Book contents

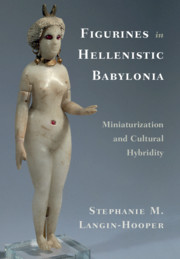

- Figurines in Hellenistic Babylonia

- Figurines in Hellenistic Babylonia

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Author’s Note

- Introduction

- Chapter One A Question of Intimacy: Miniaturization and Figurines

- Chapter Two Fascination with the Tiny: Interacting with Figurines

- Chapter Three Three’s a Crowd: Spectatorship of Figurines

- Chapter Four Images of the Self: Identifying with Figurines

- Chapter Five The Global and the Local: Making Cultural and Social Choices with Figurines

- Conclusion: Life in Miniature

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 19 December 2019

- Figurines in Hellenistic Babylonia

- Figurines in Hellenistic Babylonia

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Author’s Note

- Introduction

- Chapter One A Question of Intimacy: Miniaturization and Figurines

- Chapter Two Fascination with the Tiny: Interacting with Figurines

- Chapter Three Three’s a Crowd: Spectatorship of Figurines

- Chapter Four Images of the Self: Identifying with Figurines

- Chapter Five The Global and the Local: Making Cultural and Social Choices with Figurines

- Conclusion: Life in Miniature

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Figurines in Hellenistic BabyloniaMiniaturization and Cultural Hybridity, pp. 281 - 312Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2020