Abstract

In chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukaemia (CP-CML), residual BCR-ABL1+ leukaemia stem cells are responsible for disease persistence despite TKI. Based on in vitro data, CHOICES (CHlorOquine and Imatinib Combination to Eliminate Stem cells) was an international, randomised phase II trial designed to study the safety and efficacy of imatinib (IM) and hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) compared with IM alone in CP-CML patients in major cytogenetic remission with residual disease detectable by qPCR. Sixty-two patients were randomly assigned to either arm. Treatment ‘successes’ was the primary end point, defined as ≥0.5 log reduction in 12-month qPCR level from trial entry. Selected secondary study end points were 24-month treatment ‘successes’, molecular response and progression at 12 and 24 months, comparison of IM levels, and achievement of blood HCQ levels >2000 ng/ml. At 12 months, there was no difference in ‘success’ rate (p = 0.58); MMR was achieved in 80% (IM) vs 92% (IM/HCQ) (p = 0.21). At 24 months, the ‘success’ rate was 20.8% higher with IM/HCQ (p = 0.059). No patients progressed. Seventeen serious adverse events, including four serious adverse reactions, were reported; diarrhoea occurred more frequently with combination. IM/HCQ is tolerable in CP-CML, with modest improvement in qPCR levels at 12 and 24 months, suggesting autophagy inhibition maybe of clinical value in CP-CML.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML) is a clonal myeloproliferative neoplasm that originates from a constitutively active tyrosine kinase, BCR-ABL, resulting from a reciprocal translocation between chromosomes 9 and 22 [1, 2]. Upregulation of BCR-ABL drives disordered myelopoiesis through aberrant metabolism and expression of downstream signalling pathways [3, 4]. Despite a targeted therapeutic approach, disease persistence is driven by a small residual BCR-ABL1 positive (+) stem cell population [5,6,7,8,9]. This can lead to disease progression to the more acute form, termed blast crisis, which carries a very poor prognosis [10]. Measures to enhance the elimination of residual disease are therefore required to further improve outcomes and increase the number of patients obtaining deep molecular remission (DMR; defined as ≥4-log reduction in BCR-ABL transcript levels) who can be considered for discontinuation of TKI treatment and long-lasting treatment-free remission (TFR) [11,12,13].

Autophagy, an evolutionarily conserved catabolic process [14], is induced following in vitro tyrosine kinase inhibition (TKI) of primitive CML cells [15]. While autophagy has been shown to suppress cancer initiation in mouse models, an increasing amount of evidence suggests it plays a critical pro-survival role following therapeutic stress [16]. Furthermore, pharmacological autophagy inhibition, using the non-specific autophagy inhibitor, chloroquine (CQ), enhances the effect of TKI on functionally defined CML stem cells compared with Imatinib (IM) or CQ alone [15].

Based on these findings, we designed the CHOICES (CHlorOquine and Imatinib Combination to Eliminate Stem cells) trial (NCT01227135); a randomised, open-label, phase II clinical trial comparing the combination of IM and hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) with standard-of-care IM in chronic-phase (CP)-CML patients in major cytogenetic response (MCyR) with residual disease detectable by qPCR after at least 1 year of IM treatment. This is the first clinical trial of autophagy inhibition in leukaemia and provides a proof-of-concept for further development and testing of more potent and/or specific autophagy inhibitors for use in future leukaemia trials [17].

Methods

Patients

Eligible patients were 18 years or older with CP-CML. Patients had been treated with, and tolerated, IM for more than 12 months, achieved at least MCyR and remained BCR-ABL+ by qPCR. A stable dose of IM for 6 months prior to study entry was a prerequisite. Eligible patients had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) of 0–2 and adequate end-organ and marrow function, with no uncontrolled significant illness. Informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and with approval from Greater Glasgow and Clyde NHS Trust Ethics Committee. The “Hospices Civils de Lyon” (Lyon, France) were the sponsors within France. Following enrolment, the Cancer Research UK Clinical Trials Unit, Glasgow, were contacted to verify eligibility and undertake randomisation. Exclusion criteria are listed in Table 1.

Study design and objectives

This was an international multicenter, two-arm parallel, open-label, randomised phase II trial with a safety run-in, designed to study the safety and efficacy of HCQ in combination with IM (NCT01227135). Patients were randomly assigned at a one-to-one allocation ratio to IM in combination with HCQ (IM/HCQ) or IM alone. Random assignment was stratified using a minimisation algorithm, incorporating the following factors:

Baseline PCR level (<3 logs below baseline, ≥3 logs below baseline)

Time on IM (12–<24 months, 24 to <36 months, ≥36 months)

Daily IM dose (<400 mg, 400 to <600 mg, 600–800 mg)

Site

All patients continued once daily dosing of IM throughout the 24-month study period. Patients on the IM/HCQ arm received a maximum of 12 four weekly cycles of combination treatment (48 weeks). Patients were followed-up for a further 12 cycles, taking each patient’s total study participation to a maximum of 96 weeks. Orally administered HCQ was started at 800 mg/day as 400 mg twice daily. In the case of missed doses, patients were advised to take the drug on the same day if within 6 h, or the dose was withheld until the next scheduled dose. For dose reduction, 600 mg/day was divided into 400 mg every morning and 200 mg every night and 400 mg/day into 200 mg twice daily. Recruitment was temporarily stopped for 6 weeks once six patients were randomly allocated to IM/HCQ to monitor for evidence of any dose limiting toxicity (DLT). DLT was defined as (i) any grade 3 or 4 non-haematological toxicity that was/possibly was attributed to the study drug, excluding grade 3 nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea controllable by concomitant therapy, or (ii) any grade 3 or 4 haematological toxicity that could not be corrected by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor.

Definitions of end points

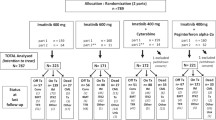

The primary study end point was the proportion of treatment ‘successes’, defined as patients who had ≥0.5 log reduction (approximately threefold reduction) in their 12-month BCR-ABL1 qPCR levels from trial entry. Patients who withdrew before the 12-month assessment or who had an increase in IM dose prior to the assessment were classified as treatment ‘failures’ in the primary end point analysis. To avoid bias in the primary end point, the assessment of qPCR levels was performed blind to the study treatment allocation. The secondary study end points were the proportion of treatment ‘successes’ at 24 months, molecular response at 12 and 24 months, comparison of IM levels (using metabolite CGP-74588) between study arms at 12 and 24 months (supplemental methods), and the proportion of patients who achieved therapeutic whole blood HCQ levels >2000 ng/ml at 12 and 24 months (supplemental methods). Patients who withdrew prior to 24 months were classified as treatment ‘failures’ in secondary end point analyses (Fig. 1).

BCR-ABL1 detection

Monitoring for BCR-ABL1:ABL1 was performed centrally at Imperial Molecular Pathology Laboratory, London, and all BCR-ABL1:ABL1 ratios were expressed according to the international scale (IS). Baseline BCR-ABL1:ABL1 was documented from local laboratory analysis (Table 2) and repeated centrally to enable subsequent longitudinal analysis of response. MMR was defined as 0.1%(IS) or lower, with 10,000 or more ABL1 control transcripts.

Statistical method

Using retrospective study data [18], ~30% of patients fulfilling the entry criteria were expected to obtain a ≥0.5 log decrease in BCR-ABL1 qPCR levels after 12 months of IM treatment (treatment ‘success’). To detect an increase in the proportion of treatment ‘successes’ from 30 to 50% required 33 patients per arm (80% power, 20% one-sided level of statistical significance). Randomisation was undertaken centrally using a computerised algorithm, which incorporated a random element to remove predictability and ensure groups were well-matched, using a minimisation approach (described above). At the end of the randomisation process, the patient’s treatment allocation and unique identifier were generated.

Analyses were performed using SPSS 22.0.0.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL) and were conducted on an intention-to-treat (ITT) basis. The comparisons between the study arms of “successes”/”failures”, progression, and molecular response rates used Fisher’s exact test. 95% confidence intervals for the difference in proportions were calculated using method 10 in RG Newcombe [19]. Molecular response rates, IM plasma levels and the most severe common terminology criteria of adverse events (CTCAE v4.0) grade observed per patient for individual adverse events over the 12-month study period and the 12-month follow-up period were compared between the study arms using the Mann–Whitney U test. Statistical analyses of in vitro data and continuous BCR-ABL1:ABL1 qPCR data were performed using the ‘NADA’ package in R (v3.3.3) to allow interpretation of values below the limit of detection [20, 21]. Adjustments for multiple testing were made, where appropriate, using the false discovery rate (FDR) approach [22], using the p.adjust function (‘fdr’ option) in R.

Results

Patient characteristics

From 22 April 2010 to 31 December 2014, 62 patients were randomly assigned to IM (n = 30) or IM/HCQ (n = 32). Demographic characteristics were similar between arms (Table 2). Pre-treatment peripheral blood (PB) qPCR was available for all patients enroled, with median BCR-ABL1:ABL1 ratio of 0.046% (inter-quartile range (IQR) 0.011–0.118%) in the IM arm, and 0.034% (IQR 0.012–0.047%) in the IM/HCQ arm. Duration of IM prior to study entry was similar. Additional chromosomal abnormalities within the Philadelphia + clone were identified at CML diagnosis in two patients in the IM arm (one with a variant Philadelphia chromosomal translocation and one with deletion of chromosome 12), and three in the IM/HCQ arm (trisomy 21, deletion of chromosome 9 and a double Philadelphia chromosome abnormality). One patient in the IM arm withdrew from the trial prior to trial initiation and received no treatment on study; six patients withdrew consent during the study (Fig. 1). Patients were followed-up for a minimum of 24 months.

Molecular efficacy

No statistical difference was demonstrated in ‘success’ rate between arms at 12 months (1.2% lower with IM/HCQ vs IM; 95% CI: 21.1% lower to 18.4% higher; one-sided p = 0.58; two-sided p = 0.99) (Table 3). Patients who withdrew before the 12-month assessment (n = 11) or who had an increase in IM dose prior to the assessment (n = 1) were classified as ‘failures’ (n = 5 with IM; n = 7 with IM/HCQ), which may account for this. At 12 months, MMR was achieved/maintained in 66.7% on IM versus 71.9% on IM/HCQ (5.2% higher in the IM/HCQ arm; 95% CI: 17.1% lower to 27.1% higher; one-sided p = 0.43; two-sided p = 0.78).

At 24 months, ‘success’ rate in the IM/HCQ arm was 20.8% higher than the IM arm (95% CI: 1.5% lower to 40.4% higher; one-sided p = 0.059; two-sided p = 0.090). Patients with a sample ~90 days prior to the expected 24-month time point, or at any time after, were eligible for analysis, with the closest sample to the scheduled 24-month date (before or after) chosen. The numbers classed as ‘failures’ due to failure to achieve the appropriate log reduction in BCR-ABL1:ABL1IS within the acceptable window of the 24-month expected assessment time was higher with IM (n = 19; 76%) compared with IM/HCQ (n = 13; 65.0%). At 24 months, DMR/MMR was achieved/maintained in 66.7% with IM, and 75.0% with IM/HCQ (8.3% higher in the IM/HCQ arm; 95% CI: 13.8% lower to 29.7% higher). There was a slight, but not significant, difference in rates of molecular response between the arms (one-sided p = 0.33; two-sided p = 0.58) at the one-sided 20% significance level. There was no significant difference between depth of molecular response at 12 or 24 months. No confirmed or suspected progressions at any time during the study were identified.

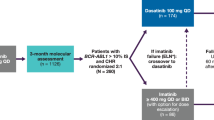

In view of the variation of BCR-ABL1:ABL1 ratio between patients (Table 2) at trial entry, a post hoc analysis was performed using the median BCR-ABL1:ABL1 ratio (0.0305%) to determine sub-groups of ‘high’ and ‘low’ BCR-ABL1:ABL1 expression at trial entry. MMR was not used as this led to a significant imbalance in subgroup sizes between the arms and would not have been informative. In the imatinib only arm, 24/30 patients were in MMR or better, and 6/30 not in MMR; in the IM/HCQ arm, 27/32 patients were in MMR, and 5 were not in MMR. At 12 months, within the high BCR-ABL1:ABL1 baseline group, the ‘success’ rate in the IM/HCQ arm was 4.7% higher than in the IM alone arm (95% CI: 26.5% lower to 32.2% higher; unadjusted two-sided p value > 0.99; FDR adjusted two-sided p value > 0.99), and within the low baseline BCR-ABL1:ABL1 group, the ‘success’ rate in the IM + HCQ arm was 10.5% lower than in the IM alone arm (95% CI: 34.6% lower to 16.4% higher; unadjusted two-sided p value = 0.61; FDR adjusted two-sided p value > 0.99). At 24 months, this difference is more striking, and the ‘success’ rate in the IM/HCQ arm is 34.6% higher than in the IM alone arm in those with high baseline BCR-ABL1:ABL1 (95% CI: 0.5% higher to 58.3% higher; unadjusted two-sided p value = 0.066; FDR adjusted two-sided p value = 0.26), and 3.8% higher in the low baseline BCR-ABL1:ABL1 subgroup (95% CI: 23.4% lower to 32.3% higher; unadjusted two-sided p value > 0.99; FDR adjusted two-sided p value > 0.99) (Fig. 2). This suggests that the kinetics of response is determined by BCR-ABL1:ABL1 ratio at trial entry and those with higher baseline levels may benefit more from the addition of HCQ to IM.

Separate trend lines are shown for each treatment arm, for patients with baseline BCR-ABL1:ABL1 greater than (“high” group) and less than or equal to (“low” group) the overall median value. Individual patient data (jittered) are overlaid. Values that are recorded as undetectable (zero) have been censored at 0.001%—the censored ranges are denoted by dotted lines.

Similarly, in a post hoc analysis utilising the median BCR-ABL1:ABL1 ratio at trial entry, we assessed the proportion of patients achieving a DMR, as defined by MR3, MR4, MR4.5 and MR5, at both 12 and 24 months. There was no significant difference in those achieving DMR between experimental arms of ‘high’ and ‘low’ BCR-ABL1 expressors. However, there was a higher trend for achievement of DMR within the IM/HCQ arm, particularly at 24 months (Table S1) where the proportion of patients in the ‘high’ BCR-ABL1:ABL1 subgroup achieving MR3 was 26.0% higher in the IM/HCQ arm (95% CI: 7.7% lower to 53.6% higher; unadjusted two-sided p value = 0.26; FDR adjusted two-sided p value = 0.85); MR4, 17.9% higher in the combination arm (95% CI: 13.9% lower to 43.4% higher; unadjusted two-sided p value = 0.41; FDR adjusted two-sided p value = 0.85); MR4.5, 16.7% higher in the combination arm (95% CI cannot be computed; unadjusted two-sided p value = 0.25; FDR adjusted two-sided p value = 0.85); and MR5, 11.1% higher in the combination arm (95% CI cannot be computed; unadjusted two-sided p value = 0.50; FDR adjusted two-sided p value = 0.85). Interpretation of this needs to be carefully considered as this will be underpowered by the very nature of a post hoc analysis.

Plasma levels

To ensure that HCQ did not interfere with IM plasma levels, and that patients were achieving an adequate dosage of HCQ, plasma levels of drugs in both study arms were determined. IM plasma levels were assessed in the ITT population, excluding the 12 patients (n = 6 in both arms) in the safety run-in period where blood samples were not taken, and those that withdrew consent. Plasma levels were taken 20–26 h after the last dose of drug in cycles 1, 2, 4, 7, 10 and 13. There was no significant difference, with an adjustment for multiple comparisons using the FDR approach, in trough IM levels between the arms at any time point. However, there was a trend towards increased CGP metabolite (IM metabolite) plasma levels relative to baseline at all time points in the IM/HCQ arm compared with IM alone. These differences reached statistical significance at the two-sided 10% level at cycle 2 (unadjusted two-sided p = 0.032; FDR adjusted two-sided p = 0.090) and cycle 13 (unadjusted two-sided p = 0.036; FDR adjusted two-sided p = 0.090) (Fig. S1A).

HCQ plasma levels were aiming to achieve a trough concentration of >2000 ng/ml at the time points described above. Only 47.1% (n = 8/17) achieved this trough HCQ plasma concentration at any time point during the 12 months of IM/HCQ treatment. There was no correlation between the likelihood of achieving treatment ‘success’ and achieving this trough HCQ concentration (Fig. S1B).

Autophagy inhibition was additionally determined ex vivo using the lipidated form of microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3B (LC3B-II) levels as a marker of autophagosomes. Bone marrow and PB samples were collected at baseline, 6 and 12 months (Table S2). In line with recent findings demonstrating increased autophagy flow in primitive CML cells [23], the number of LC3B-II puncta was significantly increased in BM-derived CD34+ samples, when compared with PB mononuclear cells (p = 0.002) (Fig. S2A). LC3B-II puncta were often undetectable in PB and, as expected, ex vivo HCQ treatment was required to determine LC3B-II expression (Fig. S2B). We demonstrated no linear correlation with trough IM/HCQ levels and degree of LC3B-II levels (data not shown). We did not demonstrate a reduction in colony-forming cell or long-term culture-initiating cell potentiation with IM/HCQ compared with IM alone (Fig. S2C, D).

Safety analysis

Recruitment was temporarily stopped for 6 weeks once six patients were randomly allocated to IM/HCQ to monitor for evidence of DLTs. No evidence of toxicity at a dose of HCQ 800 mg/day was determined.

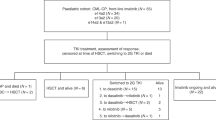

Toxicity was graded according to the CTCAE v4.0, and the worst grade determined for each patient in the first 12 months of treatment (Fig. 3A) and the 12 months follow-up (Fig. 3B). Treatment was generally well tolerated. During treatment, 4/29 treated patients developed hyponatraemia with IM (three at grade 3 [one present at grade 1 pre-treatment] and one grade 1), compared with 0/32 on IM/HCQ (p = 0.031). Diarrhoea was more common, with higher CTCAE grade, in the IM/HCQ arm with 21/32 patients affected (ten grade 1, eight grade 2 and three grade 3) compared with 7/29 patients on IM alone (six grade 1 and one grade 2; p = 0.00031). Grade 1 musculoskeletal problems were seen with IM (n = 8), but not with IM/HCQ (p = 0.0015). There were no cases of retinopathy documented within the IM/HCQ cohort.

The percentage of patients on each arm with toxicities and adverse events present at any grade and grade ≥2 are presented, restricted to toxicities and adverse events where at least 10% of patients on either arm experience worse grade ≥1 during the relevant period. The two-sided p value from a Mann–Whitney test comparing the distribution of grades between treatment arms is presented for each CTCAE-defined toxicity. Significant differences between arms at the two-sided 5% level are depicted (*).

During the trial period, 17 serious adverse events were reported; four were considered serious adverse reactions (SARs). Within the IM arm, dyspepsia was reported. Three SARs occurred in the IM/HCQ arm, and included one case each of cardiac rhythm disorder, dyspnoea and heart failure. Cardiac function fully recovered following discontinuation of HCQ in the patient with heart failure.

No dose reductions for IM were recorded for any patients during the study. Eleven patients (n = 4 on IM, and n = 7 on IM/HCQ) discontinued with ‘on trial’ IM treatment. The reasons included consent withdrawal (n = 6), rising BCR-ABL1:ABL1 ratio (n = 2), sub-optimal IM plasma levels (n = 1), patient choice (n = 1 on IM/HCQ) and other medical conditions (depression CTCAE grade 2, n = 1). Within the IM/HCQ arm, six patients had a total of eight HCQ dose reductions (four patients had one reduction, two patients had two reductions). Dose reductions were related to diarrhoea (n = 5), fatigue (n = 2) and patient choice (n = 1). Twenty-five patients completed the 12 cycles of HCQ. Seven patients stopped HCQ before the end of the scheduled 12 cycles, due to withdrawing consent (n = 4), treatment-related toxicity (depression and insomnia (both CTCAE grade 2), n = 2) and rising BCR-ABL1:ABL1 ratio (n = 1). Overall the IM/HCQ combination was safe and well tolerated and side effects were manageable.

Discussion

It has been estimated that 30% of patients on TKI therapy fail to achieve a MMR at 2 years [24]. Furthermore, the incidence of progression to blast crisis under TKI treatment ranges between 0.7 and 4.5% per annum [25,26,27]. One mechanism postulated to contribute to this lack of TKI response is the phenomenon of disease persistence, which suggests that despite a targeted therapeutic approach, BCR-ABL-independent mechanisms are being exploited to sustain the survival of CML LSCs [5, 28, 29]. Autophagy has emerged as a critical factor in resistance to a number of chemotherapeutic agents and is an attractive approach in targeting CP-CML LSCs [15, 16]. In CML, reports suggest that BCR-ABL is a negative regulator of autophagy, with autophagy being induced following in vitro TKI treatment, and in vitro pharmacological autophagy inhibition enhances the effect of TKI on functionally defined CML stem cells [15, 30]. Other studies have demonstrated that BCR-ABL promotes autophagosome formation and that autophagy is essential for BCR-ABL-dependent leukemogenesis [31, 32], suggesting that BCR-ABL may affect autophagy differently during malignant transformation and progression, as has been suggested in other malignancies [33]. Together, this suggests that combination treatment with TKI and autophagy inhibition may lead to higher rates of sustained molecular response and reduced rates of molecular and clinical progression.

This phase II clinical trial was designed to compare the combination of IM and HCQ, with standard-of-care IM in CP-CML patients in MCyR with residual disease detected by qPCR. IM was used as, internationally, it remains the most commonly administered first-line therapy in CP-CML, and at the time of trial opening in 2010 and during early recruitment, it was the only approved TKI for first-line therapy in the UK. To date, and to our knowledge, this has been the largest autophagy trial in any malignancy and the first in leukaemia.

The primary study end point was defined as patients who had ≥0.5 log reduction in their 12-month BCR-ABL1:ABL1 qPCR ratio from trial entry (‘successes’). This end point is not conventionally used as a criterion clinically to evaluate efficacy of treatment response in a CML population. However, it is well documented that in CML patients with an IM-induced complete cytogenetic response, a minimum of a half-log increase in BCR-ABL1:ABL1 ratio (including loss of MMR) is a significant risk factor for future loss of complete cytogenetic response [34]. It was, therefore, felt that a reduction of this magnitude would be clinically significant. There was no statistical difference in ‘success’ rates between IM and IM/HCQ arms at 12 months. However, there was an increasing trend towards MMR in the IM/HCQ arm, and the number of ‘successes’ was 20.8% higher with IM/HCQ at 24 months (one-sided p = 0.059 two-sided p = 0.090).

A major difficulty in the interpretation of combination treatment efficacy is the significant heterogeneity of BCR-ABL1:ABL1 ratio at trial entry in both experimental arms, despite the depth of response being taken into consideration during the randomisation process. This is particularly relevant in view of the kinetic response that exists during TKI therapy, with a steeper slope and ‘faster’ kinetics noted until MMR is achieved. At trial entry, 47.2% and 31.3% of patients were not in MMR in IM and IM/HCQ arms, respectively. As stated above, however, combination treatment demonstrated a higher proportion of treatment ‘successes’, which is therefore likely to represent clinical significance. To evaluate this further, in a post hoc analysis, we demonstrated that those patients with ‘high’ expression of BCR-ABL1 (defined as >0.0305%, as based on the median level at trial entry) in the combination treatment arm were more likely to achieve both treatment ‘success’ and DMR at 12 and 24 months, suggesting that further research into autophagy inhibition in combination with TKI is warranted in those patients not achieving optimal treatment milestones on TKI alone.

Our results demonstrate that there may be a clinical advantage for 48 weeks IM/HCQ treatment on prolonged follow-up, with greatest effect noted at 24 months. This is intriguing as patients at 24 months were no longer taking combination treatment, suggesting that the effect of autophagy inhibition was long-lasting. We could hypothesise that this is due to alterations in the quiescent phenotype of the CML LSC leading to greater TKI response with prolonged use. This is similar to other trials targeting CML-LSCs where deeper and significant BCR-ABL1 transcript response was seen on prolonged follow-up (5 years) [35]. However, we did not establish autophagy inhibition in in vitro assays at 12 or 24 months, and in future work in this field, perhaps extending ex vivo assays to later time points, as well as including alternative cellular mechanisms, such as senescence, could be considered to more clearly define the changes in the functional properties of CML stem cells as a result of prolonged treatment of patients with autophagy inhibitors and continuing subsequent therapies.

As this was a randomised phase II trial, albeit with relatively small sample size, small treatment improvements will not be detected, and therefore the increasing trend towards MMR could be clinically significant. Furthermore, as described above, differences in TKI kinetic response needs to be considered in future clinical trials in this field, as well as the challenges in recruitment and trial dropouts (or ‘failures’) which meant the power to drive a robust statistical response was not achieved. There are increasing barriers in recruitment to CP-CML studies. Firstly, this is generally a ‘well’ population, who tolerates TKI treatment, has few follow-up appointments, and is challenged with a low rate of progression. Clinical trials in CP-CML confer increased hospital attendance, with more procedures, including bone marrow aspirates that are psychologically unappealing. However, as demonstrated by the frequent molecular recurrence seen in patients attempting TFR [11, 12, 36, 37], there is an unmet clinical need to develop therapies capable of targeting the CML LSC which is believed to be the cause of molecular recurrence, and enable more patients to obtain DMR and successfully maintain TFR.

Importantly, the combination of IM/HCQ was well tolerated and no DLTs were observed, although increased numbers of patients developed grade 1–3 diarrhoea, consistent with previous clinical trials using HCQ [38,39,40,41]. Diarrhoea and fatigue were the main reasons for dose reduction of HCQ, both recognised adverse effects [39, 42]. Interestingly, compared with IM alone, no patients developed musculoskeletal AEs with IM/HCQ compared with 8/29 on IM, in keeping with its known clinical utility in rheumatological disorders [43]. To our surprise, 4/29 patients developed hyponatraemia with IM alone. Although not identified as a significant toxicity in the IRIS clinical trial (NCT00006343) [44], hyponatraemia is recognised as an uncommon adverse event (>1:1000 to <1:100) of imatinib therapy [45].

Measuring autophagy flux accurately in PB is difficult, and functional assessment is therefore problematic. Plasma levels of HCQ were taken to determine therapeutic dosing, with target trough levels >2000 ng/ml. However, very recently published in vitro data from our group indicates that even if this was accomplished, at this trough concentration (equivalent to 5.9 µM) complete autophagy inhibition may not be achieved [23]. These data were not available when the trial was conducted. Furthermore, consistent HCQ plasma concentrations were not achieved within our trial population and large interpatient variability in HCQ levels has been demonstrated in a recent clinical trial, in combination with everolimus, in renal cell cancer [38]. Together, this perhaps explains the lack of correlation with in vitro assessment; an issue that has been previously demonstrated within solid tumours [46,47,48]. A major drawback to HCQ dose optimisation and ultimate achievement of autophagy inhibition is the risk of adverse effects when using higher doses for longer durations, particularly retinopathy [39, 49]. Retinopathy is unlikely to occur with dosages less than 6.5 mg/kg/day within the first 10 years of therapy [40]; we demonstrated no cases of retinopathy.

To overcome both inconsistent autophagy inhibition and mitigation of side effects, more potent and specific autophagy inhibitors are required. These are beginning to be assessed in pre-clinical models [23, 50, 51]. CQ derivatives, such as Lys05, have been shown to be three- to ten-fold more potent and have good effect in CML models. Within murine models, however, higher doses, led to Paneth cell dysfunction and intestinal obstruction [23, 51]. As yet, these have not been translated to clinical trial.

We conclude that while HCQ (at 400–800 mg daily) in combination with IM is a safe and tolerable treatment option in CP-CML, the primary end point of this study was not met, in part due to difficulties in recruitment and retention within the trial and in part due to failure to achieve adequate HCQ plasma levels. Our study suggests that clinically achievable doses of HCQ are unlikely to achieve a sufficient trough plasma concentration to accomplish meaningful autophagy inhibition. However, with more potent and specific autophagy inhibitors on the horizon and in pre-clinical development, this may be worth pursuing in future clinical trials with the aim to eradicate the CP-CML LSC.

References

Rowley JD. Letter: a new consistent chromosomal abnormality in chronic myelogenous leukaemia identified by quinacrine fluorescence and Giemsa staining. Nature. 1973;243:290–3.

Groffen J, Stephenson JR, Heisterkamp N, de Klein A, Bartram CR, Grosveld G. Philadelphia chromosomal breakpoints are clustered within a limited region, bcr, on chromosome 22. Cell. 1984;36:93–99.

Danial NN, Rothman P. JAK-STAT signaling activated by Abl oncogenes. Oncogene. 2000 ;19:2523–31.

Kuntz EM, Baquero P, Michie AM, Dunn K, Tardito S, Holyoake TL, et al. Targeting mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation eradicates therapy-resistant chronic myeloid leukemia stem cells. Nat Med. 2017;23:1234–40.

Bhatia R, Holtz M, Niu N, Gray R, Snyder DS, Sawyers CL, et al. Persistence of malignant hematopoietic progenitors in chronic myelogenous leukemia patients in complete cytogenetic remission following imatinib mesylate treatment. Blood. 2003;101:4701–7.

Deininger M. Stem cell persistence in chronic myeloid leukemia. Leuk Suppl. 2012;1:S46–48.

Graham SM, Jorgensen HG, Allan E, Pearson C, Alcorn MJ, Richmond L, et al. Primitive, quiescent, Philadelphia-positive stem cells from patients with chronic myeloid leukemia are insensitive to STI571 in vitro. Blood. 2002;99:319–25.

Hamilton A, Helgason GV, Schemionek M, Zhang B, Myssina S, Allan EK, et al. Chronic myeloid leukemia stem cells are not dependent on Bcr-Abl kinase activity for their survival. Blood. 2012;119:1501–10.

Corbin AS, Agarwal A, Loriaux M, Cortes J, Deininger MW, Druker BJ. Human chronic myeloid leukemia stem cells are insensitive to imatinib despite inhibition of BCR-ABL activity. J Clin Investig. 2011;121:396–409.

Kinstrie R, Karamitros D, Goardon N, Morrison H, Hamblin M, Robinson L, et al. Heterogeneous leukemia stem cells in myeloid blast phase chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood Adv. 2016;1:160–9.

Mahon FX, Rea D, Guilhot J, Guilhot F, Huguet F, Nicolini F, et al. Discontinuation of imatinib in patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia who have maintained complete molecular remission for at least 2 years: the prospective, multicentre Stop Imatinib (STIM) trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:1029–35.

Saussele S, Richter J, Guilhot J, Gruber FX, Hjorth-Hansen H, Almeida A, et al. Discontinuation of tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy in chronic myeloid leukaemia (EURO-SKI): a prespecified interim analysis of a prospective, multicentre, non-randomised, trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:747–57.

Clark RE, Polydoros F, Apperley JF, Milojkovic D, Rothwell K, Pocock C, et al. De-escalation of tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy before complete treatment discontinuation in patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia (DESTINY): a non-randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2019;6:e375–83.

Dikic I, Elazar Z. Mechanism and medical implications of mammalian autophagy. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2018;19:349–64.

Bellodi C, Lidonnici MR, Hamilton A, Helgason GV, Soliera AR, Ronchetti M, et al. Targeting autophagy potentiates tyrosine kinase inhibitor-induced cell death in Philadelphia chromosome-positive cells, including primary CML stem cells. J Clin Investig. 2009;119:1109–23.

Amaravadi R, Kimmelman AC, White E. Recent insights into the function of autophagy in cancer. Genes Dev. 2016;30:1913–30.

Chude CI, Amaravadi RK. Targeting autophagy in cancer: update on clinical trials and novel inhibitors. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:E1279.

Marin D, Milojkovic D, Olavarria E, Khorashad JS, de Lavallade H, Reid AG, et al. European leukemiaNet criteria for failure or suboptimal response reliably identify patients with CML in early chronic phase treated with imatinib whose eventual outcome is poor. Blood. 2008;112:4437–44.

Newcombe RG. Interval estimation for the difference between independent proportions: comparison of eleven methods. Stat Med. 1998;17:873–90.

Lee L. NADA: Nondetects and Data Analysis for Environmental Data. 2017. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=NADA.

R Foundation for Statistical Computing. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2017. https://www.R-project.org/.

Benjamini Y, Hochberg M. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc B. 1995;57:289–300.

Baquero P, Dawson A, Mukhopadhyay A, Kuntz EM, Mitchell R, Olivares O, et al. Targeting quiescent leukemic stem cells using second generation autophagy inhibitors. Leukemia. 2019;33:981–94.

Kantarjian H, Cortes J. Considerations in the management of patients with Philadelphia chromosome-positive chronic myeloid leukemia receiving tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1512–6.

Cortes JE, Kim DW, Pinilla-Ibarz J, le Coutre P, Paquette R, Chuah C, et al. A phase 2 trial of ponatinib in Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemias. N. Engl J Med. 2013;369:1783–96.

Hehlmann R, Lauseker M, Jung-Munkwitz S, Leitner A, Muller MC, Pletsch N, et al. Tolerability-adapted imatinib 800 mg/d versus 400 mg/d versus 400 mg/d plus interferon-alpha in newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1634–42.

Hughes TP, Lipton JH, Spector N, Cervantes F, Pasquini R, Clementino NC, et al. Deep molecular responses achieved in patients with CML-CP who are switched to nilotinib after long-term imatinib. Blood. 2014;124:729–36.

Chomel JC, Bonnet ML, Sorel N, Sloma I, Bennaceur-Griscelli A, Rea D, et al. Leukemic stem cell persistence in chronic myeloid leukemia patients in deep molecular response induced by tyrosine kinase inhibitors and the impact of therapy discontinuation. Oncotarget. 2016;7:35293–301.

Holyoake TL, Vetrie D. The chronic myeloid leukemia stem cell: stemming the tide of persistence. Blood. 2017;129:1595–606.

Sheng Z, Ma L, Sun JE, Zhu LJ, Green MR. BCR-ABL suppresses autophagy through ATF5-mediated regulation of mTOR transcription. Blood. 2011;118:2840–8.

Colecchia D, Rossi M, Sasdelli F, Sanzone S, Strambi A, Chiariello M. MAPK15 mediates BCR-ABL1-induced autophagy and regulates oncogene-dependent cell proliferation and tumor formation. Autophagy. 2015;11:1790–802.

Altman BJ, Jacobs SR, Mason EF, Michalek RD, MacIntyre AN, Coloff JL, et al. Autophagy is essential to suppress cell stress and to allow BCR-Abl-mediated leukemogenesis. Oncogene. 2011;30:1855–67.

Galluzzi L, Pietrocola F, Bravo-San Pedro JM, Amaravadi RK, Baehrecke EH, Cecconi F, et al. Autophagy in malignant transformation and cancer progression. EMBO J. 2015;34:856–80.

Press RD, Galderisi C, Yang R, Rempfer C, Willis SG, Mauro MJ, et al. A half-log increase in BCR-ABL RNA predicts a higher risk of relapse in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia with an imatinib-induced complete cytogenetic response. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:6136–43.

Gallipoli P, Stobo J, Heaney N, Nicolini FE, Clark R, Wilson G, et al. Safety and efficacy of pulsed imatinib with or without G-CSF versus continuous imatinib in chronic phase chronic myeloid leukaemia patients at 5 years follow-up. Br J Haematol. 2013;163:674–6.

Clark RE, Polydoros F, Apperley JF, Milojkovic D, Pocock C, Smith G, et al. De-escalation of tyrosine kinase inhibitor dose in patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia with stable major molecular response (DESTINY): an interim analysis of a non-randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2017;4:e310–16.

Etienne G, Guilhot J, Rea D, Rigal-Huguet F, Nicolini F, Charbonnier A, et al. Long-term follow-up of the French stop imatinib (STIM1) study in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:298–305.

Haas NB, Appleman LJ, Stein M, Redlinger M, Wilks M, Xu X, et al. Autophagy inhibition to augment mTOR inhibition: a phase I/II trial of everolimus and hydroxychloroquine in patients with previously treated renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25:2080–87.

Rangwala R, Leone R, Chang YC, Fecher LA, Schuchter LM, Kramer A, et al. Phase I trial of hydroxychloroquine with dose-intense temozolomide in patients with advanced solid tumors and melanoma. Autophagy. 2014;10:1369–79.

Rangwala R, Chang YC, Hu J, Algazy KM, Evans TL, Fecher LA, et al. Combined MTOR and autophagy inhibition: phase I trial of hydroxychloroquine and temsirolimus in patients with advanced solid tumors and melanoma. Autophagy. 2014;10:1391–402.

Vogl DT, Stadtmauer EA, Tan KS, Heitjan DF, Davis LE, Pontiggia L, et al. Combined autophagy and proteasome inhibition: a phase 1 trial of hydroxychloroquine and bortezomib in patients with relapsed/refractory myeloma. Autophagy. 2014;10:1380–90.

Chi KH, Ko HL, Yang KL, Lee CY, Chi MS, Kao SJ. Addition of rapamycin and hydroxychloroquine to metronomic chemotherapy as a second line treatment results in high salvage rates for refractory metastatic solid tumors: a pilot safety and effectiveness analysis in a small patient cohort. Oncotarget. 2015;6:16735–45.

Schapink L, van den Ende CHM, Gevers L, van Ede AE, den Broeder AA. The effects of methotrexate and hydroxychloroquine combination therapy vs methotrexate monotherapy in early rheumatoid arthritis patients. Rheumatology. 2019;58:131–4.

O’Brien SG, Guilhot F, Larson RA, Gathmann I, Baccarani M, Cervantes F, et al. Imatinib compared with interferon and low-dose cytarabine for newly diagnosed chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia. N. Engl J Med. 2003;348:994–1004.

Glivec 400 mg film-coated tablets. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/5566/smpc.

Gewirtz DA. The challenge of developing autophagy inhibition as a therapeutic strategy. Cancer Res. 2016;76:5610–4.

Wolpin BM, Rubinson DA, Wang X, Chan JA, Cleary JM, Enzinger PC, et al. Phase II and pharmacodynamic study of autophagy inhibition using hydroxychloroquine in patients with metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Oncologist. 2014;19:637–8.

Boone BA, Zeh HJ 3rd, Bahary N. Autophagy inhibition in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2018;17:25–31.

White E. Deconvoluting the context-dependent role for autophagy in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:401–10.

Mitchell R, Hopcroft LEM, Baquero P, Allan EK, Hewit K, James D, et al. Targeting BCR-ABL-Independent TKI resistance in chronic myeloid leukemia by mTOR and autophagy inhibition. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110:467–78.

McAfee Q, Zhang Z, Samanta A, Levi SM, Ma XH, Piao S, et al. Autophagy inhibitor Lys05 has single-agent antitumor activity and reproduces the phenotype of a genetic autophagy deficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:8253–8.

Acknowledgements

This manuscript is dedicated to TLH (1963–2017) who was instrumental in its concept, development and delivery. The study was funded by the Medical Research Council, grant number G0900882. This study was supported by the Glasgow Experimental Cancer Medicine Centre, which is funded by Cancer Research UK and the Chief Scientist’s Office, Scotland. Cell sorting facilities were funded by the Kay Kendall Leukaemia Fund (KKL501) and the Howat Foundation. We thank the site coordinators of the study and the participants. We thank Drs David Irvine and Susan Rhodes (Beatson West of Scotland Cancer Centre, Glasgow) for consenting and processing patient samples, and Drs Bruno Calabretta (Philadelphia University) and Paolo Salomoni (DZNE, German Centre for Neurogenerative Diseases) for useful discussions. Processing of samples was performed by Dr Alan Hair and Dr Heather Jorgenson (Paul O’Gorman Leukaemia Research Centre, University of Glasgow). FACS was performed by Miss Jennifer Cassels (Paul O’Gorman Leukaemia Research Centre, University of Glasgow). We thank Kim Appleton and Chantevy Pou in the development and contribution to the HCQ PK studies (University of Glasgow). We also thank Alison Holcroft (University of Liverpool) for carrying out the plasma imatinib levels. FEN acknowledges the work, the constant administrative help and data capture for French patients of Mrs Madeleine Etienne, CRA, haematology department, Centre Hospitalier Lyon Sud, Pierre Bénite, France and of Ms Clémence Van Boxsom, CRA, Délégation à la recherche Clinique of the Hospices Civils de Lyon, Lyon. This manuscript is dedicated to TLH, who tragically passed away on 30th August 2017.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

ALL: honoraria (Kite a Gilead Company), speakers bureau (Kite a Gilead Company) and consulting or advisory role (Jazz Pharmaceuticals). JB: honoraria (Novartis, Pfizer) and speakers bureau (Novartis, Pfizer, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Alexion). GS: research funding (Novartis, Pfizer, Ariad). SK: honoraria (Novartis, BMS, Pfizer, Incyte, Roche, AOP Pharma, Janssen, Bayer) and consulting or advisory role (Pfizer, Incyte, Novartis, AOP Pharma, BMS, CTI, Roche, Bayer). SK: research funding (Novartis, BMS, Janssen). THB: consulting or advisory role (Novartis, Pfizer, Janssen, Merck, Takeda) and research funding (Novartis, Pfizer). PS: honoraria (BMS, Novartis, Alexion, MerckSerono, Pfizer, MSD, Roche, Gilead) and consulting or advisory role (BMS, Novartis, Merck Serono, Alexion, Pfizer). PG: honoraria (BMS). FT: consulting or advisory role (bionomics) and research funding (Roche, Lilly, AstraZeneca). REC: honoraria (Novartis, Pfizer, BMS), consulting or advisory role (Novartis, Pfizer, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Abbvie) and research funding (Novarits, BMS). DM: consultancy and honoraria (ARIAD, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Pfizer, Incyte) and speakers bureau (Incyte). FEN: consulting or advisory role (Incyte, Sun Pharma Ltd) and speakers bureau (Incyte, BMS, Novartis). TLH (sadly passed away): research funding (Novartis, BMS), advisory board member (Novartis, Incyte), and honoraria (BMS, Novartis, Incyte). MC: research funding (Novartis, BMS, Cyclacel, Incyte), advisory board member (BMS, Novartis, Incyte, Pfizer), and honoraria (Astellas, BMS, Novartis, Incyte, Pfizer, Takeda, Celgene). The other authors have no competing financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Horne, G.A., Stobo, J., Kelly, C. et al. A randomised phase II trial of hydroxychloroquine and imatinib versus imatinib alone for patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia in major cytogenetic response with residual disease. Leukemia 34, 1775–1786 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-019-0700-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-019-0700-9

This article is cited by

-

Analysis of autophagy in DLBCL reveals subtype-specific differences and the preferential targeting of ULK1 inhibition in GCB-DLBCL provides a rationale as a new therapeutic approach

Leukemia (2024)

-

Targeting PP2A-dependent autophagy enhances sensitivity to ruxolitinib in JAK2V617F myeloproliferative neoplasms

Blood Cancer Journal (2023)

-

Protein tyrosine kinase inhibitor resistance in malignant tumors: molecular mechanisms and future perspective

Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy (2022)

-

Pharmacologic targeting of the P-TEFb complex as a therapeutic strategy for chronic myeloid leukemia

Cell Communication and Signaling (2021)

-

Safety of hydroxychloroquine in COVID-19 and other diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 53 randomized trials

European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology (2021)