Book contents

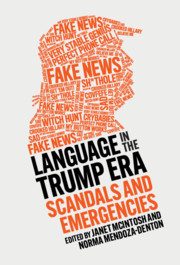

- Language in the Trump Era

- Language in the Trump Era

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- Note on Transcription Conventions

- Note on Ethnonyms and Phenotypic Descriptors

- Introduction: The Trump Era as a Linguistic Emergency

- Part I Dividing the American Public

- Part II Performance and Falsehood

- Part III The Interactive Making of the Trumpian World

- 9 Part III Introduction: Collusion: On Playing Along with the President

- 10 Banter, Male Bonding, and the Language of Donald Trump

- 11 On Social Routines and That Access Hollywood Bus

- 12 “Cocked and Loaded”: Trump and the Gendered Discourse of National Security

- 13 Evaluator in Chief

- 14 Fake Alignments

- Part IV Language, White Nationalism, and International Responses to Trump

- Index

- References

11 - On Social Routines and That Access Hollywood Bus

from Part III - The Interactive Making of the Trumpian World

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 18 September 2020

- Language in the Trump Era

- Language in the Trump Era

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- Note on Transcription Conventions

- Note on Ethnonyms and Phenotypic Descriptors

- Introduction: The Trump Era as a Linguistic Emergency

- Part I Dividing the American Public

- Part II Performance and Falsehood

- Part III The Interactive Making of the Trumpian World

- 9 Part III Introduction: Collusion: On Playing Along with the President

- 10 Banter, Male Bonding, and the Language of Donald Trump

- 11 On Social Routines and That Access Hollywood Bus

- 12 “Cocked and Loaded”: Trump and the Gendered Discourse of National Security

- 13 Evaluator in Chief

- 14 Fake Alignments

- Part IV Language, White Nationalism, and International Responses to Trump

- Index

- References

Summary

Trump’s “grab ’em by the pussy” remark was an example of a communicative “routine”: an interactional pre-fabricated exercise, seemingly innocuous, and often experienced as fun. In the type of routine Trump participated in, an Alpha individual establishes a superordinate position with respect to other participants (the In-group) by targeting an individual or group of individuals (Targets) outside the interaction, often by identifying the victim or victims with a social stigma. The stigma extends beyond the duration of the routine, and so has consequences for the Targets that extend well beyond the seemingly innocuous duration of the routine, often (but not always) violently threatening their physical well-being. The routine is familiar to the participants and – as social routines do – recruits the Alpha (Trump) and the In-group (his interlocutors) to their respective roles in an automatized way. There are significant negative consequences for not participating as an In-groupie, including exclusion from the group of interactants or even becoming the next target. Trump’s “grab ’em by the pussy” exchange was thus not just some individuals blowing off steam, but an example of a widely recognizable social routine that enlists interactants into its patterns and hierarchy.

Keywords

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Language in the Trump EraScandals and Emergencies, pp. 168 - 178Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2020