Re-Visiting the Role of Education on Poverty Through the Channel of Financial Inclusion: Evidence From Lower-Income and Lower-Middle-Income Countries

- 1Institute of Geography and Tourism, Baoding University, Baoding, China

- 2School of Business and Economics, United International University, Dhaka, Bangladesh

For attaining sustainable economic development in the lower and lower-middle-income nations, the role of poverty reduction has been critically addressed along with the economic determents that manage poverty level which has accelerated the economic progress by ensuring the higher performance of other macrovariables including FDI inflows, financial development, trade openness, and human capital accumulation. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the role of education and financial inclusion in poverty reduction in lower and lower-middle-income countries for the period 1995–2018, with a panel of 68 nations. The study applied several econometrical tools, including a cross-sectional dependency test (CDS), panel unit root test, panel cointegration test, generalized methods of moment (GMM), and system-GMM. The CDS results confirmed the sharing of typical dynamics in research units. The test of stationarity detected variables was integrated after the first difference. A panel cointegration test documented the long-run association between education, financial inclusion, and poverty. The study documented that government investment in education positively assists poverty reduction, implying a negative association between them. Furthermore, the inclusion of the population into the formal financial system expedited the poverty reduction process that has access to formal financial benefits allowing earning opportunities and higher purchasing power, eventually supporting an increased standard of living. Directional causality tests revealed feedback hypothesis holds in explaining the nexus between education, financial inclusion, and poverty, i.e., [ED←→Poverty; FI←→Poverty]. For policy reform and restructuring, it is essential to pay considerable attention to development in education and access to the formal financial system because progress in education and finance has positive spillover effects on the aggregated economy.

1 Introduction

Educational and physical endowments are crucial and significant components of human capital that enable people to be productive and increase their level of life. Human capital is necessary to efficiently use physical and natural resources, technology, and skills. The poverty reduction strategy document, which is one of the fundamental foundations of sustainable economic progress, has been held by developing countries (Singh and Chudasama, 2020). The objective of development or poverty eradication is impossible to achieve without human capital formulation, and human capital accumulation is heavily dependent on education and skill acquisition. In general, poverty refers to a situation in which a person or family cannot achieve the bare minimum requirements for survival in a particular community (Casserly, 2021). Appropriate food, potable water, suitable housing, health, education, transportation, and job are just a few of these fundamental necessities (Loayza and Raddatz, 2010). In developing nations, most of these necessities are decided by the market. Thus, the individual’s or household’s income or disposal resources always decide access to them. A family that does not earn enough money to meet the bare minimum of these fundamental demands in a particular society is consequently considered poor. Literature is abundant on economic and noneconomic ideas of poverty (Daw et al., 2011).

The progress of developing nations has surrounded several micro- and macro-phenomena with this note. Over the past decades, many issues have been discussed in various international gatherings, and poverty has emerged as the most detrimental factor for economic sluggishness. Macro-fundamental investigations, policy formulations, donor agencies’ contributions, and regional cooperation have been presented to achieve the unified goal of poverty reduction, especially in lower and lower-middle-income countries. Acknowledging the socioeconomic effects of poverty, many empirical studies have been performed by researchers to unleash the critical macro determinants that have played a decisive role in reducing poverty. As a result, several vital variables have established that those are critical in true means, such as investment in education (Tilak, 2002; Krueger and Malečková, 2003; Van der Berg, 2008; Augsburg, 2012; Serneels and Dercon, 2020), FDI (Magombeyi and Odhiambo, 2017; Magombeyi and Odhiambo, 2018; Ahmad et al., 2019), financial development (Jalilian and Kirkpatrick, 2002; Jalilian and Kirkpatrick, 2005; Azam et al., 2016; Ho and Iyke, 2017; Zahonogo, 2017; Saidu and Marafa, 2020), remittance (Ekanayake and Moslares, 2020; Musakwa and Odhiambo, 2020), financial inclusion, and microcredit expansion (Donou-Adonsou and Sylwester, 2016), among others.

Poverty is frequently linked to poor educational achievement and greater gender disparities in emerging nations (Filmer, 2000). Insufficient credit markets and low wages make it difficult to fund educational initiatives even when the benefits outweigh the expenses. Even after adjusting for income, parents with less education are less likely to educate their children. Parents with less education may value education less, have less academic ability, or be less able to offer supplementary inputs to learning. Furthermore, a lack of community resources in impoverished regions frequently leads to lower-quality schools, decreasing educational returns, and discouraging enrollment (Neto et al., 2022). Finally, in fragmented labor markets, the returns on education in impoverished, distant regions may be insufficient to deter educational investment (Brown and Park, 2002). Easy access to financial services in the economy has augmented the speed of economic development through financial development, human capital accumulation, efficient reallocation of economic resources, and investment. Furthermore, financial inclusion helps poor people foster their investment into productive investment and allows them to transform people into the workforce for the economy (Aghion and Bolton, 1997; Beck et al., 2007; Allen et al., 2016). In the state of financial inclusion, education has an important role in helping individuals access and use appropriate formal financial products. Lower levels of financial inclusion are associated with lower levels of financial literacy (Atkinson and Messy, 2013).

The destructive effects of poverty have lagged the economy to achieve the sustainable development goal (SDGs). Thus, over the past few years, especially developing nations have initiated several measures for lessening the process of poverty inclusion and eradication. Furthermore, a growing number of researchers and academicians have studied in exploring the key macro determinants that are responsible for poverty augmentation and reduction in the economy (Hatemi-J and Uddin, 2014; Borja, 2020; Saidu and Marafa, 2020; Aracil et al., 2021; Musakwa and Odhiambo, 2021). Considering the existing literature, several macro factors revealed their positive contribution, such as financial development, institutional quality, remittances, and investment in education, among others. The motivation of the study was to gauge the impact of investment in education on poverty reduction in the process of financial inclusion as meditating variable in the empirical model. The study considered panel data econometrical tools including panel unit root tests following Pesaran (2007), panel cointegration test following Pedroni (2004) and Westerlund (2007), variable coefficient elasticity was explored by implementing GMM (Arellano and Bond, 1991) and system-GMM estimation (Blundell and Bond, 1998), and directional causality with Toda–Yamamoto causality test. Study findings revealed that government investment in education and easy access to financial products and services positively assist in lessening the degree of poverty in the economy. It suggests that affordable education increases population enrollment into formal education and allows higher-earning possibilities, eventually reducing poverty. Moreover, access to financial benefits in the form of using the offered financial products and services in the formal financial institutions increases savings propensity among households, thus accelerating capital accumulation in the economy, eventually allowing households to bring them out of poverty with higher levels of consumption (Shen and Li, 2022).

The contribution of the study to the existing literature is as follows. First, the role of education in poverty elimination has been extensively investigated in the literature, especially for developing nations. According to the existing literature, researchers have been extensively considering “secondary years of schooling” as a proxy for education in empirical investigation with reference to measuring the education contribution in the empirical assessment. In this study, we have considered government investment in education as a proxy; the motivation for selecting this proxy is the possible linkage between educational investment and human capital development. It is because poverty reeducation is immensely guided by human capital accumulation. Second, the consideration of financial inclusion in the empirical assessment explores the role of easy access to financial products and services in managing the poverty level in the economy.

The remaining structure for the paper is as follows, apart from the Introduction in Section 1: A pertinent literature survey and a summary of that are exhibited in Section 2. Section 3 deals with variable definition and methodology of the study in detail. Empirical model estimation and interpretation is explained in Section 4, and finally, Section 5 contains the summary of the findings of the study with concluding remarks.

2 Literature Review and Theoretical Development

2.1 Nexus Between Education and Poverty

Developing nations have been significantly exposed to higher poverty levels with lower education facilities, implying that the incapacity to ensure substantial earnings due to knowledge-based skills eventually dragged households below the poverty level (Filmer, 2000; Serneels and Dercon, 2021). Furthermore, scarcity of economic resources in lower and lower-middle-income nations has detrimental impacts on education engagement and discourages enrollment in education. A growing number of empirical studies have advocated the positive effects of education on wealth creation by individuals and society, see Morgan and David (1963), Gregorio and Lee( 2002), Hofmarcher (2021), and Brunello et al. (2007). The proposition of education-led income has guided researchers in literature to investigate the hypothesis of investment in education which may reduce poverty in the economy. The nexus between education and poverty has been extensively investigated in empirical studies but has yet to establish conclusive evidence. This implies that two-line evidence was available in the literature: either a negative or neutral relationship between education and poverty. The first line of negative association that is an investment in education has augmented the speed of poverty reduction in the economy; in literature, a growing number of studies documented the said association, see, for instance, Tilak, (2002), Bonal (2007), Tilak (2007), Njong (2010), Awan (2011), and Thapa (2013). Thus, education is a critical instrument for preventing and alleviating poverty.

Bharit and Dhongde (2021) performed a study to explore insight into the impact of education and poverty reduction in the United States. The study utilized household survey data for the period 2018–2021. The study detected adverse statistically significant influences are running from education to poverty reduction in different states. Khan et al. (2019) studied the nexus between poverty and education by taking household data from central banks. A binary logistic regression test showed that education level reduces poverty, implying that education level has a significant negative connection with poverty.

Moreover, studies demonstrate that individuals with middle and above standard education are wealthier than those with primary or below standard education. Thus, it is said that greater education leads to higher income. Another study conducted by Lupeja and Gubo (2017) assessed the connection between secondary education and poverty alleviation in Tanzania. The study considered the human capital hypothesis, which states that secondary school helps people obtain jobs and reduce poverty by utilizing a cross-sectional survey to identify elementary and secondary school graduates in Mvomero District, Tanzania. The findings documented that secondary education in Tanzania may help reduce poverty by obtaining better employment and living more prosperous lives.

Arsani et al. (2020) conducted a study explaining the impact of education on poverty reduction and health by utilizing two-stage OLS. Study findings detected that the government initiatives for primary and secondary education development, assist in elucidating the level of poverty in the economy. Hofmarcher (2021) investigated the impact of education measured by schooling on poverty reduction in European countries. The study disclosed that years of schooling assist in reducing the poverty level and accelerating the scope of income generation, eventually supporting the enhancement of the standard of living. Furthermore, the study documented the positive role in increasing the supply of skilled workforce in the economy. The second line of empirical studies documented no effects of education on poverty reduction (Harber, 2002).

2.2 Nexus Between Financial Inclusion and Poverty

Financial inclusion (FI) promotes people’s ownership of transaction and savings accounts, payment facilities, credit, and remittances improving individual and family welfare by increasing entrepreneurial proclivities, women’s empowerment, education investment, and risk mitigation. The impact of FI on poverty in the contest for financial development can be observed directly and indirectly. Indirect influences, FI contributes to poverty reduction by increasing access to credit, insurance, and other financial services, which offer resources for everyday transaction requirements related to consumption, investment, and overall economic development (Rajan and Zingales, 1998). The indirect channel describes FI aids the poor over time by creating jobs and increasing government expenditure on health, education, and social protection (Abosedra et al., 2016).

Financial inclusion, achieved via microcredit to low-income families, is expected to help alleviate poverty, see, for example, Karlan and Zinman (2010) and Imai et al. (2014). Moreover, microcredit, a means of financial inclusion, has been shown to improve household income (Burgess et al., 2005), employment (BRUHN and LOVE, 2014), expenditures (Dupas and Robinson, 2013), and savings (Brune et al., 2016). Access to financial services such as microcredit may help families mitigate socioeconomic risk by empowering women, easing credit restrictions, purchasing essential inputs and assets, and assisting them in meeting some unexpected expenses on time (Kulb et al., 2016). Additionally, it empowers the poor to take control of their life and avoid less desired industrial employment and precarious wage labor by financing microbusinesses, increasing family income, and smoothing household consumption. This propoor objective is bolstered by Yunus’s Grameen Bank’s success in Bangladesh. Results demonstrate that financial inclusion may positively impact welfare, going beyond its financial advantages to the economy (Grohmann et al., 2018).

Financial inclusion seems to have become a policy priority in both emerging and developed economies, even though it was first seen as a means of relieving poverty and promoting economic growth (Onaolapo, 2015; Okoye, 2017). In empirical literate, the consensus is that economic growth is guided by strong financial development (Rajan and Zingales, 2003); as a result, most developing country governments have been promoting financial inclusion1 as a policy goal, especially for those who are ignored by formal sector institutions (Qamruzzaman et al., 2019). Promoting financial inclusion and financial literacy are obvious in the economy (Tambunan, 2015). Lack of financial knowledge results in excessive indebtedness, inefficient allocation of capital, the lack of clarity about the benefits of investment in productive activities, and the acquisition of assets or children’s education (Barua et al., 2016; Birochi and Pozzebon, 2016). On the other hand, the lack of information coupled with the limited penetration in the financial system encourages informal financial services (Zins and Weill, 2016).

Referring to the nexus between financial inclusion and poverty reduction, a growing number of studies in literature documented that the level of poverty has been reduced with easy access to the formal financial system. The study by Jalilian and Kirkpatrick (2002) established a positive association between financial services used by households with poverty reduction in 42 developing countries. Pradhan (2010) documented the positive association between financial inclusion and poverty reduction during 1951–2008 in India based on economic growth. Lal (2018) disclosed a positive impact running from financial inclusion to poverty reduction through cooperative banks during 2015 in India. Again, Inoue (2019a) shows that financial inclusion positively impacts poverty reduction in India’s public sector during 1973–2004. Koomson et al. (2020) indicate that financial inclusion positively correlates with poverty reduction based on financial inclusion indicators in Ghana during 2016–17. Nwankwo et al. (2013) discovered that the accessibility of microfinance, particularly in rural areas, benefits rural communities by offering loans for farming. Increasing the amount of agricultural output would increase the country’s per capita GDP and alleviate poverty.

The second line of conclusion that is adverse association sees, for instance, Manji (2010). Easy access to financial products and services (such as credit cards, ATMs, and internet banking) through the financial innovation adaption has detrimental consequences in a society that increases indebtedness and income inequality disparity (Lyons and Hunt, 2003). Demirgüç-Kunt et al. (2008) argued that increased financial exposure could exacerbate income disparity between beneficiaries and nonrecipients in the near term; thus, a more effective strategy would be to change the focus from improving money for the poor to improving finance for everyone. Furthermore, in a study, Inoue (2019a) established that financial inclusion have no impact on poverty reduction in the private sector of India during 1973–2004.

2.3 Motivation and Hypnotized Conceptual Model

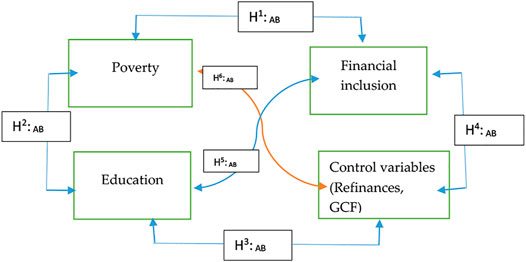

The impact of poverty and key determinants of poverty level reduction has been extensively investigated. However, the study’s motivation is not to gauge the attributes of poverty reduction but rather to evaluate the impact of government investment in education and financial inclusion on poverty reduction by employing system-GMM estimation and directional causality through a non-Ganger causality test. The following hypotheses conceptual model is to be implemented for elasticity estimation and hypothesis testing: (see, Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. Conceptual and hypnotized model for hypothesis testing. H1: AB poverty Granger causes financial inclusion and vice-versa.

H2: AB: Poverty Granger causes education and vice-versa.

H3: AB: Education Granger causes control variables and vice-versa.

H4: AB: Financial inclusion Granger causes control variables and vice-versa.

H5: AB: Education Granger causes financial inclusion and vice-versa

H6: AB: Poverty Granger causes control variables and vice-versa.

2.4 Theoretical Development: The Interlinkage Between Education, Financial Inclusion, and Poverty

As a human condition, poverty has kept the vast majority of the world’s population from having the freedom to establish a good life for generations. Eighty-four percent of the world’s population was still living in abject poverty at the start of the 19th century (Bourguignon and Morrisson, 2002). From an initial focus on inter-personal income inequalities, development theory has gradually shifted its attention to the evaluation of specific groups, with a particular emphasis on the bottom of the income distribution. More and more studies have focused on the economic causes of poverty and its effects on individuals and society (Sachs, 2005). Due to a fragile industrialization process in densely urbanized areas, the intensity of poverty in LDCs has been exacerbated by very low wages and meager labor conditions, resulting from a slow and noninclusive growth process in advanced countries and more recently also of the progressive expulsion from the production of unskilled workers. A serious challenge to human survival in contemporary times is poverty, particularly in emerging countries. The millennium development agenda, which aims to cut poverty in half by 2015, demonstrates the worldwide commitment to guaranteeing humanity’s living standards. In all of its forms, education is one of the most important aspects in attaining long-term economic growth via human capital investment (Omoniyi, 2013).

Education lays the groundwork for poverty eradication and economic prosperity. It is the foundation upon which much of the residents’ economic and social well-being is constructed. Education is critical for economic efficiency and social consistency because it increases the value and efficiency of the labor force, so lifting the poor out of poverty. Education boosts the labor population’s total productivity and intellectual flexibility and enables a nation to compete in a global market defined by rapidly changing technology and manufacturing practices. Education promotes self-awareness, enhances life quality, and increases productivity and creativity, fostering entrepreneurship and technical developments. Furthermore, it performs critical responsibilities in ensuring economic and social growth, improving income distribution, and perhaps rescuing individuals from poverty.

Financial inclusion, defined as the use of formal financial services, is a characteristic of financial development that garnered considerable public and academic interest in the early 2000s, owing to study results linking poverty reduction to financial exclusion (Sharma, 2016; Kim et al., 2018; Makina et al., 2019). Financial inclusion entails providing people and companies with access to various appropriate financial services and inexpensive financial products that fulfill their requirements in transactions, payments, savings, credit, and insurance, among others. Formal financial inclusion begins with a deposit at a bank or other financial service provider. It continues with making and receiving payments and storing and saving money (Babajide et al., 2015). Additionally, financial inclusion entails easy access to credit from official financial institutions and the usage of insurance products that protect against financial hazards such as wildfire, earthquake, flood, or crop loss, among others (Seko, 2019).

It is considered that financial inclusion promotes economic development, hence eliminating poverty and inequality. Financial inclusion is demonstrated in the phenomena of financial penetration among the general population, easy access to credit, and the community’s use of financial services to support their company or occupation. Following that, the growth components are modified using a variety of metrics that describe the economic structure, including gross domestic product, unemployment, inflation, investment, infrastructure, population, and labor. Meanwhile, poverty and inequality are quantified using the proportion of the impoverished population relative to the overall population and the Gini index to measure income distribution disparity. Financial inclusion, compared to other variables or indicators, has a more customizable measurement approach based on the conceptualization of the three variables. It reflects the applicability of data in the field and emphasizes the simplicity of accessing financial services (Kim et al., 2018; Makina et al., 2019).

3 Data and Methodology of the Study

3.1 Model Specification

The motivation of the stud is to reinvestigate the role of government investment in education in reducing the poverty level by taking a panel of lower and lower-middle-income countries for the period 1995–2018 through the mediating effects of financial inclusion. By considering the empirical association, the following generalized empirical equation is to be tested to evaluate the effects of education on poverty reduction:

where Povt denotes the level of poverty, Edu explains the government investment in education, Fin_incl for financial inclusion, and the lists of control variables represented by X∗, the subscripts i denotes for cross-section and t for the time in the data set. After transformation with natural logarithm, the aforementioned Equation 1 can be reproduced for gauging the long-run association in empirical assessment in the following manner:

3.2 Variables Definition and Descriptive Statistics

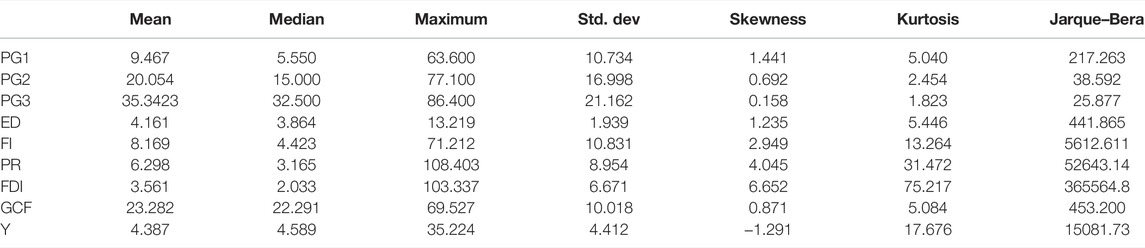

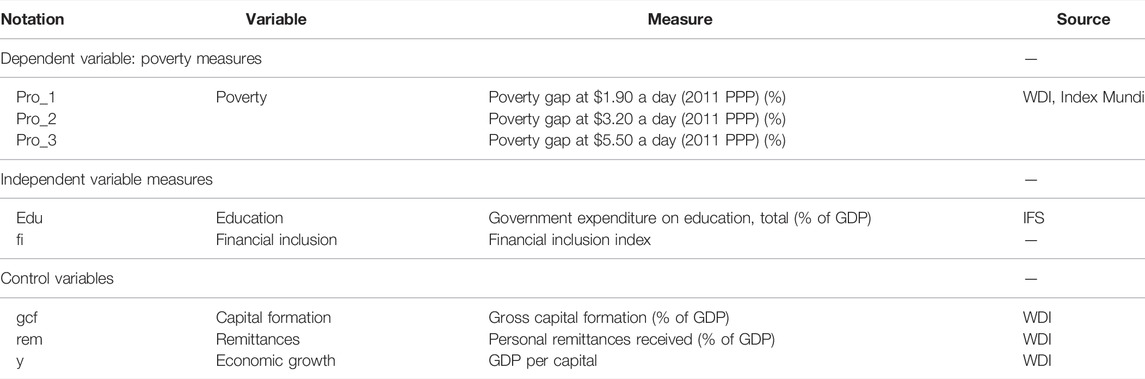

The study utilized annualized data for 1995–2018 with a panel of 68 nations representing lower and lower-middle-income counties. All the data were extracted from the world development indicator (WDI) published by the World Bank (World Bank, 2021) and international financial statistics (IFS) published by the IMF (IMF, 2018). All the variables were transformed into a natural logarithm before empirical estimation. The descriptive statistics of research variables is displayed in Table 1. The mean value of poverty is 9.467 with a standard deviation of 10.734, indicating the range between -1.274 and 18.152. The maximum value of the poverty proxy is 63.600. The mean value of education is 4.161 with a standard of 1.939, suggesting the range of 2.231–6.0912. The maximum value of education is 13.219.

3.2.1 Poverty

Absolute poverty defines specified minimum levels of commodity bundles that remain constant throughout time, and people whose income or spending falls below these minimal criteria are deemed poor. On the other hand, relative poverty compares the well-being of individuals with the fewest resources to that of the rest of the society/country without necessarily stating a minimum criterion in terms of bundles of goods/services. Individuals (especially the destitute) must determine what they perceive to be a good or minimum sufficient level of life. Transitory poverty is fleeting, ephemeral, and brief in duration, while chronic poverty is long-term, persistent poverty with mostly structural reasons. Poverty measures include those that emphasize the prevalence, depth, and severity of poverty. The prevalence of poverty is often assessed by setting a poverty line. This line distinguishes the poor from the nonpoor; hence, how this line is drawn has a significant impact on our view of poverty and, potentially, the policies devoted to its elimination. The income per capita, real disposable income, and expenditure are often employed as poverty measures. However, spending is often preferred over income owing to the issue of income underreporting. In the empirical literature, poverty is measured by several variables, including the percentage of individuals with less than US$1.9 income per day (motaghi et al., 2020), the average income shortfall of a poor individual from the poverty line ($1.25 a day) (Naceur et al., 2016). For exploring in-depth insight regarding the nexus between education, financial inclusion, and poverty, study considered a list of three proxies of misusing poverty in the empirical assessment.

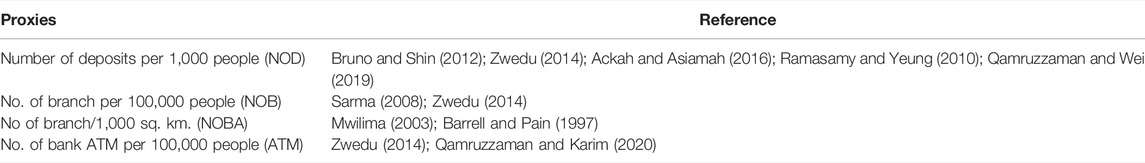

Financial inclusion can be defined as the related availability and the easiness of the financial service to everyone, including households and financial institutions, interaction with appropriate, affordable, and timely financial products and services. Financial inclusion vastly looks at the unbanked underbanked and directs sustainable financial services to society, especially in the rural area. More inclusive financial systems have been linked to stronger and more sustainable economic growth and development. Thus, achieving financial inclusion has become a priority for many countries across the globe. Referring to financial inclusion measures, the empirical literature has produced several indicators. However, in this study, we considered the financial inclusion index (see Table 2 for proxies for financial inclusion) rather than a single indicator.

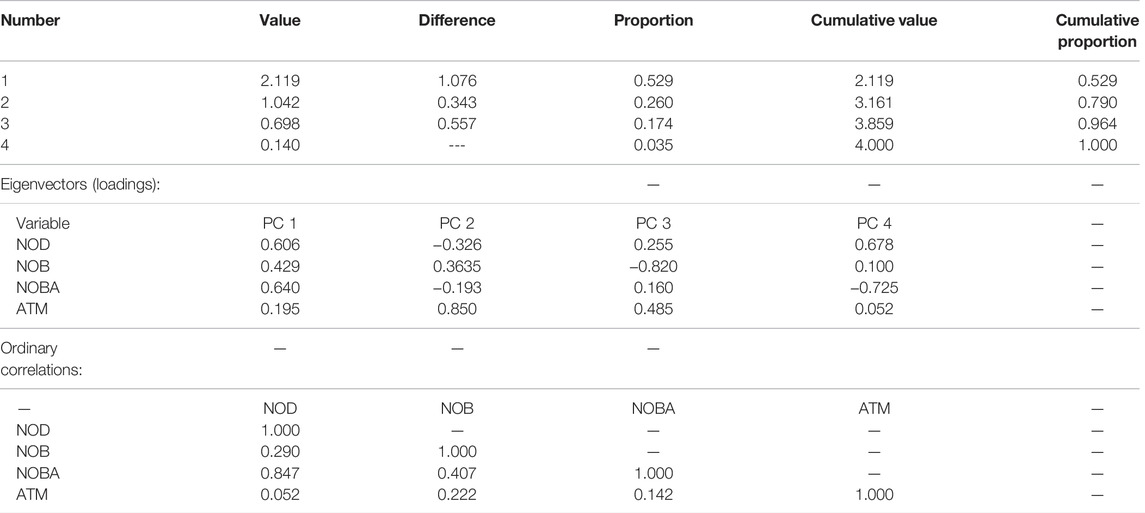

The study applied principal component analysis (PAC) for constructing the financial inclusion index (FI, hereafter). The results of PCA are displayed in Table 3

Apart from dependent and independent variables, the study considered a list of control variables extensively used in the study focusing on poverty reduction. Control variables include received personal remittances, foreign direct investment inflows, gross capital formation, and economic growth. The proxies of the respective variables are displayed in Table 4. All the variables were transformed into a natural logarithm before empirical estimation. An advantage of logarithmic transformation is that regression coefficients still have a simple interpretation in terms of multiplicative effects.

3.3 Estimation Strategy With Econometric Methods

3.3.1 Cross-Sectional Dependency Test

The cross-section dependence test is critical in panel data empirical research, particularly when representative nations have similar economic features, such as emerging countries, growing economies, and transition countries. A similar economy is vulnerable to the impacts of any shock in other countries due to trade internationalization, financial integration, and globalization. Consequently, cross-sectional dependency analysis is often needed in empirical research using panel data. According to the existing literature number of CSD, tests have emerged and applied for detecting the presence of common dynamics in research units, such as LMBP, the test was offered by Breusch and Pagan (1980), and the test statistics can be deceived with the following equation:

where

The empirical model with larger N relative to T, CDlm estimation incapacity to manage this issue and resolve the limitation in CFlm, Pesaran (2006) offered the following CD test for the situation with larger N than T:

Finally, Pesaran et al. (2008) familiarized the improved version of the CDlm test known as the bias-adjusted LM test, and the test statistics can be derived using the following equation:

where k refers to the number of regresses,

3.3.2 Panel Unit Root Tests

The study performed several unit root tests to discover the properties of the variable, especially with cross-sectional dependency. Second-generation panel unit root tests introduced by Pesaran (2007), which are commonly known as CADF and CIPS and have been extensively utilized, see, for instance, Khan et al. (2018), Qamruzzaman et al. (2018), Jia et al. (2021), and Qamruzzaman (2021). The Dickey–Fuller sectional augmented statistics (CADF) can be expressed as:

where

where the parameter

3.3.3 Panel Cointegration Test

The present research used several panel cointegration tests following Pedroni (2004), Pedroni (2001), and Kao (1999), and the bootstrap panel cointegration method developed by Westerlund (2007) to find the evidence of a long-run relationship between variables. The bootstrap panel cointegration technique is advantageous if each cross-section is composed of condensed time series. Because traditional methods do not take CD into account, they accept the null hypothesis of no cointegration even in the presence of CD. In order to generate the test statistics by implementing the panel cointegration test with an error correction environment, the following equation is to be considered:

The second step involves estimating the error correction parameter by executing the following equation:

The third step for panel statistics estimation:

3.3.4 GMM and System-GMM Estimation

To evaluate the elasticity of education and financial inclusion on poverty, the study employed generalized system methods of moments (SGMM, hereafter). The motivation behind selecting SGMM is that the conventional fixed effect estimator is not relievable and unbiased in the given situation where cross-sectional units are higher than the period (Nickell, 1981). The instrumental variables approach and generalized method of moments have been extensively used in literature. However, a certain limitation arises when dynamic panel autoregressive coefficient units are 0 which is the weak instrumental variable problem. To overcome the present limitation in instrumental variables estimator and GMM, the novel GMM was familiarized by Arellano and Bover (1995) and further development was initiated by Blundell and Bond (1998). This approach is capable of estimating reliability and consistency in all circumstance that is the issue of weak instruments, supports asymptotically, and relaxation from initial validation constraints.

The generalized specification of the system-GMM at a level and after the first difference is as follows:

Difference form:

3.3.5 Toda–Yamamoto Granger Causality Test

Finally, the study implements a non-Granger causality test following the causality framework offered by Toda and Yamamoto (1995) for exploring the directional association between government investment in education, financial inclusion, and poverty reduction. The proposed non-Granger causality test can resolve the existing problem with the conventional causality test. Conventional casualty tests are based on F-statistics and produce spurious outcomes with variable integration issues (Ganlin, 2021; Liu and Qamruzzaman, 2021; Muneeb, 2021; Yang et al., 2021). Toda and Yamamoto (1995) detect causal association with the modified Wald test to restrict a VAR(k) which is based on vector autoregressive approach at level (Q = Y + Kmax) with correct VAR order K and d extra lag, where d represents the maximum order of integration of data series:

4 Model Estimation and Interpretation

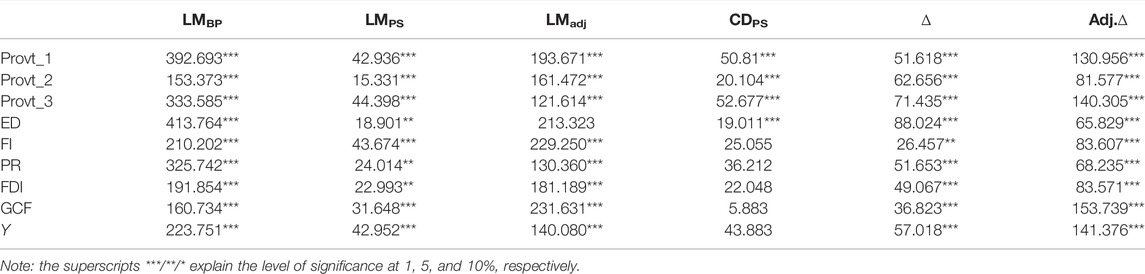

The study begins with a preliminary assessment for detecting the presence of cross-sectional dependency by employing the proposed CSD test framework following Breusch and Pagan (1980), Pesaran (2004), Pesaran (2006), and Pesaran et al. (2008) with the null hypothesis of cross-sectional independence. The results of CSD tests are displayed in Table 5. It is apparent that all the test statistics are statistically significant at a 1% level, implying the rejection of the null hypothesis which alternatively confirmed the sharing of common dynamics among research units. Furthermore, slop of homogeneity was investigated by utilizing the proposed framework by Hashem Pesaran and Yamagata (2008), and test statistics disclosed heterogeneous properties in empirical estimation.

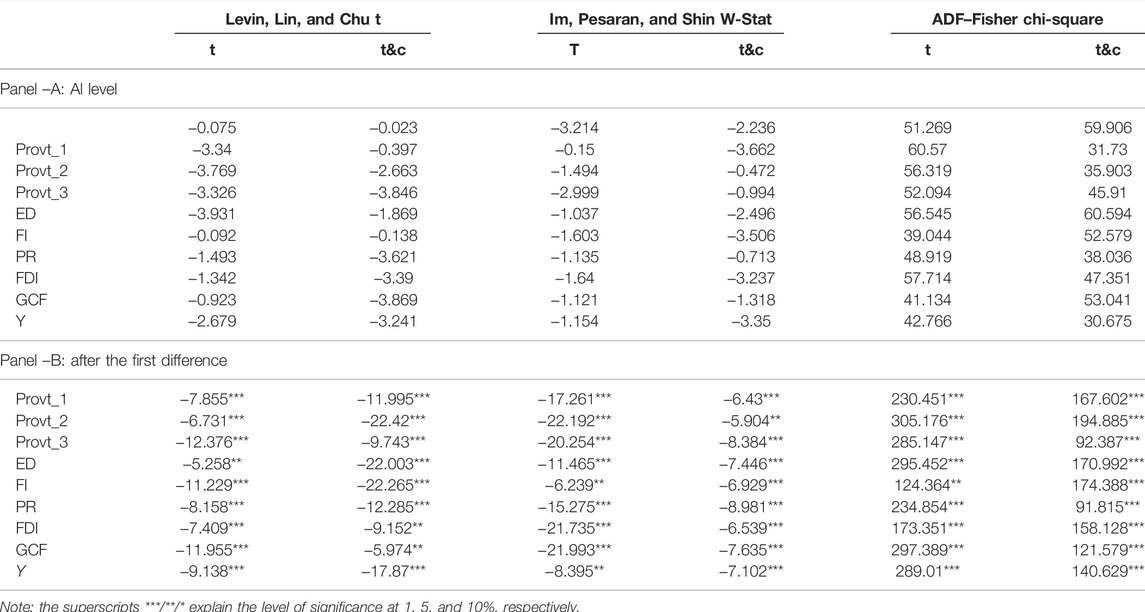

Next, variables’ stationary properties were evaluated by employing both first- and second-generation panel unit root tests. The results of first-generation unit root tests following Levin et al. (2002), Im et al. (2003), and Moon and Perron (2004) are reported in Table 6. With reference to test statistics: all the variables are stationary after the first difference, and neither of the variables were exposed to stationary after the second difference.

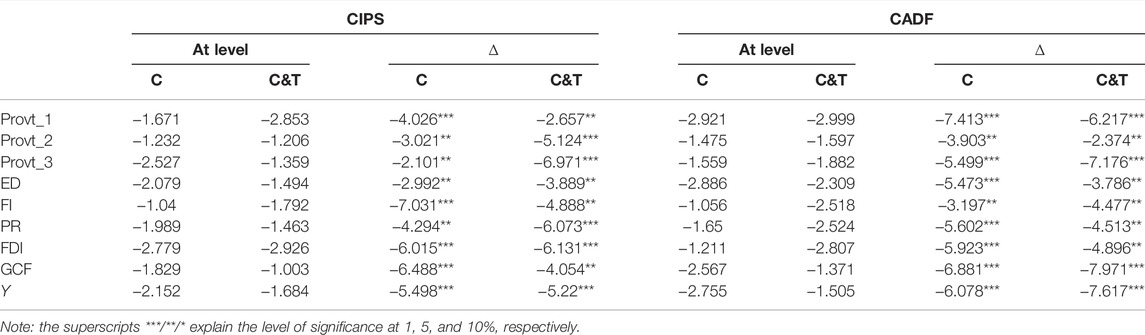

Furthermore, taking into account the presence of cross-sectional dependency, the study performed second-generation unit root tests proposed by Pesaran (2007), widely known as CADF and CIPS. The results of CADF and CIPS exhibits are shown in Table 7. Taking into account the test statistics of CADF and CIPS, it is apparent that all the variables are stationary after the first difference.

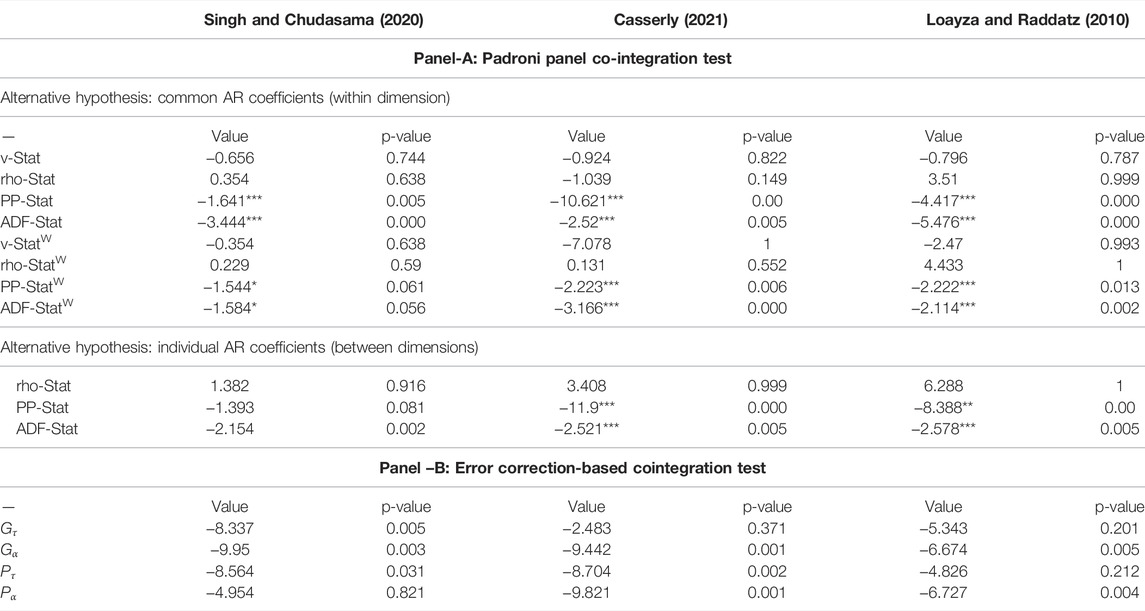

The long-run relationship between government expenditure on education, financial inclusion, and poverty reduction in lower and lower-middle-income countries was investigated through a panel cointegration test following Pedroni (2004), Pedroni (2001), Kao (1999), and Westerlund (2007). Table 8 displays the results of long-run association in empirical model estimation. Panel-A of the table reports that the Padroni cointegration test consists of eleven test statistics, according to the test statistics. Statistical significance suggests the rejection of the null hypothesis of noncointegration since the majority of the test statistics are statistically significant. The conclusion of the long-run cointegration in the empirical equation is valid for all three model execution. The results of the error correction-based panel cointegration test are displayed in the panel–B of Table 8. The study documents that the test statistics for group and panel are statistically significant at a 1% level, implying the confirmation of the cointegration association between education, financial inclusion, and poverty reduction.

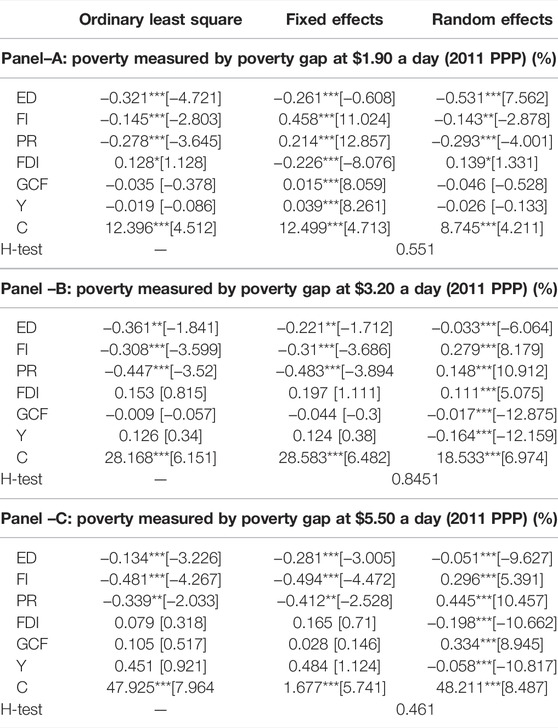

Before implementing target estimation, the study executed baseline model estimation with OLS, random effects and fixed effects models, and empirical output, and the results are displayed in Table 9. With reference to the target variables: education and financial inclusion. Findings of the study documented a negative statistically significant association with poverty reduction, and this relationship is valid for all three empirical assessments. The Hausman test statistics established baseline estimation with fixed effects OLS is efficient in deriving the variables elasticities on poverty. According to FE estimation, a 10% growth in government expenditure on educational development can decrease poverty by 2.61% in the model (Singh and Chudasama, 2020), and 2.21% in the model (Casserly, 2021), and 2.81%, respectively. Study findings suggest that government strategic investment in education positively assists society in eradicating and mitigating the vicious circle that is improving the standard of living and releasing from the poverty line. For financial inclusion impact on poverty reduction, the negative statistically significant linkage was detected, specifically the growth in unbanked population into formal financial system offers households and society for earning opportunity and increase the ability for future consumption with investment. Moreover, the effects of easy access to financial services and products motivate the population for savings propensity and increase purchasing power in the future, which eventually supports the household in releasing from the poverty level (Miao and Qamruzzaman, 2021; Zhuo and Qamruzzaman, 2021).

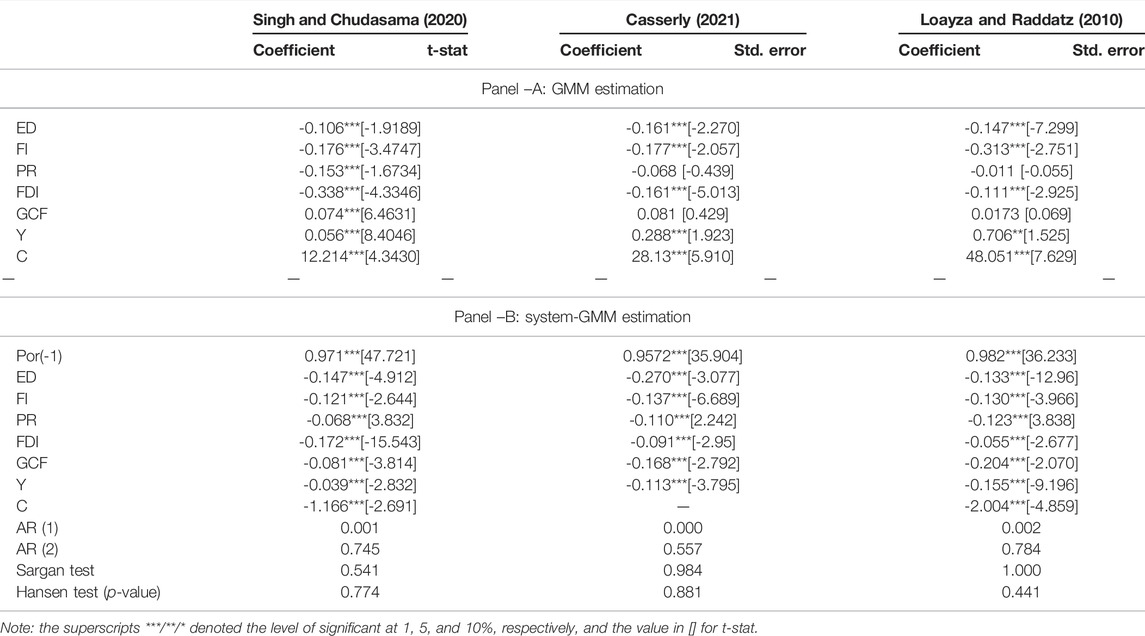

The following section deals with model estimation with GMM and system-GMM estimation. Their results in Table 10 consist of panel for GMM output and panel B for system-GMM. Furthermore, the model (Singh and Chudasama, 2020) considered poverty measured by the poverty gap at $1.90 a day, the model (Casserly, 2021) with the poverty measured by the poverty gap at $3.20 a day, and the model (Loayza and Raddatz, 2010) poverty proxies by the poverty gap at $5.50 a day, respectively.

For the nexus between education and poverty, with reference to empirical output with GMM estimation, the study documents statistically significant damaging effects running from government investment in education and poverty in all three model estimations. More precisely, a 10% increase in the level of education through government investment can result in decreasing the trend in the poverty gap by 1.066% in the model by Singh and Chudasama (2020), by 1.610% in the model by Casserly (2021), and 1.470% in the model by Loayza and Raddatz (2010). Furthermore, empirical model estimation with system-GMM, the study documented a negative statistically significant association in the model by Singh and Chudasama (2020) with a coefficient of -0.1472, in the model by Casserly (2021) with a coefficient of -0.2706, and in the model by Loayza and Raddatz (2010) with a coefficient of -0.1339. Study findings suggest that a 10% growth in government investment in education can augment the poverty reduction circumstance by 1.339–2.706% in three empirical model estimations. Study findings suggest that positive attitudes in educational investment in the economy augment the household capacity to increase their standard of living, thus eventually reducing the trend of poverty creation.

Regarding the nexus between financial inclusion and poverty, empirical estimation with GMM estimation revealed a negative statistically significant linkage. Specifically, a 10% development in financial inclusion that is more unbanked household’s inclusion into the formal financial system accelerate the level of poverty in the economy by 1.766% in the model by Singh and Chudasama (2020), by 1.771% in the model by Casserly (2021), and 3.133% in the model by Loayza and Raddatz (2010). Additionally, the elasticity of financial inclusion on poverty in the system-GMM documented a negative statistically significant linkage in all three assessments. Precisely, according to coefficients, a 10% growth in financial inclusion in the economy can result in decreasing the present state of poverty level by 1.217% in the model by Singh and Chudasama (2020), 1.377% in the model by Casserly (2021), and by 1.307% in the model by Loayza and Raddatz (2010), respectively. Study findings suggest that the inclusion of the unbanked population into the formal financial system open an avenue for earning opportunity capital accumulation for future investment and consumption, which eventually supports household and the economy in lessening the prospect of poverty inclusion. Study findings align with the existing literature works, see, for instance, Omar and Inaba (2020), Inoue (2019b), Mohammed et al. (2017), and Chibba (2009).

Moreover, regarding the impacts of control variables on poverty reduction, study findings documented a negative statistically significant association between personal remittance, inflows of foreign direct investment, and poverty reduction in all three model assessments. In contrast, positive statistically significant effects are running from gross capital formation and economic growth in lower and lower-middle-income countries.

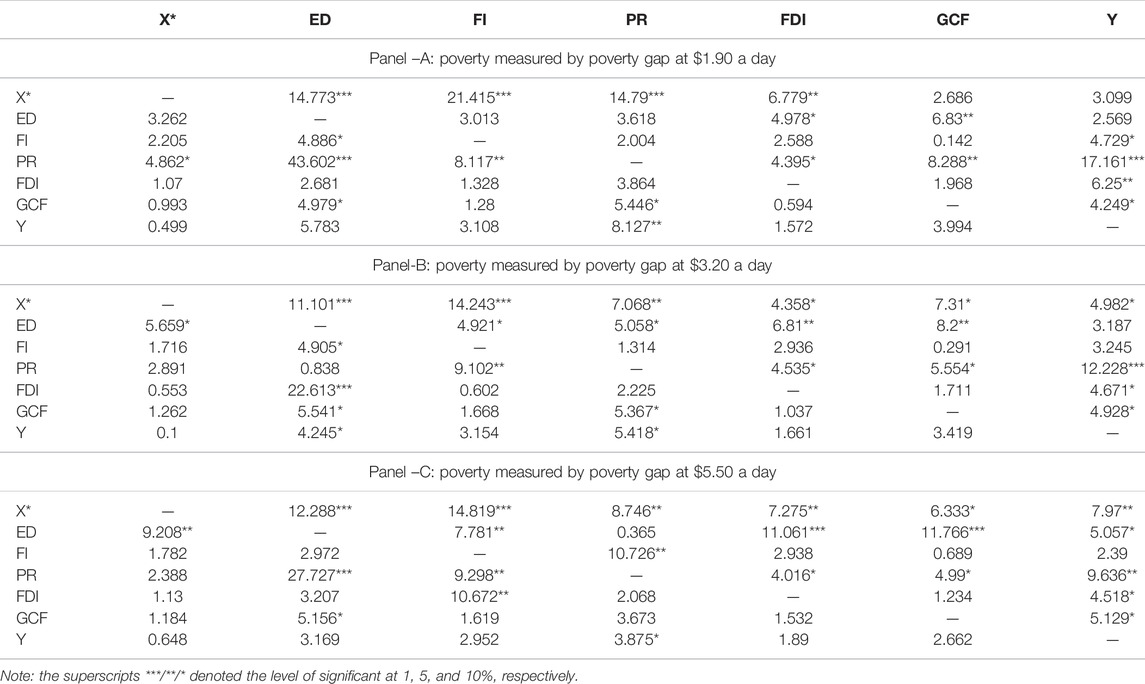

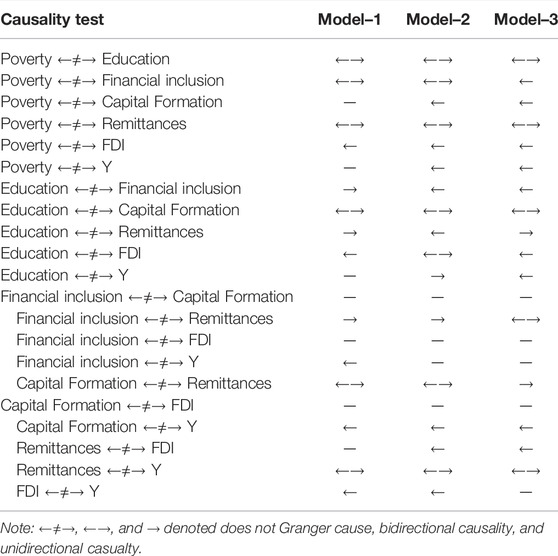

Next, the study moved in detecting the directional association by performing a causality test following the no Granger causality framework offered by Toda and Yamamoto (1995) in the panel form. The causality test results are displayed in Table 11 with three output panels based on different poverty proxies. Considering the causality test, it is apparent that several causal effects are available among research units. The summary of directional casualties is presented in Table 12.

With reference to the summary of the causality test, we found several directional associations among research units; however, we are focused on evaluating the causality between education, financial inclusion, and poverty reduction in lower and lower-middle-income countries. The causality test results documented the feedback hypothesis available in explaining the causality between investment in education and poverty reduction in lower and middle-income countries, which aligns with existing literature Citak and Duffy (2020). Furthermore, the bidirectional causality was found on poverty reduction and financial inclusion [Poverty←→FI], suggesting that the inclusion of the population into the formal financial system plays a role in reducing poverty by allowing higher capacity in future consumption.

5 Discussion

The relationship between investment in education and poverty reduction has exposed a negative statistically significant association. It aligns with the existing literature, for instance, Khan et al. (2019) and Omar and Inaba (2020). People may enhance their health and productivity by obtaining a higher level of knowledge with better education. Education has always been a critical factor in determining an individual’s ability and capacity to perform. Moreover, higher capacity allows a higher degree of earning opportunity. Furthermore, education has the potential to break the vicious cycle of poverty and social marginalization, so improving the overall quality of life and social welfare for all people (Ustama, 2009). Increased household education will not only benefit production and income, but it may also increase productivity among other family members by encouraging them to become educated and trained. A household with a higher level of education is less likely to expose to risk, implying that the likelihood of poverty in the economy is substantially reduced when the householder has a higher degree of education. An increase in education for households may enhance the productivity of others in the family by encouraging them to acquire training and/or skills and positively impacting production and wages (Dietrich and Weber, 2018).

As education increases, impoverished people decrease since education equips individuals with knowledge and skills and leads to better earnings. Education directly reduces poverty by raising people’s earnings and allows access to basic needs to become simpler and decreasing human poverty. Furthermore, investment in education accelerated human capital development with greater national productivity which will eventually lead to a poverty-free economy (Fan et al., 2000).

Financial inclusion is a multifaceted term encompassing all aspects of financial growth by ensuring that all people have inexpensive access to and use basic formal financial services. Credit, savings, insurance, payments, and remittance facilities. Without access to financial services, people often turn to high-cost informal money sources; this financial exclusion very certainly has a disproportionately detrimental effect on low-income populations. As a result, financial inclusion is critical for relieving poverty and decreasing economic disparities within a nation. Regarding the nexus between financial inclusion and poverty reduction in lower and lower-middle-income countries, study established that financial inclusion plays a critical role in poverty reduction, implying the negative statistically significant influences running to poverty reduction activities. Study findings align with existing literature works such as Ozili (2020), Omar and Inaba (2020), Inoue (2019b), Mohammed et al. (2017), and Chibba (2009). Financial inclusion can improve the poor’s financial situation and level of life while also reducing income disparity (Beck et al., 2007). Brune et al. (2011) asserted that saving enables families to improve their ability to withstand financial shocks, smooth consumption, accrue assets, and invest in health and education. Access to financial services can break the cycle of poverty for the poor by instilling a saving culture and establishing efficient and low-cost payment methods (Dixit, 2017). Sanjaya (2014) discovered that financial inclusion via microcredit programs might significantly enhance the poor’s social and economic standing.

Moreover, financial services will help decrease family budget deficits and poverty by putting money in the hands of females, particularly those who are financially uneducated (Seng, 2020). Financial inclusion has moved from regional to global policy discussion since the new millennium. Equal economic development is a common strategy for many nations to implement financial inclusion. To promote sustainable development and enhance global welfare, the United Nations has established the objective of financial inclusion among the Millennium Development Goals (MDG) (Andriamahery and Qamruzzaman, 2021; Muneeb and Ayesha, 2022; Qamruzzaman, 2022).

6 Conclusion and Policy Implications

6.1 Conclusion

The motivation of the study is to investigate the nexus between government investments in education, financial inclusion, and poverty reduction in lower and lower-middle-income countries for the period 1995–2018 with a panel of 68 nations. The study employed several econometrical tools in evaluating the effects and determining the coefficients of education and financial inclusion on poverty reduction through system-GMM estimation and directional association documented with a non-Granger framework in panel form. The findings of the study are as follows: first, the results of the CSD test and slop of homogeneity established research units share some common dynamism among them, and the heterogeneous properties are available in variables. Second, the stationarity properties of variables were detected by utilizing both first- and second-generation panel unit root tests such as LLC test, IPM test, CADF, and CIPS. Study findings revealed that all the variables are stationary either at level or after the first difference. Neither variables are exposed to stationary after the second difference. Thirdly, the long-run association between education, financial inclusion, and poverty reduction was investigated by implementing a panel cointegration test following Pedroni (2004), Pedroni (2001), and Westerlund (2007). The test statistics of Pedroni and error correction-based cointegration test established a long-run association by rejecting the null hypothesis of noncointegration. Fourth, with reference to the empirical model estimation with system-GMM, it is evident that government investment in education and access to financial services positively reduces poverty in the economy. Fifth, the directional causality established the feedback hypothesis in explaining the relationship between education and poverty reduction [ED←→Poverty] and financial inclusion and poverty [FI←→Poverty].

6.2 Policy Implications

Even though poverty is a multidimensional phenomenon, it is often assessed in terms of economic characteristics such as income and consumption. In contrast, Amartya Sen’s capacity deprivation approach to poverty assessment defines poverty as an inability to obtain certain minimal capacities rather than a question of real income (Sen, 1976). It is important to consider this disparity between people’s wages and their inabilities since the translation of real money into actual capabilities varies depending on social contexts and individual attitudes. We propose the following policy implication for poverty eradication through financial inclusion and government investment in education by considering the empirical findings.

First, education-backed poverty alleviation policies that aim at helping registered poor households need to be more targeted, which is also a common issue for public policy. The researchers plan to further refine the theoretical concepts and policy standards of poverty alleviation through education in the next steps.

Second, every person has the right to education. To get an education, people must improve their skills and talents to comprehend lesson plans and academic ideas. Most studies on poverty have revealed a strong link between education and income. Educators at educational institutions must use proper teaching-learning approaches and instructional strategies. Similarly, students must arrange their learning approaches to obtain the required academic goals. The importance of education as a human right is used to analyze how education might assist the poor, underprivileged, and marginalized elements of society to improve their living situations.

Third, financial inclusion is crucial for inclusive growth and necessary for long-term economic growth and development. Using technology to its full potential is one of the most successful strategies for integrating unbanked people into the financial mainstream. Financial inclusion is defined as responsibly and sustainably providing people and companies with usable and cheap financial goods and services that suit their requirements–transactions, payments, savings, credit, and insurance.

Fourth, financial access makes daily life easier and assists families and companies in planning for anything from long-term objectives to unforeseen crises. Individuals who own accounts are more likely to utilize other financial services, such as credit and insurance, to establish and develop enterprises, invest in education or health, manage risk, and weather financial shocks, all of which may enhance their overall quality of life.

The present study is not out of limitation because sample selection, econometrical methodology implementation, and variables inclusion in the present study might result in a different interpretation. Thus, in terms of future research direction, we would like to postulate that the inclusion of remittance inflows and good governance could be an alternative means of empirical assessment.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

MQ: introduction, methodology, and empirical model estimation; ZS: first draft preparation and final preparation.

Funding

The study has received financial support from the Institutions for Advanced Research (IAR) under project financing–IAR/2021/PUB/009.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abosedra, S., Shahbaz, M., and Nawaz, K. (2016). Modeling Causality between Financial Deepening and Poverty Reduction in Egypt. Soc. Indic. Res. 126 (3), 955–969. doi:10.1007/s11205-015-0929-2

Ackah, C., and Asiamah, J. P. (2016). “Financial Regulation in Ghana: Balancing Inclusive Growth with Financial Stability,” in Achieving Financial Stability and Growth in Africa (New york, NY: Routledge), 123–137.

Aghion, P., and Bolton, P. (1997). A Theory of Trickle-Down Growth and Development. Rev. Econ. Stud. 64 (2), 151–172. doi:10.2307/2971707

Ahmad, F., Draz, M. U., Su, L., Ozturk, I., Rauf, A., and Ali, S. (2019). Impact of FDI Inflows on Poverty Reduction in the ASEAN and SAARC Economies. Sustainability 11 (9), 2565. doi:10.3390/su11092565

Allen, F., Demirguc-Kunt, A., Klapper, L., and Peria, M. S. M. (2016). The Foundations of Financial Inclusion: Understanding Ownership and Use of Formal Accounts. J. Financial Intermediation 27, 1–30.

Andriamahery, A., and Qamruzzaman, M. (2021). Do Access to Finance, Technical Know-How, and Financial Literacy Offer Women Empowerment through Women's Entrepreneurial Development? Front. Psychol. 12 (5889), 776844. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.776844

Aracil, E., Gómez-Bengoechea, G., and Moreno-de-Tejada, O. (2021). Institutional Quality and the Financial Inclusion-Poverty Alleviation Link: Empirical Evidence across Countries. Borsa Istanb. Rev.

Arellano, M., and Bond, S. (1991). Some Tests of Specification for Panel Data: Monte Carlo Evidence and an Application to Employment Equations. Rev. Econ. Stud. 58 (2), 277–297. doi:10.2307/2297968

Arellano, M., and Bover, O. (1995). Another Look at the Instrumental Variable Estimation of Error-Components Models. J. Econ. 68 (1), 29–51. doi:10.1016/0304-4076(94)01642-d

Arsani, A. M., Ario, B., and Ramadhan, A. F. (2020). Impact of Education on Poverty and Health : Evidence from Indonesia. Edaj 9 (1), 87–96. doi:10.15294/edaj.v9i1.34921

Atkinson, A., and Messy, F.-A. (2013). Promoting Financial Inclusion through Financial Education: OECD/INFE Evidence, Policies and Practice.

Azam, M., Haseeb, M., and Samsudin, S. (2016). The Impact of Foreign Remittances on Poverty Alleviation: Global Evidence. Econ. Sociol. 9 (1), 264–281. doi:10.14254/2071-789x.2016/9-1/18

Babajide, A. A., Adegboye, F. B., and Omankhanlen, A. E. (2015). Financial Inclusion and Economic Growth in Nigeria. Int. J. Econ. financial issues 5 (3), 629–637.

Barrell, R., and Pain, N., Foreign Direct Investment, Technological Change, and Economic Growth within Europe. 1997. 107(445): p. 1770–1786.doi:10.1111/j.1468-0297.1997.tb00081.x

Barua, A., Kathuria, R., and Malik, N. (2016). The Status of Financial Inclusion, Regulation, and Education in India.

Beck, T., Demirgüç-Kunt, A., and Levine, R. (2007). Finance, Inequality and the Poor. J. Econ. Growth 12 (1), 27–49. doi:10.1007/s10887-007-9010-6

Birochi, R., and Pozzebon, M. (2016). Improving Financial Inclusion: Towards a Critical Financial Education Framework. Rev. Adm. Empres. 56 (3), 266–287. doi:10.1590/s0034-759020160302

Blundell, R., and Bond, S. (1998). Initial Conditions and Moment Restrictions in Dynamic Panel Data Models. J. Econ. 87 (1), 115–143. doi:10.1016/s0304-4076(98)00009-8

Bonal, X. (2007). On Global Absences: Reflections on the Failings in the Education and Poverty Relationship in Latin America. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 27 (1), 86–100. doi:10.1016/j.ijedudev.2006.05.003

Borja, K. (2020). Remittances, Corruption, and Human Development in Latin America. St. Comp. Int. Dev. 55 (3), 305–327. doi:10.1007/s12116-020-09299-1

Bourguignon, F., and Morrisson, C. (2002). Inequality Among World Citizens: 1820-1992. Am. Econ. Rev. 92 (4), 727–744. doi:10.1257/00028280260344443

Breusch, T. S., and Pagan, A. R. (1980). The Lagrange Multiplier Test and its Applications to Model Specification in Econometrics. Rev. Econ. Stud. 47 (1), 239–253. doi:10.2307/2297111

Brown, P. H., and Park, A. (2002). Education and Poverty in Rural China. Econ. Educ. Rev. 21 (6), 523–541. doi:10.1016/s0272-7757(01)00040-1

Bruhn, M., and Love, I. (2014). The Real Impact of Improved Access to Finance: Evidence from Mexico. J. Finance 69 (3), 1347–1376. doi:10.1111/jofi.12091

Brune, L., Giné, X., Goldberg, J., and Yang, D. (2011). Commitments to Save: A Field Experiment in Rural Malawi. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 574. Available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1904244.

Brune, L., Giné, X., Goldberg, J., and Yang, D. (2016). Facilitating Savings for Agriculture: Field Experimental Evidence from Malawi. Econ. Dev. Cult. Change 64 (2), 187–220. doi:10.1086/684014

Brunello, G., Garibaldi, P., and Wasmer, E. (2007). “Higher Education, Innovation and Growth,” in Education and Training in Europe (Oxford University Press). doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199210978.003.0004

Bruno, V., and Shin, H. S. (2012). “Capital Flows, Cross-Border Banking and Global Liquidity,” in AFA 2013 San Diego Meetings Paper.

Burgess, R., Pande, R., and Wong, G. (2005). Banking for the Poor: Evidence from India. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 3 (2-3), 268–278. doi:10.1162/jeea.2005.3.2-3.268

Casserly, C. M. (1998). African-American Women and Poverty: Can Education Alone Change the Status Quo?. 1st Edn. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781003248941

Chibba, M. (2009). Financial Inclusion, Poverty Reduction and the Millennium Development Goals. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 21 (2), 213–230. doi:10.1057/ejdr.2008.17

Citak, F., and Duffy, P. A. (2020). The Causal Effect of Education on Poverty: Evidence from Turkey. East. J. Eur. Stud. 11 (2).

Daw, T., Brown, K., Rosendo, S., and Pomeroy, R. (2011). Applying the Ecosystem Services Concept to Poverty Alleviation: the Need to Disaggregate Human Well-Being. Envir. Conserv. 38 (4), 370–379. doi:10.1017/s0376892911000506

Demirgüç-Kunt, A., Beck, T., and Honohan, P. (2008). Finance for All? Policies and Pitfalls in Expanding Access. New York, NY: World Bank.

Dietrich, A., and Weber, C. (2018). What Drives Profitability of Grid-Connected Residential PV Storage Systems? A Closer Look with Focus on Germany. Energy Econ. 74, 399–416. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2018.06.014

Dixit, V. (2017). Causality between Economic Openness, Income Inequality, and Welfare Spending in India. Asia-Pacific Soc. Sci. Rev. 17 (1), 1.

Donou-Adonsou, F., and Sylwester, K. (2016). Financial Development and Poverty Reduction in Developing Countries: New Evidence from Banks and Microfinance Institutions. Rev. Dev. Finance 6 (1), 82–90. doi:10.1016/j.rdf.2016.06.002

Dupas, P., and Robinson, J. (2013). Savings Constraints and Microenterprise Development: Evidence from a Field Experiment in Kenya. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 5 (1), 163–192. doi:10.1257/app.5.1.163

Ekanayake, E. M., and Moslares, C. (2020). Do Remittances Promote Economic Growth and Reduce Poverty? Evidence from Latin American Countries. Economies 8 (2), 35. doi:10.3390/economies8020035

Fan, S., Hazell, P., and Thorat, S. (2000). Government Spending, Growth and Poverty in Rural India. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 82 (4), 1038–1051. doi:10.1111/0002-9092.00101

Filmer, D. (2000). The Structure of Social Disparities in Education: Gender and Wealth. Available at SSRN 629118.

Ganlin, P. (2021). Innovative Finance, Technological Adaptation and SMEs Sustainability: The Mediating Role of Government Support during COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 13 (16), 1–27.

Gregorio, J. D., and Lee, J.-W. (2002). Education and Income Inequality: New Evidence from Cross-Country Data. Rev. Income Wealth 48 (3), 395–416. doi:10.1111/1475-4991.00060

Grohmann, A., Klühs, T., and Menkhoff, L. (2018). Does Financial Literacy Improve Financial Inclusion? Cross Country Evidence. World Dev. 111, 84–96. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.06.020

Harber, C. (2002). Education, Democracy and Poverty Reduction in Africa. Comp. Educ. 38 (3), 267–276. doi:10.1080/0305006022000014133

Hashem Pesaran, M., and Yamagata, T. (2008). Testing Slope Homogeneity in Large Panels. J. Econ. 142 (1), 50–93. doi:10.1016/j.jeconom.2007.05.010

Hatemi-J, A., and Uddin, G. S. (2014). On the Causal Nexus of Remittances and Poverty Reduction in Bangladesh. Appl. Econ. 46 (4), 374–382. doi:10.1080/00036846.2013.844331

Ho, S.-Y., and Iyke, B. N. (2017). Does Financial Development Lead to Poverty Reduction in China? Time Series Evidence. Jebs 9 (1), 99–112. doi:10.22610/jebs.v9i1.1561

Hofmarcher, T. (2021). The Effect of Education on Poverty: A European Perspective. Econ. Educ. Rev. 83, 102124. doi:10.1016/j.econedurev.2021.102124

Im, K. S., Pesaran, M. H., and Shin, Y. (2003). Testing for Unit Roots in Heterogeneous Panels. J. Econ. 115 (1), 53–74. doi:10.1016/s0304-4076(03)00092-7

Imai, K. S., Gaiha, R., Ali, A., and Kaicker, N. (2014). Remittances, Growth and Poverty: New Evidence from Asian Countries. J. Policy Model. 36 (3), 524–538. doi:10.1016/j.jpolmod.2014.01.009

Inoue, T. (2019). Financial Inclusion and Poverty Reduction in India. J. Financial Econ. Policy. doi:10.1108/jfep-01-2018-0012

Inoue, T. (2019). Financial Inclusion and Poverty Reduction in India. Jfep 11 (1), 21–33. doi:10.1108/jfep-01-2018-0012

Jalilian, H., and Kirkpatrick, C. (2005). Does Financial Development Contribute to Poverty Reduction? J. Dev. Stud. 41 (4), 636–656. doi:10.1080/00220380500092754

Jalilian, H., and Kirkpatrick, C. (2002). Financial Development and Poverty Reduction in Developing Countries. Int. J. Fin. Econ. 7 (2), 97–108. doi:10.1002/ijfe.179

Jia, Z., Mehta, A. M., Qamruzzaman, M., and Ali, Majid (2021). Economic Policy Uncertainty and Financial Innovation: Is There Any Affiliation? Front. Psychol. 12, 1781.

Kao, C. (1999). Spurious Regression and Residual-Based Tests for Cointegration in Panel Data. J. Econ. 90 (1), 1–44. doi:10.1016/s0304-4076(98)00023-2

Karlan, D., and Zinman, J. (2010). Expanding Credit Access: Using Randomized Supply Decisions to Estimate the Impacts. Rev. Financ. Stud. 23 (1), 433–464. doi:10.1093/rfs/hhp092

Khan, M. T. I., Ali, Q., and Ashfaq, M. (2018). The Nexus between Greenhouse Gas Emission, Electricity Production, Renewable Energy and Agriculture in Pakistan. Renew. Energy 118, 437–451. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2017.11.043

Khan, M. Y., Alvi, A. K., and Chishti, M. F. (2019). An Investigation on the Linkages between Poverty and Education: A Statistical Review. Gomal Univ. J. Res. 35 (1), 44–53.

Kim, D.-W., Yu, J.-S., and Hassan, M. K. (2018). Financial Inclusion and Economic Growth in OIC Countries. Res. Int. Bus. Finance 43, 1–14. doi:10.1016/j.ribaf.2017.07.178

Koomson, I., Villano, R. A., and Hadley, D. (2020). Effect of Financial Inclusion on Poverty and Vulnerability to Poverty: Evidence Using a Multidimensional Measure of Financial Inclusion. Soc. Indic. Res. 149, 613–639. doi:10.1007/s11205-019-02263-0

Krueger, A. B., and Malečková, J. (2003). Education, Poverty and Terrorism: Is There a Causal Connection? J. Econ. Perspect. 17 (4), 119–144. doi:10.1257/089533003772034925

Kulb, C., Hennink, M., Kiiti, N., and Mutinda, J. (2016). How Does Microcredit Lead to Empowerment? A Case Study of theVinya Wa AkaGroup in Kenya. J. Int. Dev. 28 (5), 715–732. doi:10.1002/jid.3130

Lal, T. (2018). Impact of Financial Inclusion on Poverty Alleviation through Cooperative Banks. Int. J. Soc. Econ. doi:10.1108/ijse-05-2017-0194

Levin, A., Lin, C.-F., and James Chu, C.-S. (2002). Unit Root Tests in Panel Data: Asymptotic and Finite-Sample Properties. J. Econ. 108 (1), 1–24. doi:10.1016/s0304-4076(01)00098-7

Liu, J., and Qamruzzaman, M. (2021). An Asymmetric Investigation of Remittance, Trade Openness Impact on Inequality: Evidence from Selected South Asian Countries. Front. Psychol., 4022.

Loayza, N. V., and Raddatz, C. (2010). The Composition of Growth Matters for Poverty Alleviation. J. Dev. Econ. 93 (1), 137–151. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2009.03.008

Lupeja, T. L., and Gubo, Q. (2017). Secondary Education Attainment and its Role in Poverty Reduction: Views of Graduates Working in Informal Sector in Rural Tanzania. J. Educ. Pract. 8 (11), 140–149.

Lyons, A. C., and Hunt, J. (2003). The Credit Practices and Financial Education Needs of Community College Students. J. Financial Couns. Plan. 14 (2).

Magombeyi, M. T., and Odhiambo, N. M. (2017). Causal Relationship between FDI and Poverty Reduction in South Africa. Cogent Econ. Finance 5 (1), 1357901. doi:10.1080/23322039.2017.1357901

Magombeyi, M. T., and Odhiambo, N. M. (2018). Dynamic Impact of FDI Inflows on Poverty Reduction: Empirical Evidence from South Africa. Sustain. Cities Soc. 39, 519–526. doi:10.1016/j.scs.2018.03.020

Makina, D., and Walle, Y. M. (2019). “Financial Inclusion and Economic Growth,” in Extending Financial Inclusion in Africa. Editor D. Makina (Academic Press), 193–210. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-814164-9.00009-8

Manji, A. (2010). Eliminating Poverty? 'Financial Inclusion', Access to Land, and Gender Equality in International Development. Mod. Law Rev. 73 (6), 985–1004. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2230.2010.00827.x

Miao, M., and Qamruzzaman, M. (2021). Dose Remittances Matter for Openness and Financial Stability: Evidence from Least Developed Economies. Front. Psychol. 12 (2606), 696600. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.696600

Mohammed, J. I., Mensah, L., and Gyeke-Dako, A. (2017). Financial Inclusion and Poverty Reduction in Sub-saharan Africa. Afr. Finance J. 19 (1), 1–22.

Moon, H. R., and Perron, B. (2004). Testing for a Unit Root in Panels with Dynamic Factors. J. Econ. 122 (1), 81–126. doi:10.1016/j.jeconom.2003.10.020

Morgan, J., and David, M. (1963). Education and Income. Q. J. Econ. 77 (3), 423–437. doi:10.2307/1879570

motaghi, s., Ranjbar Fallah, M. R., and Ebrahimi, S. (2020). An Analytical Examination of the Effects of Financial Development on Poverty. Int. J. Finance Manag. Account. 5 (17), 107–113.

Muneeb, M. A., and Ayesha, S. (2022). The Effects of Finance and Knowledge on Entrepreneurship Development: An Empirical Study from Bangladesh. J. Asian Finance, Econ. Bus. 9 (2), 409–418.

Muneeb, M. A. (2021). The Effect of Technology and Open Innovation on Women-Owned Small and Medium Enterprises in Pakistan. J. Asian Finance, Econ. Bus. 8 (3), 411–422.

Musakwa, M. T., and Odhiambo, N. M. (2020). Remittance Inflows and Poverty Nexus in Botswana: a Multivariate Approach. J. Sustain. Finance Invest., 1–15. doi:10.1080/20430795.2020.1777786

Musakwa, M. T., and Odhiambo, N. M. (2021). The Causal Relationship between Remittance and Poverty in South Africa: A Multivariate Approach. Int. Soc. Sci. J. 71 (239-240), 37–48. doi:10.1111/issj.12260

Mwilima, N. (2003). Foreign Direct Investment In Africa, Social Observatory Pilot Project‐Final Draft Report‐FDI, Africa Labour Research Network, Labour Resource and Research Institute (LaRRI).

Naceur, S. B., Zhang, R., and Kanaan, O. (2016). Financial Development, Inequality and Poverty: Some International Evidence. IMF Work. Pap. 2016 (032), A001. doi:10.5089/9781498359283.001

Neto, I. T. M., Silva, K. L., and Guimarães, R. A. (2022). Tools Used in Nursing Education to Assess Attitudes about Poverty: An Integrative Review 00, 1–9. doi:10.1111/phn.13062

Nickell, S. (1981). Biases in Dynamic Models with Fixed Effects. Econometrica 49, 1417–1426. doi:10.2307/1911408

Njong, A. M. (2010). The Effects of Educational Attainment on Poverty Reduction in Cameroon. Int. J. Educ. Adm. Policy Stud. 2 (1), 001–008.

Nwankwo, O., Olukotu, G., and Abah, E. (2013). Impact of Microfinance on Rural Transformation in Nigeria. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 8 (19), 99. doi:10.5539/ijbm.v8n15p144

Okoye, L. U. (2017). Financial Inclusion as a Strategy for Enhanced Economic Growth and Development. J. Internet Bank. Commer. 22 (S8).

Omar, M. A., and Inaba, K. (2020). Does Financial Inclusion Reduce Poverty and Income Inequality in Developing Countries? A Panel Data Analysis. Econ. Struct. 9 (1), 37. doi:10.1186/s40008-020-00214-4

Omoniyi, M. B. I. (2013). The Role of Education in Poverty Alleviation and Economic Development: A Theoretical Perspective and Counselling Implications. Br. J. Arts Soc. Sci. 15 (2), 176–185.

Onaolapo, A. R. (2015). Effects of Financial Inclusion on the Economic Growth of Nigeria (1982-2012). Int. J. Bus. Manag. Rev. 3 (8), 11–28.

Ozili, P. K. (2020). “Financial Inclusion Research Around the World: A Review,” in Forum for Social Economics (Taylor & Francis). doi:10.1080/07360932.2020.1715238

Pedroni, P. (2004). Panel Cointegration: Asymptotic and Finite Sample Properties of Pooled Time Series Tests with an Application to the PPP Hypothesis. Econ. theory 20 (3), 597–625. doi:10.1017/s0266466604203073

Pedroni, P. (2001). Purchasing Power Parity Tests in Cointegrated Panels. Rev. Econ. Statistics 83 (4), 727–731. doi:10.1162/003465301753237803

Pesaran, M. H. (2007). A Simple Panel Unit Root Test in the Presence of Cross-Section Dependence. J. Appl. Econ. 22 (2), 265–312. doi:10.1002/jae.951

Pesaran, M. H. (2006). Estimation and Inference in Large Heterogeneous Panels with a Multifactor Error Structure. Econometrica 74 (4), 967–1012. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0262.2006.00692.x

Pesaran, M. H., Ullah, A., and Yamagata, T. (2008). A Bias-Adjusted LM Test of Error Cross-Section Independence. Econ. J. 11 (1), 105–127. doi:10.1111/j.1368-423x.2007.00227.x

Pradhan, R. P. (2010). The Nexus between Finance, Growth and Poverty in India: The Cointegration and Causality Approach. Asian Soc. Sci. 6 (9), 114. doi:10.5539/ass.v6n9p114

Qamruzzaman, M., Jianguo, W., and Jianguo, W. (2018). Investigation of the Asymmetric Relationship between Financial Innovation, Banking Sector Development, and Economic Growth. Quantitative Finance Econ. 2 (4), 952–980. doi:10.3934/qfe.2018.4.952

Qamruzzaman, M., and Karim, S. (2020). Do Remittance and Financial Innovation Causes Stock Price through Financial Development: An Application of Nonlinear Framework.

Qamruzzaman, M. (2022). Nexus between Economic Policy Uncertainty and Institutional Quality: Evidence from India and Pakistan. Macroecon. Finance Emerg. Mark. Econ., 1–20. doi:10.1080/17520843.2022.2026035

Qamruzzaman, M. (2021). Nexus between Environmental Quality, Institutional Quality and Trade Openness through the Channel of FDI: An Application of Common Correlated Effects Estimation (CCEE), NARDL, and Asymmetry Causality Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 52475–52498. doi:10.1007/s11356-021-14269-8

Qamruzzaman, M., and Wei, J. (2019). Financial Innovation and Financial Inclusion Nexus in South Asian Countries: Evidence from Symmetric and Asymmetric Panel Investigation. Ijfs 7 (4), 61. doi:10.3390/ijfs7040061

Qamruzzaman, M., Wei, J., and Wei, J. (2019). Do financial Inclusion, Stock Market Development Attract Foreign Capital Flows in Developing Economy: a Panel Data Investigation. Quantitative Finance Econ. 3 (1), 88–108. doi:10.3934/qfe.2019.1.88

Rajan, R. G., and Zingales, L. (2003). The Great Reversals: the Politics of Financial Development in the Twentieth Century. J. financial Econ. 69 (1), 5–50. doi:10.1016/s0304-405x(03)00125-9

Rajan, R., and Zingales, L. (1998). Financial Development and Growth. Am. Econ. Rev. 88 (3), 559–586.

Ramasamy, B., and Yeung, M., The Determinants of Foreign Direct Investment in Services. 2010. 33(4): p. 573–596. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9701.2009.01256.x

Sachs, J. D. (2005). Investing in Development: A Practical Plan to Achieve the Millennium Development Goals. 1st Edn. CRC Press. doi:10.4324/9780429332937

Saidu, I., and Marafa, A. A. (2020). The Effect of Financial Sector Development on Poverty Reduction in Nigeria: An Empirical Investigation. Ijefi 10 (4), 9–17. doi:10.32479/ijefi.9532

Sanjaya, I. (2014). Financial Inclusion and Inclusive Growth as a Poverty Alleviation Strategy in Indonesia. Bogor, Indonesia: Bogor Agricultural University.

Sen, A. (1976). Poverty: An Ordinal Approach to Measurement. Econometrica 44, 219–231. doi:10.2307/1912718

Serneels, P., and Dercon, S. (2020). Aspirations, Poverty and Education: Evidence from India. J. Dev. Stud. doi:10.35489/bsg-rise-wp_2020/053

Serneels, P., and Dercon, S. (2021). Aspirations, Poverty, and Education. Evidence from India. J. Dev. Stud. 57 (1), 163–183. doi:10.1080/00220388.2020.1806242

Sharma, D. (2016). Nexus between Financial Inclusion and Economic Growth. Jfep 8 (1), 13–36. doi:10.1108/jfep-01-2015-0004

Shen, Y., and Li, S. (2022). Eliminating Poverty through Development: The Dynamic Evolution of Multidimensional Poverty in Rural China. Econ. Political Stud., 1–20. doi:10.1080/20954816.2022.2028992

Singh, P. K., and Chudasama, H. (2020). Evaluating Poverty Alleviation Strategies in a Developing Country. PLOS ONE 15 (1), e0227176. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0227176

Tambunan, T. (2015). Financial Inclusion, Financial Education, and Financial Regulation: A Story from Indonesia.

Thapa, S. B. (2013). Relationship between Education and Poverty in Nepal. Econ. J. Dev. Issues, 148–161.

Tilak, J. B. G. (2002). Education and Poverty. J. Hum. Dev. 3 (2), 191–207. doi:10.1080/14649880220147301

Tilak, J. B. G. (2007). Post-elementary Education, Poverty and Development in India. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 27 (4), 435–445. doi:10.1016/j.ijedudev.2006.09.018

Toda, H. Y., and Yamamoto, T. (1995). Statistical Inference in Vector Autoregressions with Possibly Integrated Processes. J. Econ. 66 (1-2), 225–250. doi:10.1016/0304-4076(94)01616-8

Westerlund, J. (2007). Testing for Error Correction in Panel Data. Oxf. Bull Econ Stats 69 (6), 709–748. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0084.2007.00477.x

World Bank (2021). World Development Indicators. cited 2017; Available from: http://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/world-development-indicators.

Yang, Y., Qamruzzaman, M., Rehman, M. Z., and Karim, S. (2021). Do Tourism and Institutional Quality Asymmetrically Effects on FDI Sustainability in BIMSTEC Countries: An Application of ARDL, CS-ARDL, NARDL, and Asymmetric Causality Test. Sustainability 13 (17), 9989. doi:10.3390/su13179989

Zahonogo, P. (2017). Financial Development and Poverty in Developing Countries: Evidence from Sub-saharan Africa. Int. J. Econ. Finance 9 (1), 211–220.

Zhuo, J., and Qamruzzaman, M. (2021). Do financial Development, FDI, and Globalization Intensify Environmental Degradation through the Channel of Energy Consumption: Evidence from Belt and Road Countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. doi:10.1007/s11356-021-15796-0

Zins, A., and Weill, L. (2016). The Determinants of Financial Inclusion in Africa. Rev. Dev. Finance 6 (1), 46–57. doi:10.1016/j.rdf.2016.05.001

Keywords: education, financial inclusion, poverty, GMM, system-GMM JEL classification: I32, G23

Citation: Shi Z and Qamruzzaman M (2022) Re-Visiting the Role of Education on Poverty Through the Channel of Financial Inclusion: Evidence From Lower-Income and Lower-Middle-Income Countries. Front. Environ. Sci. 10:873652. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2022.873652

Received: 11 February 2022; Accepted: 19 April 2022;

Published: 23 May 2022.

Edited by:

Cosimo Magazzino, Roma Tre University, ItalyReviewed by:

Irina Tulyakova, Saint Petersburg State University, RussiaTomas Kliestik, University of Žilina, Slovakia

Copyright © 2022 Shi and Qamruzzaman. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Md. Qamruzzaman, zaman_wut16@yahoo.com, orcid.org/0000-0002-0854-2600

Zheng Shi1

Zheng Shi1  Md. Qamruzzaman

Md. Qamruzzaman