1. The Importance and Background of Iconography

When we face a work of art, a series of questions often arise. The initial question might be: "Who authored this work?" In the field of art history, this question is easy to answer. However, another equally important question quickly emerged: "What message does this work convey?" or more specifically: "What is its subject?" To explore and answer such questions, the field of art history formed a A specialized discipline, iconography.

Iconography aims to delve into the themes of works of art and the profound meanings contained within them. However, here, "theme" not only refers to the overall performance, but also includes the details in the work. Therefore, iconography covers the analysis from the whole to the details. For example, the difference in the number of trees in the picture may also become the object of iconographic research. "Profound meaning or connotation" refers to the deeper meaning that the work may contain. To sum up, iconography is dedicated to studying the themes of works of art and their profound connotations, providing us with a powerful tool for interpreting the meaning behind works of art.

Most people believe that the concept of iconology was first proposed by the German art historian Erwin Panofsky. In his book "Meaning in the Visual Arts" in the 1920s and 1930s, he systematically elaborated on the theory and methods of iconography for the first time. Panofsky's approach to iconography emphasized the interpretation of works of art from multiple levels, including symbolism, social history, and personal psychology, laying the foundation for subsequent art historical research and the development of iconography.[]

But as early as the 17th century Giovan Pietro Bellori (1613-1696) can be called the first person in iconography. Bellori was a famous artist, art historian and critic during the Italian Baroque period. Although the term iconography only became popular in more modern times, his book "Le vite de'pittori, scultori et architetti Moderni" and "Biography of the Artist" are of great significance to the development of iconography and art historical research have produced important inspirations.

This book records the lives and works of many artists at that time, and his analysis and comments on the artists' works are actually an early practice of iconography. His admiration for classical art and pursuit of ideal beauty reflects his concern for the deeper meaning and expression of artistic works. Although the term "iconography" was not directly used in his works, his interpretation and analysis methods of artistic works had an important impact on the development of the field of iconography. His views and methods helped subsequent researchers better understand the symbols, symbols and deep connotations of artistic works, which are important contents of iconography research. Therefore, it can be said that Bellori's works are closely related to the development of iconography.

Then, with the strengthening of international academic exchanges, the concept of "iconography" was first introduced to China in the 1980s, when Chinese academic circles began to focus on translating relevant works. In 1984, the Chinese translation of the word "Iconology" was determined to be "iconology", marking the official emergence of this concept in China. The concepts and methods of iconography began to attract attention and application in the field of Chinese art history research. With the expansion of cultural exchanges, iconography has gradually been introduced into the field of Chinese art history research.

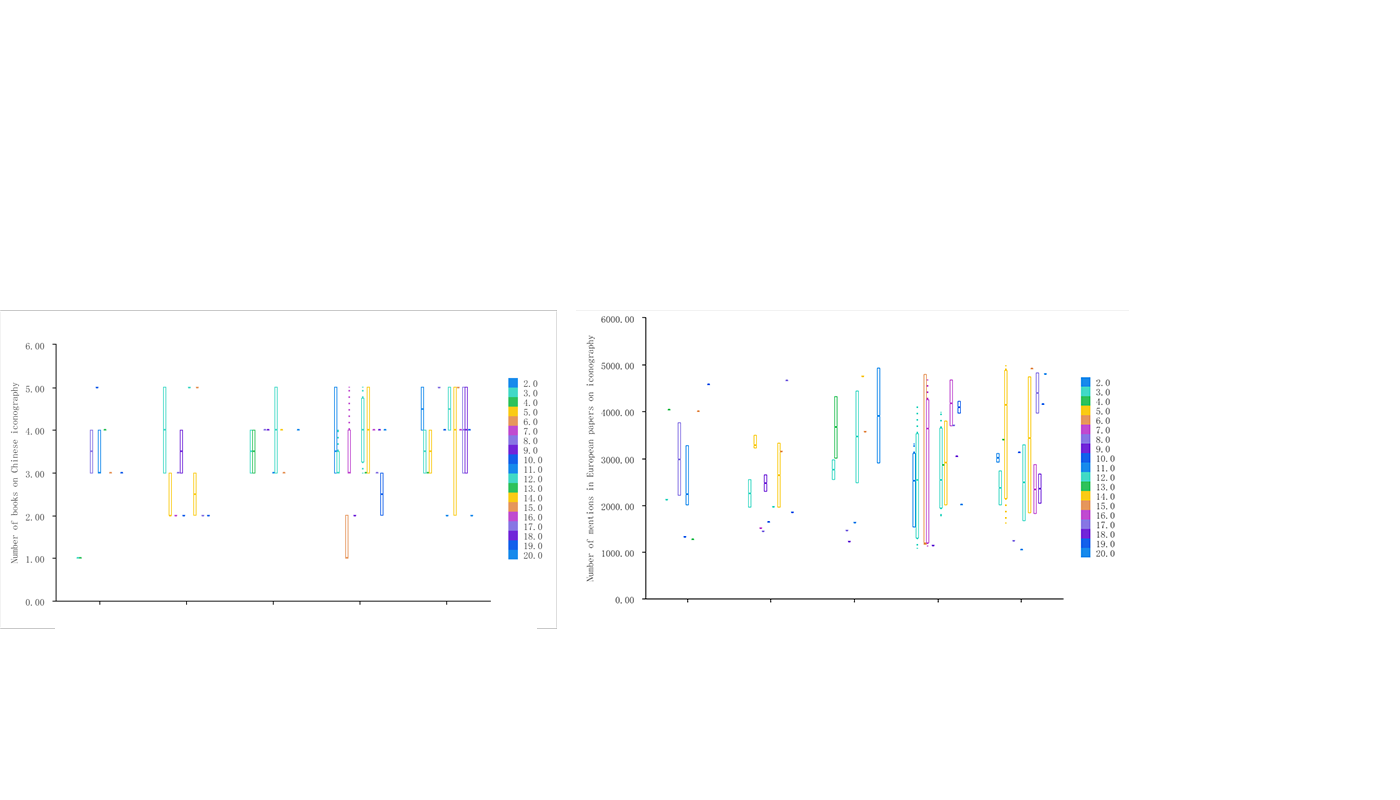

Figure 0: Tables of correlation analysis

As can be seen from the tables above, correlation analysis is used to study the correlation between Research on Chinese iconography, European iconographic studies and Number of mentions of Chinese iconography, Number of books on Chinese iconography, Number of mentions in European papers on iconography respectively, use the Pearson correlation coefficient to express the strength of the correlation relationship. Specific analysis shows:

The correlation coefficient value between Research on Chinese iconography and Number of mentions of Chinese iconography is 0.022, close to 0, and the p value is 0.829>0.05, which shows that there is no correlation between Research on Chinese iconography and Number of mentions of Chinese iconography relation. The correlation coefficient value between Research on Chinese iconography and Number of books on Chinese iconography is 0.224, and shows significance at the 0.05 level, which shows that there is a significant positive correlation between Research on Chinese iconography and Number of books on Chinese iconography. Related relationships.

From the data, we can clearly see that comparative research on Eastern and Western iconography is imperative and will play an important role in promoting the development of iconography and discipline construction in China.

With the introduction of the concept of iconography, China began to gradually establish a disciplinary system of iconography. Chinese scholars have begun to pay attention to the symbols, symbols and hidden cultural meanings in artistic works, and how to deeply interpret the works through image analysis methods. These studies include not only traditional paintings and sculptures, but also art in different media such as photography and film. However, due to different historical and cultural backgrounds, China is destined to establish its own iconography system based on its own conditions.

2. The Intertwining of Culture and Iconography

2.1. The Influence of Culture on Iconography

Culture is the core component of human society and affects people's thinking, values and artistic creation. In the field of art, iconography, as a methodology for interpreting works of art, is deeply influenced by culture. The same painting elements express and symbolize completely different contents in different cultural backgrounds. Cultural background shapes people's aesthetic concepts, symbol systems and artistic expression methods, which in turn affects iconologists' understanding of the theme, symbolic meaning and social background of the work.

As two regions with long histories and cultures, China and Europe each present unique characteristics and expressions. In Chinese culture, the values that emphasize harmony, balance and moderation are deeply valued. Nature is also regarded as an important element. Natural scenes and elements are often given symbolic meanings. The use of symbolism and metaphor is very common in artistic works, and in religion. In terms of culture, China is mainly influenced by Confucianism, Taoism and Buddhism. In European culture, the influence of Christianity and ancient Greek and Roman philosophy is more significant. Religion, philosophy, history and mythology have become the main artistic themes. Humanistic ideas focus on individual respect and expression, while modernism and expressionism pay more attention to emotion and expression. An expression of inner truth. These cultural characteristics directly affect the interpretation methods and emphasis of iconologists on artistic works. Understanding the differences between Chinese and European cultures can better reveal the deep connotation and significance of works, and enrich the application and research of iconography.

2.2. Characteristics and Manifestations of Chinese and European Cultures

As two important cultural traditions, China and Europe each have unique value systems, ways of thinking, and forms of artistic expression. These cultural characteristics directly affect iconologists’ interpretation methods and emphasis on artistic works. Comparing the cultural characteristics of China and Europe can deepen our understanding of the application and significance of iconography in different cultural backgrounds.

Characteristics and manifestations of Chinese culture: Chinese culture emphasizes the concepts of harmony, moderation and nature, and these ideas run through ancient Chinese art works. In Chinese painting, symbolism is often expressed in metaphors and symbols, conveying deeper thoughts through symbols and images. Ideological systems such as Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism have influenced the creations of Chinese artists, requiring iconologists to consider the influence of these cultural traditions when interpreting Chinese works.

Characteristics and manifestations of European culture: European culture is diverse and rich, from ancient Greek and Roman culture to Christian tradition, to stages such as the Renaissance and modernism, each period has left a unique artistic legacy. The interpretation of iconography in European art often involves reflections on religion, philosophy, history and politics. European artists' use of symbolism, allegory, and narrative requires iconologists to have a deep understanding of the European cultural background in order to better understand the meaning of the work.

For example, because of the implicit and moderate ideas in traditional Chinese thought, any nude works in ancient Chinese art works are absolutely unacceptable to the public. In European art works, nudity symbolizes beauty, purity, strength and perfection. Through the strong contrast between the characteristics and expressions of Chinese and European cultures, we can see the applicability and challenges of iconography in different cultural environments. Under the influence of intertwined cultures, iconography helps us more deeply understand and interpret artistic works in different contexts, revealing their profound connotations and cultural significance.

Table 1

Characteristics of Chinese Art | European art characteristics | Chinese Art Intensity (1-5) | European Art Intensity (1-5) | |

Cultural inheritance and philosophical thought | Influenced by Confucian, Taoist, and Buddhist philosophies; emphasis on harmony between nature and the universe | Influence of ancient Greek and Roman culture; prominent religious themes | 4 | 3 |

aesthetic concept | Simplicity, obscurity, philosophical emphasis | Form, perspective, attention to detail | 3 | 4 |

emotional expression | Introspection, silence, inner emotional expression | Dramatic, explicit, emotional direct presentation | 3 | 4 |

The impact of the era of globalization | Increased cultural integration and cross-cultural interactions | Creation and influence across cultural boundaries | 4 | 3 |

3. Symbolism and the Use of Symbols

Figure 1

"Travel to Streams and Mountains" is one of the works created by Fan Kuan, a famous painter in the Southern Song Dynasty of China. It was created around 1279 to 1280 AD and has a size of 206.3 cm × 103.3 cm. This painting uses ink as the main material, showing the classic characteristics of Chinese landscape painting. And there is a very typical symbolist romance that is unique to the Chinese.[]

Fan Kuan studied under Li Cheng (a Shandong painter of the Five Dynasties). He wrote in the "Xuanhe Painting Book" of the Northern Song Dynasty: "I first learned from Li Cheng, and after I realized it, I sighed and said: The method of the predecessors is not bad. It is not like learning from others. I am not as good as learning from others." If I were to learn from things, I would not be able to learn from the minds."

This passage illustrates the change in his thinking in his painting career. From the beginning, he fully studied the techniques and styles of his teacher, to the time when he believed that it is better to learn from the predecessors than directly from nature, so he lived in seclusion in Zhongnan Mountain, to the end, when he believed that learning from nature is not as good as learning from his own heart. The change in his ideas happened to be similar to the three changes in Western artistic thought from classicism to impressionism to post-impressionism.

Xu Beihong, a modern Chinese painter, once commented on this painting: "Of all the treasures in China, the Forbidden City has two treasures. The one I admire the most is Fan Zhongli's "Journey to Streams and Mountains". It is majestic, majestic and ancient, and is the work of thousands of people. This piece of "Woo Wu Wu" is a huge frame, and a mountain top occupies almost two-thirds of the total area. The composition is so abrupt that it makes people stunned. The entire painting is written without a single flaw. The skills of the people of the Northern Song Dynasty are really impressive."

As Mr. Xu Beihong said, the most exquisite thing about this painting is that it is more than 2 meters high, and the main mountain in the painting accounts for nearly two-thirds of the painting. It looks like a giant monument standing in front of people, so this work can also be called a "monument-like landscape". The entire picture is divided into three parts: foreground, middle ground, and backstage, which also correspond to the three realms of life.

The bottom part of the first part of the picture is full of rugged rocks, which visually blocks the road behind; the second part depicts gentle slopes, trees and streams, with the streams flowing slowly, a mountain path running across the center, and a caravan of donkeys. We are walking forward carrying goods; the third part is the mountain that occupies most of the picture. It blocks the sky and the sun, like an extremely sharp axe, suddenly splitting the clouds and fog and then standing steadily in front of us.

From the perspective of perspective, this painting is illogical. The first part of the strange rocks is a downward perspective, the second part is a horizontal perspective, and the third part is a upward perspective. Scientific perspective includes the perspective of a specific location and the scene seen from this fixed location. This is in line with the logical thinking of Westerners, but it is far from enough for Chinese painters. They ask questions like: "Why do we limit ourselves so much? If we already have a way to describe everything we know, why should we limit ourselves to describing a scene from just one perspective?" This attempt to express the three-dimensional world in a two-dimensional world coincides with Picasso's Cubism in Europe more than a thousand years later.

The three realms correspond to the three parts of the picture. The first level: be an ant who only looks at what is in front of you. On the road at the foot of the mountain, we saw two shirtless men fanning themselves and four donkeys carrying heavy loads. The heads of these donkeys were lowered, so it could be seen that the loads they carried were heavy and their steps were heavy. There were two people walking one behind the other, as if they only had donkeys in their eyes and did not care about the mountains next to them or the magnificent scenery around them. In their eyes, there was only life in this world and they only cared about the road in front of them. The road in front of them seems broad, but they can never look up and break through their own dimensions.

The second level: a cultivator who persistently seeks the Tao. In the middle ground of the picture, there is a vague figure in the trees on the left. It seems to be a person wearing a monk's robe, and this person is trying to find a way through the dense bushes and climb over the mountains and ridges to the picture. In the temple on the right side of the scene. From the picture, it seems that there is no way to go here. It can be imagined that this must be a difficult road. When we break away from the shackles of matter and come to the spiritual world, everyone is just a practitioner, but which path should I choose to reach the other side of my spiritual world? In order to understand this problem, we explore hard, just like the monk in the painting who persistently seeks the truth.

The third level: connecting with the sky and feeling the highest will of the universe. What will it feel like when we come to the third part of the picture, the majestic peak that fills the picture? We seem to be able to touch the sky with our hands, and even the clouds are below us. The waterfall in the mountains flows down three thousand feet and merges into the mountains and rivers in the distance. This mountain is extremely solid, and dense woods cover the top of the mountain, making it impossible for us to see its true clear appearance. Imagine that when we become one with this mountain, we seem to be able to touch the sky upwards, and downwards to gaze at the life below eternally and steadily, just like the Creator. At this moment, human joys and sorrows no longer matter. This is the spirit that Chinese paintings try to convey, which represents the highest will of the universe - everything in the world will not change in any way because of anyone or anything.

The other great interpreter of the romantic landscape, the German painter Caspar David Friedrich, was born in 1774 in Greifswald, on the North Sea; he has a melancholy childhood, marred by the death of his sisters, his mother and a brother who drowns in freezing water because of him.

Friedrich must be counted among the greatest landscape painters of all time. Solitary and introverted, he dedicates himself to the discovery of nature with the spirit of a monk or a poet of ancient China. Even if it is difficult to imagine direct knowledge, the Chinese landscapes of the 12th and 13th centuries appear very close to those of Friedrich in their spatial setting, with the elimination of intermediate planes, and in their quality as "landscapes of the soul". The underlying intent is quite similar: to make the landscape a mystical experience. For Friedrich and to an even greater extent for Chinese landscape painters, it is not just the representation of what you see (trees, mountains, fog, etc.) that is important; the possibility of communicating what you cannot see is much more important: the air that circulates between things, the void, the distance.

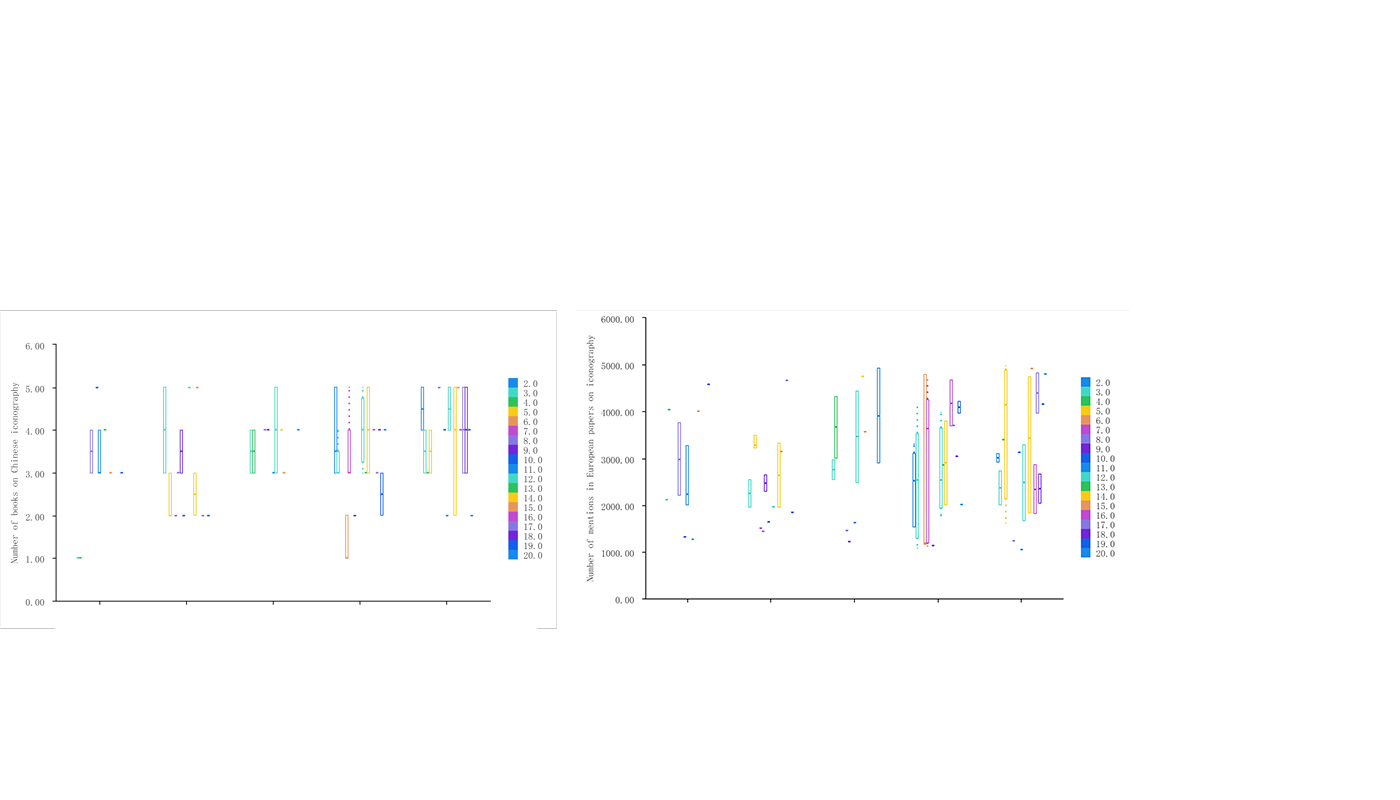

Figure 2

His wife remembers that when F. painted the sky in his paintings "it was impossible even to speak to him". Already in the early 19th century he began to be noticed for his substantial diversity and originality compared to his contemporaries: in the Cross in the Mountains, for the first time in the history of painting, he painted a landscape for an altarpiece. In the Abbey in the Oakwood, he overturns all the traditional canons of landscape composition.

The composition of the painting " The Abbey in the Oakwood" is similar to Fan Kuan's "Travel to Streams and Mountains". The painting is divided into three parts. The foreground part is the gray land and the monk standing on the ground thinking about the sea; The second part is the pitch-black sea, which looks extremely deep, and the white part above seems to be filled with scattered waves and seagulls; the third part is the sky full of dark clouds and mist that occupies three-quarters of the entire picture. The entire painting is composed of a series of horizontal lines, contrasting with the verticality of the monk's slender figure. The monk looks almost completely alienated from the world around him, as if he is oppressed by the boundless sea: he is offset from the visual center of the entire painting and has an unclear outline, not least because of its very small size compared to the entire painting. Small, but also because its color almost blends into the color of the dark sea. Although his back is turned to the observer, we can clearly feel the thousands of thoughts and endless emotions flowing from the depths of his soul. In fact, what we read is pain, melancholy, restlessness and confusion, as well as a profound inner loneliness.

For example, Kleist wrote:How wonderful it is to sit completely alone by the sea under an overcast sky, gazing out over the endless expanse of water. It is essential that one has come there just for this reason, and that one has to return.[] That one would like to go over the sea but cannot; that one misses any sign of life, and yet one senses the voice of life in the rush of the water, in the blowing of the wind, in the drifting of the clouds, in the lonely cry of the birds ... No situation in the world could be more sad and eerie than this—as the only spark of life in the wide realm of death, a lonely center in a lonely circle... Nevertheless, this definitively marks a totally new departure in Friedrich's art.

The great mastery with which Friedrich dedicated himself to the rendering of his landscapes is only a starting point for an operation of a spiritual nature: "The painter must not only paint what is in front of him, but also what he sees within himself. However, if you don't see anything in yourself, don't even paint what you see in front of you". This assumption, so clearly and simply expressed, applies to all his paintings, which we can try to explain starting from the romantic principle of "duality unified" (Novalis). On the one hand there is a methodical and rigorous, almost artisanal working technique, on the other a great depth and freedom of content, always combined with a symbolic background. The union of these two components, apparently so distant, keeps Friedrich away from a certain "rhetoric" of romanticism, based on easily grasped visual effects, and makes him a rigorous and particularly magical artist. For all of Friedrich's paintings, the knowledge of another Novalisian assumption can be valid, which takes us into the depths of the romantic experience of reality: "Giving the common a high meaning, the everyday a mysterious aspect, the semblance of the infinite to the finite ".

4. Multiple Levels of Interpretation of Metaphors and Symbols in Images

When discussing metaphors in works, one cannot avoid the religious-themed paintings of the European Renaissance. Any object in the paintings of that period may have some deep and special meaning. This has to mention Jeroen Bosch.

Jeroen Bosch was a prolific Dutch painter of the 15th and 16th centuries. Most of his paintings depict sinful indulgence and human morality. His paintings are very imaginative and creative, using a large number of symbols, and this painting "Death and the Miser" is a special expression of religious painting.

"Death and the Miser" is the most distant group in the triptych. The picture is divided into three layers from top to bottom. The insatiable protagonist occupies the main position in the center of the picture and appears twice. The first layer depicts armor and weapons abandoned on the ground, implying that the protagonist was once a brave knight. The most conspicuous position in the middle of the second floor is a treasure chest, which represents the sins most criticized by the medieval church, namely greed, materialism and gluttony.

We can see the sick protagonist still throwing money into the treasure chest. Inside and behind the treasure chests hide evil and rotten creatures from hell. Although the protagonist wears Catholic beads on his hands, these religious rules cannot save and change him. This is obviously a satire.

Figure 3

There is a pile of silk abandoned by the protagonist on the threshold. There is a little devil on the silk, facing left. Looks thin and weak. Some people say that this is a self-portrait that Bosch used to ridicule himself, expressing his love and helplessness. The third level of "Death and the Miser" is also the main position of the picture. The protagonist is dying on the bed. Death is waving to him at the door. An annoying little devil is holding a bag of gold coins to lure his soul. However, the protagonist cannot resist the temptation of the world and reaches out to get the gold bag provided by the devil. There is a demon on top of the bed looking down at the protagonist. We also see the protagonist's guardian angel praying behind him in anticipation of him looking up at the glory radiating from the cross. But the honor didn't seem to attract his attention. Although we don't know the protagonist's final choice, judging from the picture, the ending does not seem optimistic. Apparently, Bosch depicted the training in Mark 8:36: "What does it profit whoever gains the world but loses his own soul?" It would be truer to convey it in painting.

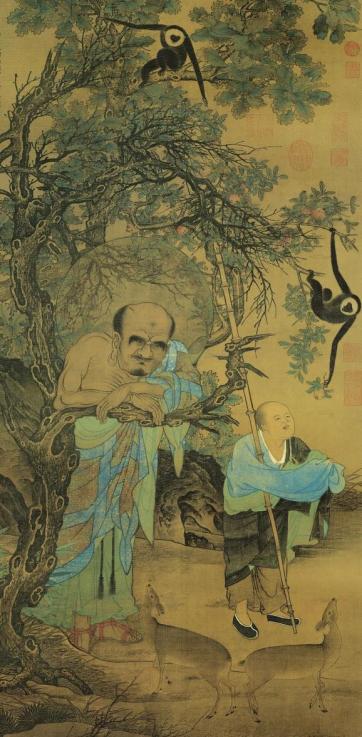

"Ape Offering Fruit", which is also a religious painting, is also a work that must be discussed in the field of Chinese painting iconography. This painting is one of the masterpieces of Liu Songnian, a famous Chinese painter from the Ming Dynasty, and was created in the 16th century AD. This painting uses delicate painting techniques and conveys profound cultural implications. It has always been loved and studied by art appreciators.

This painting uses ape images and Arhat (Sanskrit monks) as its main themes. The exotic identity of Arhat can be clearly seen through the facial image of Arhat in the painting. He is leaning on a branch, looking very leisurely. Next to him is a child holding a bamboo pole. A black ape is hanging on the branch offering pomegranates. The child is stretching out his hand. Pick up the pomegranate. The Arhat is sitting next to the tree, wearing a halo of holy light on his head, meditating on himself. Furthermore, the work demonstrates a high degree of artistic skill. The Arhat's face and cassock pattern are meticulously presented with superb painting techniques, giving the work more visual depth. The audience can clearly appreciate every detail, further enriching the entire picture.

"Ape Offering Fruit" is a masterpiece rich in symbolic themes, highlighting the profound influence of traditional Chinese culture.The ape image in the work carries the symbol of longevity and longevity, implying longevity and happiness. This symbolic concept has a deep history in Chinese culture and is often used to express people's wishes for health and prosperity.

The deer in the front of the picture is a type of deer, which is a homophone of "Lu" in Chinese, which means fortune. It is also a representative of auspiciousness and happiness.

Figure 4

The ape image forms an interesting contrast with the deer in the painting, which is a symbolic idea, because the ape represents vitality and restlessness, while the deer symbolizes wealth and tranquility.[] This contrast reflects the concept of balance and harmony in Chinese culture, implying balance and harmony in life. The animal images in the painting such as deer add to the vividness of the picture. The symbolic meaning of these animals is consistent with the meaning of Chinese cultural traditions, providing a fascinating layer for iconographic analysis.

In terms of layout and composition, the painter constructed a fascinating picture through the contrast between Arhat and ape. The Arhat's meditation and tranquility contrast sharply with the ape's activity, capturing the viewer's attention and further enhancing the appeal of the work.

Finally, the symbolism of the pomegranate also adds to the composition. It is regarded as a symbol of many children and good fortune. Since the heirs of the Southern Song Dynasty were dying at that time, this painting also implies the good wishes for the prosperity of the descendants of the dynasty. This symbol deepens the cultural connotation of the work and emphasizes the themes of longevity and auspiciousness. To sum up, "Ape Offering Fruit" conveys the theme of vitality, harmony and happiness of life through multiple symbols and meanings, and its unique artistic expression, giving the audience a profound artistic experience.

5. Enlightenment and Challenges of Cross-Cultural Iconology

The implications and challenges of cross-cultural iconography can be interestingly compared and observed in the above discussion of Chinese and Western works.

Although these painters come from different cultural backgrounds, they all pursue to express the mysterious beauty of nature and a cosmic view that is integrated with nature. This shows that images can transcend cultural differences and convey common emotional and spiritual experiences.

Whether it is Chinese landscape paintings and religious paintings or European romantic landscape paintings and religious paintings, they all reflect the awe and respect for nature, the beautiful expectations for the future, and the interpretation of human nature. This sensitivity to the natural world is a common thread in cross-cultural iconography, emphasizing the infinite allure of nature. The symbols and meanings in religious works may be affected by different cultural backgrounds. Iconologists need to fully understand these differences in order to accurately interpret and interpret these works.

Although Chinese landscape painting and European Romantic painting have similarities in expressing emotions, their perspectives, symbols and symbolism may be completely different. Cross-cultural iconography needs to overcome these cultural and contextual differences to ensure accurate interpretation and communication.

Chinese landscape painting and European Romantic landscape painting adopted different iconographic methods and compositional styles. This diversity is a challenge, but also an opportunity, as it encourages iconologists to explore different artistic traditions and enrich their research. The artistic styles and techniques in religious paintings are very different. This challenges researcher of cross-cultural iconography, as they need to understand different artistic traditions and methods of expression. It also reminds us that cross-cultural iconography requires broader interdisciplinary knowledge. []

Taken together, cross-cultural iconography reveals the similarities and differences between works of art in different cultural backgrounds, providing us with profound revelations and also posing research challenges that require an in-depth understanding of the contexts of different cultures. and artistic traditions. This kind of cross-cultural research helps expand our understanding of global artistic diversity and promotes cultural exchanges and cooperation.

References

[1]. Hasenmueller, Christine. “Panofsky, Iconography, and Semiotics.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, vol. 36, no. 3, 1978, pp. 289–301.

[2]. Hang Di. "Research on W.J.T. Mitchell's Image Theory and Visual Culture Theory" [D]. Shandong University, 2012.

[3]. Joseph Leo Koerner.Caspar David Friedrich and the Subject of Landscape, 2nd edition (London: Reaktion Books, Ltd., 2009/1990).

[4]. Dong Shuai. New interpretation of Liu Songnian's "Ape Offering Fruit" [J]. Chinese Art, 2021, (06): 89-96.

[5]. Childs, William A. P. “Iconography.” Greek Art and Aesthetics in the Fourth Century B.C., Princeton University Press, 2018, pp. 229–62.

Cite this article

Liu,Z. (2023). Iconography from A Cross-cultural Perspective: Comparison of Expressions in Chinese and European Art. Advances in Humanities Research,4,1-11.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer/Publisher's Note

The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s). EWA Publishing and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

About volume

Journal:Advances in Humanities Research

© 2024 by the author(s). Licensee EWA Publishing, Oxford, UK. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license. Authors who

publish this series agree to the following terms:

1. Authors retain copyright and grant the series right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this

series.

2. Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the series's published

version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial

publication in this series.

3. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and

during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See

Open access policy for details).

References

[1]. Hasenmueller, Christine. “Panofsky, Iconography, and Semiotics.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, vol. 36, no. 3, 1978, pp. 289–301.

[2]. Hang Di. "Research on W.J.T. Mitchell's Image Theory and Visual Culture Theory" [D]. Shandong University, 2012.

[3]. Joseph Leo Koerner.Caspar David Friedrich and the Subject of Landscape, 2nd edition (London: Reaktion Books, Ltd., 2009/1990).

[4]. Dong Shuai. New interpretation of Liu Songnian's "Ape Offering Fruit" [J]. Chinese Art, 2021, (06): 89-96.

[5]. Childs, William A. P. “Iconography.” Greek Art and Aesthetics in the Fourth Century B.C., Princeton University Press, 2018, pp. 229–62.