirmed that keeping at least a minimum of interaction between the teacher and students can have a significant improvement in the performance and engagement in practical anatomy sessions for health professionals. The results indicate that the extra effort of LISTS was worth it.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Currently, the world is fighting COVID-19 [1]. In March 2020, the WHO declared the COVID-19 outbreak a pandemic [2, 3]. The subsequent actions by colleges and universities forced the students to be moved away from the institutions [4]. Consequently, instruction was shifted from the traditional face-to-face method to online teaching [5].

The debate on the effectiveness of online education in medical schools is open for ongoing research [6]. Colleges and universities worldwide underwent a transition from traditional face-to-face teaching methods to online teaching or a combination of online and traditional teaching (blending) [7]. The blended method means replacing part of the traditional method with online teaching [8].

Of the challenges reported in the medical literature, there were many issues relating to the use of technology tools, time management, difficulty in students’ assessment and communication, and the lack of social interaction [9, 10], in addition to the inequity in access and teaching quality [11]. Some students face difficulties in having laptops, or the internet at home, in addition to the many difficulties faced by older individuals [12].

In contrast, many educators consider the pandemic as a true opportunity for implementing technology in medical education in an effective way for improvement [1], fastening the already-established transition to online education, considered an effective replacement for traditional education [7, 13].

There are many multi-campus medical schools around the world that routinely use approaches similar to the approach we used. The delivery of medical curriculum in multi-campus schools can be different due to factors related to the location [14]. Previous studies emphasized the usefulness of this hybrid approach and how it is dependent on different contextual factors [15, 16]. The COVID-19 lockdown shifted the education to be completely online in many countries. Herein, the approach we used became a valuable attempt to increase students’ interaction as much as possible, even with the small number of students permitted due to the safety precautions. In this situation, social distancing and limited students in face-to-face teaching differ from the routinely applied methods in multi-campus medical schools.

According to the behaviorism learning theory, students’ interaction with their environment and the positive reinforcements they receive significantly affect their behaviors and information retention [17]. In an attempt to make the learning environment more effective, the present study aims to test a mixed approach for teaching practical anatomy in which face-to-face teaching is done for 20% of each student group with social distancing, and at the same time, the session is livestreamed to the remaining students online.

Materials and Methods

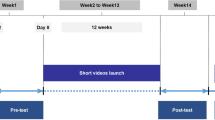

Medical students and medical laboratory sciences students at Al-Balqa Applied University (BAU) were invited to participate in a variety of additional practical anatomy sessions. A 108-group of medical laboratory sciences students were taught the topics nose/paranasal sinuses and mediastinum purely online (a recorded video by the instructor alone was streamed to the students). The topics pharynx, larynx, trachea/bronchi, and lungs were taught by the instructor while keeping face-to-face interaction with a small group of students (LISTS) (Fig. 1), and at the same time, the session was livestreamed to the remaining students. In this interactive environment, the teacher directly interacts with the face-to-face group and positively reinforces them to better learn the concept while all the activity is livestreamed online. Another group of 13 medical students was taught nose/paranasal sinuses and larynx online, while they were taught the pharynx by LISTS. On the other hand, a group of 17 medical students was taught the larynx and pharynx by LISTS, while they were taught the nose/paranasal sinuses purely online. Both methods were used by the same anatomy instructor who was experienced in both traditional and online teaching methods. An online test and a questionnaire were answered by the students. For the tests, multiple-choice questions were used, and the maximum score for each test was 12. The questionnaire was anonymous, predesigned, and self-administered. The questionnaire was marked according to a 5-point Likert scale where strongly agree/agree responses are lumped together as a positive response. Independent t tests were used and p value < 0.05 was considered significant. Cohen’s d was used to calculate the effect size. SPSS V19 was used for statistical analysis.

Results

Students’ perceptions of preference, enjoyment, and satisfaction were all in favor of LISTS. The students’ responses to all questionnaire elements were impressive. Of the 108 medical laboratory sciences students who answered the questionnaire, seventy-six students felt that LISTS is more useful than a purely online approach. Eighty-three students felt that LISTS is more fun, and 78 felt that it is more interesting. Interestingly, seventy-nine students found LISTS was much better in knowledge retention when compared with the pure online sessions. Moreover, seventy-four students mentioned that LISTS improves the skills in practical anatomy more. Seventy-two students preferred LISTS in general, and 79 felt it more satisfying. Seventy-seven students mentioned that LISTS encouraged them to be more involved in class discussions. Seventy students felt that LISTS can be easily applied. The questionnaire elements are shown in Table 1.

For 108 medical laboratory sciences students, the mean quiz scores were significantly higher for the topics taught by the LISTS (pharynx, larynx, trachea/bronchi, and lungs) vs online (nose/paranasal sinuses and mediastinum) approach (Table 2). For two groups of 13 (group A) and 17 (group B) medical students, the performance in exams was significantly higher for the topics taught using the LISTS vs online method (LISTS—pharynx vs online—nose/paranasal sinuses and larynx and LISTS—larynx/pharynx vs online—nose/paranasal sinuses, respectively) with large effect sizes (Cohen’s d 1.57 and 0.85, respectively).

Discussion

From its earliest days, teaching has attempted to create an active discussion with the students present in the classrooms. Most university educational activities grew out of the traditional classrooms. No one was quite sure if teaching and or learning could survive without student interaction.

In spite of the disadvantages of online education such as the limited modules that can be taught online, the loss of communication and interaction, and the technical problems that can be faced, there are many advantages as well. Online learning is a flexible method of learning where the study material can be learned anytime and anywhere [18].

LISTS is a medium meant for knowledge dissemination to student audiences, but it is also streamed directly online over the internet to students at home, a form of a combination of online lecturing and student audience. LISTS requires a fraction of the students to attend the lecture in the classroom and another big fraction to leave the classroom and sit down in front of a computer desk or a laptop to follow the lecture while perceiving the students’ interaction.

Several online methods have been used for teaching anatomy. However, face-to-face interaction in practical anatomy sessions is important [19]. In spite of the critical changes that occurred to many medical curricula and which affected the level of students’ knowledge of anatomy, the importance of anatomy in all aspects of clinical years cannot be ignored [20].

At Al-Balqa Applied University, we took this new idea and used Microsoft Teams™ to refine an approach to record and stream lectures in front of a live student audience using smart cameras, capturing the lecturer from different angles.

Using the LISTS format, we aimed to get the strengths of live lecturing (audience interaction, letting the professors feed off of the audience’s energy) and live online streaming. This technique is a hybrid of both face-to-face and online teaching, and it is hoped that this will become one of the truly original education at Al-Balqa Applied University.

While the world of education has swung back and forth during the COVID-19 pandemic between the direct face-to-face education and in-home online education for roughly 10 months, this new method of education will provide a small representative sample of student audience to maintain the sense of face-to-face education to make the learning environment more effective.

In the last 10 months or so, university education has begun what seems like an irrevocable process of shutting classrooms out of the picture of higher education. Sure, there is some laboratory education, for instance—that will probably always require students to come to universities. But in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic, the need for students to attend universities has become less and less important if not risky. In LISTS, a relatively small number of students may attend university classes every week, while the rest of the students attend the classes online.

Many multi-campus medical schools routinely use approaches similar to LISTS. However, the COVID-19 lockdown shifted education to be completely online in many countries. The approach we used is an attempt to increase students’ interaction as much as possible. However, in this model, the number of students is smaller, and social distancing is considered.

Conclusions

The students’ performance in exams was significantly better when LISTS was used in comparison to the pure online teaching method. Students’ preferences were significantly in favor of LISTS. LISTS represent an innovative, prompt, and flexible method for improving medical education in a situation such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

CDC: coronavirus (COVID-19). 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/index.html. Accessed 15 Apr 2020.

WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19. 2020. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-sopening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-.... Accessed 22 Mar 2020.

WHO: what is a pandemic?. 2010. https://www.who.int/csr/disease/swineflu/frequently_asked_questions/pandemic/en/. Accessed 11 Mar 2020.

‘Panic-gogy’: teaching online classes during the coronavirus pandemic. 2020. https://www.npr.org/2020/03/19/817885991/panic-gogy-teaching-onlineclasses-during-the-coronavirus-pandemic. Accessed 20 Mar 2020.

Will shift to remote teaching be boon or bane for online learning?. 2020. https://www.insidehighered.com/digital-learning/article/2020/03/18/mostteaching-going-remote-will-help-or-hurt-onlin. Accessed 19 Mar 2020.

Rajab MH, Gazal AM, Alkattan K. Challenges to online medical education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cureus. 2020;12.

Orlearns M. Cases on Critical And Qualitative Perspectives in Online Higher Education. DeMarco A, Wolfe K (ed): IGI Global, Hershey, PA. 2014.

Edginton A, Holbrook J. A blended learning approach to teaching basic pharmacokinetics and the significance of face-to-face interaction. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74:88. https://doi.org/10.5688/aj740588.

Esani M. Moving from face-to-face to online teaching. Clin Lab Sci. 2010;23:187–190. https://doi.org/10.29074/ascls.23.3.187.

Rajab MH, Gazal AM, Alkawi M, Kuhail K, Jabri F, Alshehri FA. Eligibility of medical students to serve as principal investigator: an evidence-based approach. Cureus. 2020;12: e7025. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.7025.

How does the pandemic affect U.S. college students? Temple University, Philadelphia. CNN interview. 2020. http://www.pbs.org/wnet/amanpour-andcompany/video/how-does-pandemic-affect-low-income-students-nufk5j/ Accessed 2 Apr 2020.

Nimrod G. Technophobia among older Internet users. Educ Gerontol. 2018;44:148–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601277.2018.1428145.

Hixon E, Buckenmeyer J, Barczyk C, Feldman L, Zamojski H. Beyond the early adopters of online instruction: motivating the reluctant majority. Internet High Educ. 2012;15:102–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2011.11.005.

Gallagher S, Gladman T, Macfarlane E, Hallman S, Hutton J, Paterson H. Student use of common online resources in a multi-campus medical school. MedEdPublish. 2021;10.

Ellaway RH, Pusic M, Yavner S, Kalet AL. Context matters: emergent variability in an effectiveness trial of online teaching modules. Med Educ. 2014;48:386–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12389.

Han H, Nelson E, Wetter N. Medical students’ online learning technology needs. Clin Teach. 2014;11:15–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/tct.12092.

Arab M, Ghavami B, Akbari Lakeh M, Yaghmaie M, Hosseini-Zijoud SM. Learning theory: narrative review. Int J Med Rev. 2015;2:291–5.

Mirkholikovna DK. Advantages and disadvantages of distance learning. Hayкa и oбpaзoвaниe ceгoдня. 2020;7.

Mustafa AG, Taha NR, Alshboul OA, Alsalem M, Malki ME. Using YouTube to learn anatomy: perspectives of Jordanian medical students. BioMed Res Int. 2020.

Arráez-Aybar L-A, Sánchez-Montesinos I, Mirapeix RM, Mompeo-Corredera B, Sañudo-Tejero JR. Relevance of human anatomy in daily clinical practice. Annals of Anatomy - Anatomischer Anzeiger. 2010;192:341–8.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study’s conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Nidal A Younes, Ali Al Khader, Hadeel Odeh, Khaled Funjan Al-Zou’bi, and Tariq N Al-Shatanawi. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Nidal A Younes and Ali Al Khader, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the ethics committee at the faculty of medicine, Al-Balqa Applied University, Al-Salt, Jordan.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Younes, N.A., Al Khader, A., Odeh, H. et al. Live in Front of Students Teaching Sessions (LISTS): a Novel Learning Experience from Jordan During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Med.Sci.Educ. 32, 457–461 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-022-01510-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-022-01510-3