- 1Department of Social Medicine and Health Management, Xiangya School of Public Health, Central South University, Changsha, China

- 2Hunan Provincial Key Laboratory of Clinical Epidemiology, Changsha, China

Background: In response to the potentially concurrent mental health crisis due to the COVID-19 outbreak, there have been ongoing mental health policies put in place in China. This review aims to systematically synthesize the implemented national-level mental health policies released by the Chinese government during the COVID-19 outbreak, and summarize the implementation of those mental health policies.

Methods: Six databases and two websites were systematically searched, including published studies and gray literature published between December 1, 2019 and October 29, 2020.

Results: A total of 40 studies were included. Among them, 19 were national-level policies on mental health released by the Chinese government, and 21 studies reported data on the implementation of those mental health policies. Mental health policies were issued for COVID-19 patients, suspected cases, medical staff, the general population, patients with mental illness, and mental institutions. In the early stage of the COVID-19 epidemic, attention was paid to psychological crisis intervention. In the later stage of the epidemic, the government focused mainly on psychological rehabilitation. During the COVID-19 outbreak, more than 500 psychiatrists from all over China were sent to Wuhan, about 625 hotlines were notified in 31 provinces, several online psychological consultation platforms were established, social software such as TikTok, Weibo, and WeChat were used for psychological education, and many books on mental health were published. Responding quickly, maximizing the use of resources, and emphasizing the importance of policy evaluation and implementation quality were characteristics of the mental health policies developed during the COVID-19 outbreak. Challenges facing China include a low rate of mental health service utilization, a lack of evaluation data on policy effects, and no existing national-level emergency response system and designated workforce to provide psychological crisis interventions during a national emergency or disaster.

Conclusions: This review suggests that China has responded quickly and comprehensively to a possible mental health crisis during the COVID-19 outbreak, appropriate mental health policies were released for different members of the population. As the epidemic situation continues to change, the focus of mental health policies has been adjusted accordingly. However, we should note that there has been a lack of separate policies for specific mental health issues during the COVID-19 outbreak.

Introduction

Over the past two decades, novel viruses have continued to emerge, the number of reported outbreaks of highly pathogenic or highly transmitted infectious diseases (such as SARS in 2003, H1N1 in 2009, MERS-CoV in 2012, and Ebola in 2014) has increased. At the end of 2019, a new type of infectious disease emerged, known as COVID-19 (1). As of November 10, 2020, over 49.7 million reported cases of COVID-19 and ~1.2 million deaths have been reported to the World Health Organization (WHO) (2). The outbreak of infectious diseases can spread rapidly, causing enormous losses to individual health, national economy, and social well-being (3).

The COVID-19 outbreak in China was shown to have a substantial negative impact on individuals' mental health, leading to clinical and sub-clinical disorders, such as acute stress disorder, depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and other mental health symptoms (4–7). In response to the potentially concurrent mental health crisis, there have been ongoing mental health policies implemented in China, which has important ramifications for mental health systems and the patients they serve.

A mental health policy is a set of ideas or plans that are used as a basis for making decisions in mental health, it is a government statement that clarifies the values, principles, and goals of mental health (8). A mental health policy can be implemented at multiple levels, for example in the forms of mental health plans, programs, strategies, and legislation. If formulated and implemented properly, a mental health policy can become an important and powerful tool for countries to improve mental health and reduce the burden of mental disorders (8). Although some studies were conducted in the early stages of the COVID-19 epidemic, summarizing the mental health efforts of the Chinese government (9–11), many questions remain unanswered. This scoping review aims to present mental health policy developments during the COVID-19 outbreak in China and search for the answers to three questions that may be critical to policy making for other countries: (i) in different populations, is the focus of mental health policies different? (ii) what are the focuses of mental health policies at different stages of the epidemic? (iii) what is the implementation status of these mental health policies? To explore these questions, this review aims to systematically synthesize the national-level mental health policies released by the Chinese government during the COVID-19 outbreak through published research and gray literature, and summarize the implementation status of these mental health policies.

Methods

A scoping review methodology (12, 13) was performed in this study according to the checklist of the PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) (14) (see Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Material) and a methodology framework described by Arksey et al. (12) consisting of seven stages. The stages of the methodology framework undertaken were: (1) identification of research objectives; (2) reviewing data sources and search strategies; (3) study selection; (4) data extraction; (5) quality assessment for the included studies; (6) collating, summarizing, and analyzing outcome evidence; and (7) describing implications for further research.

Research Objectives

• To identify the national-level mental health policies released by the Chinese government during the COVID-19 outbreak.

• To identify the focuses of mental health policies among different populations during the COVID-19 outbreak.

• To identify the focuses of mental health policies at different stages of the epidemic.

• To identify the implementation status of these mental health policies released by the Chinese government during the COVID-19 outbreak.

Data Sources and Search Strategies

A systematic search was conducted in six databases and two websites.

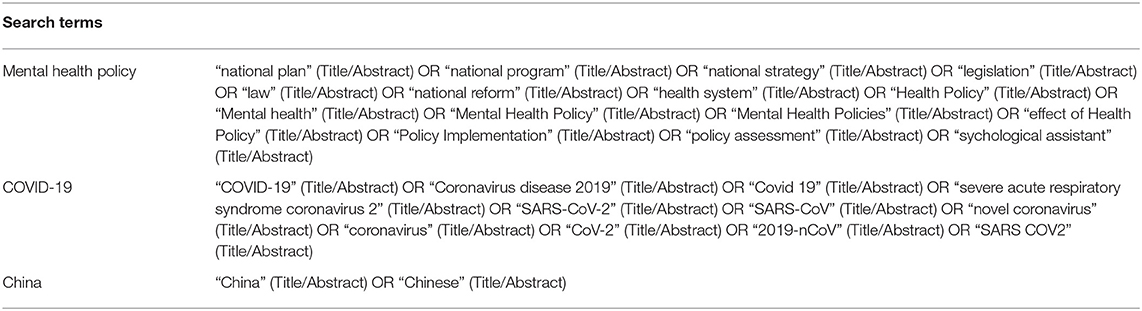

Specifically, three databases including Web of Science, Pubmed, and CNKI were searched for published research. We set a restriction on the publication date, only studies published between December 1, 2019 and October 29, 2020 were searched for. See Additional File 1 for the details. The following search terms were used: “mental health policy” (including health policy, mental health policy, national plan, national program, etc.); “COVID-19” (including COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Coronavirus disease 2019, etc.); China (including China and Chinese). See Table 1 and the Supplementary Material for a full search strategy.

Three databases including the National Science and Technology Library of China, the State Council Policy Document Database of China (http://www.gov.cn/index.htm), and the National Library of China and two websites including the Chinese Association for Mental Health (http://www.camh.org.cn/) and the Chinese Psychological Society (https://www.cpsbeijing.org/) were searched for gray literature. Keywords such as “policy,” “national plan,” “national program,” “COVID-19,” and “SARS-CoV-2” were combined with “mental health” in our search.

Selection Criteria

A national-level mental health policy is defined in this review as a mental health policy released by the State Council of China and its direct departments, aimed at improving the mental health of people who were influenced by COVID-19.

Inclusion criteria

We included studies that fulfilled all the following criteria:

a) For mental health policy documents issued by the government

• Participants: people who were influenced by COVID-19 and lived in China.

• Intervention: any national-level policy interventions delivered to people influenced by COVID-19 in China, aimed at improving their mental health.

b) For studies reporting data on the implementation of mental health policies

• Participants: people who were influenced by COVID-19 and lived in China.

• Intervention: any national-level policy interventions delivered to people influenced by COVID-19 in China, aimed at improving their mental health.

• Outcome: implementation status of mental policy interventions delivered to people influenced by COVID-19 in China, the quantity of mental health services provided in response to these mental health policies (such as how many psychiatrists were sent to provide psychological crisis intervention, how many hotlines were conducted, etc.).

• Study design: no restriction

Exclusion criteria

We excluded studies if:

• The study was not in English or Chinese.

• The study was a theoretical study, describing standards that mental health policies are expected to meet.

• The study was discussing the process of policy formulation.

• The report was a protocol.

Data Extraction

Identified records were first screened based on their titles and/or abstracts, and if they met the selection criteria, the full texts were obtained for further screening. The screening process was carried out independently by two authors (DQ and YLL). Data were extracted on date of publication, organizations, title of policy, and the main content of the policy independently by two reviewers (DQ and YLL).

Data Synthesis

The qualitative data of the included studies were combined in a synthesis (15, 16). The results were grouped, where possible, by two analytical themes: (i) policies to improve the mental health of people during the COVID-19 outbreak and (ii) the implementation of mental health policies developed during the COVID-19 outbreak. Consensus was reached on discrepancies in data extraction through discussion.

Quality Assessment

The methodological quality of the included studies was independently assessed by two reviewers (DQ and LL). Due to the varying study designs of included articles, checklists from The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) were utilized to assess content validity (17). See Supplementary Table 2 for details on the quality assessment.

Results

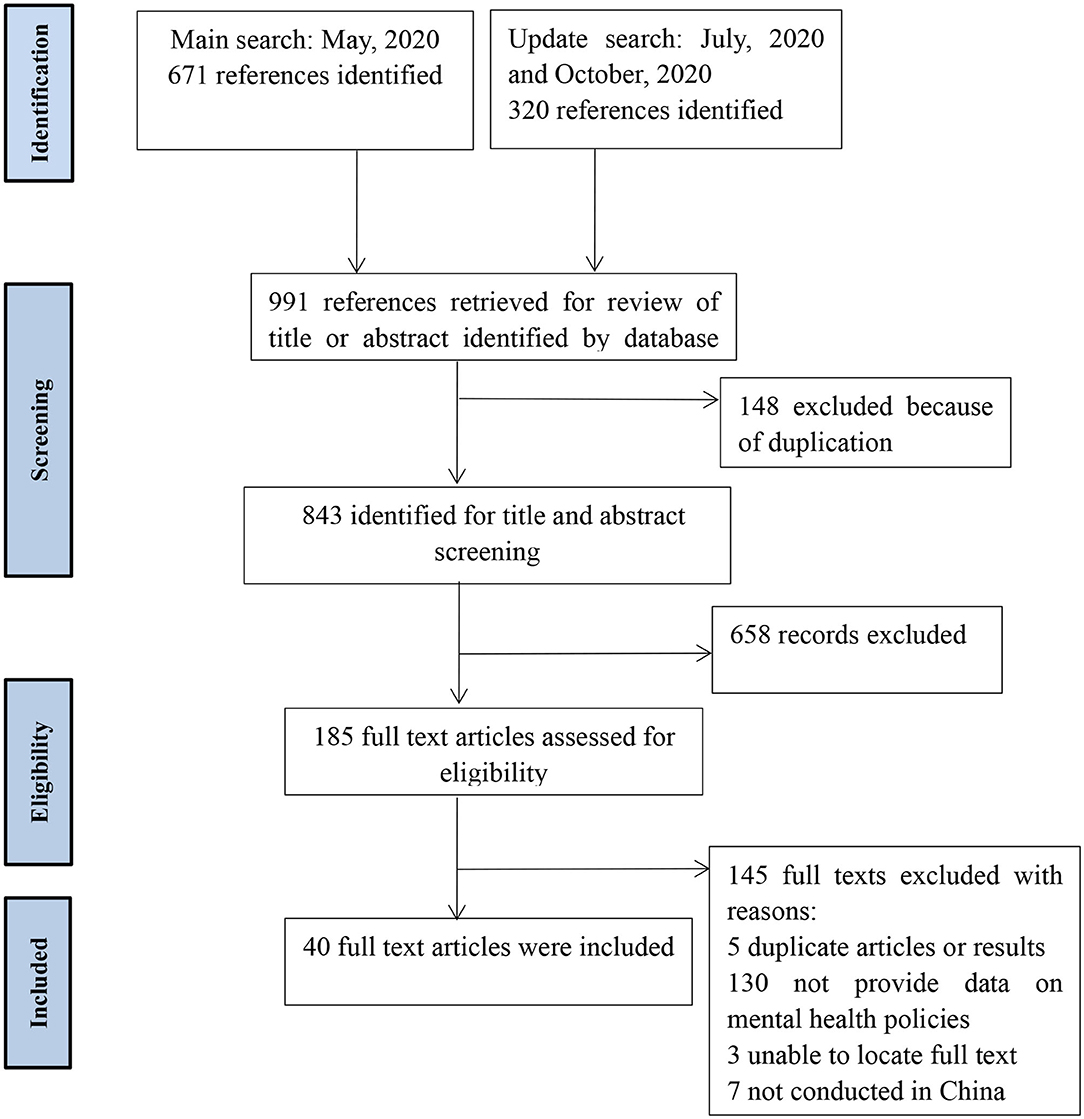

From the initially identified 991 records, 843 records were screened after duplicates were excluded. A total of 658 references were excluded based on the title or abstract, leaving 185 studies for further scrutiny. After screening the full texts, 145 studies were excluded. The 145 studies were excluded due to the following reasons: no data on mental health policies (n = 130); duplicate publications (n = 5); no full-text (n = 3); and not conducted in China (n = 7). Finally, 40 studies were included for analysis. See Figure 1 for the details.

Figure 1. Flow of studies through review (57).

Characteristics of the Included Studies

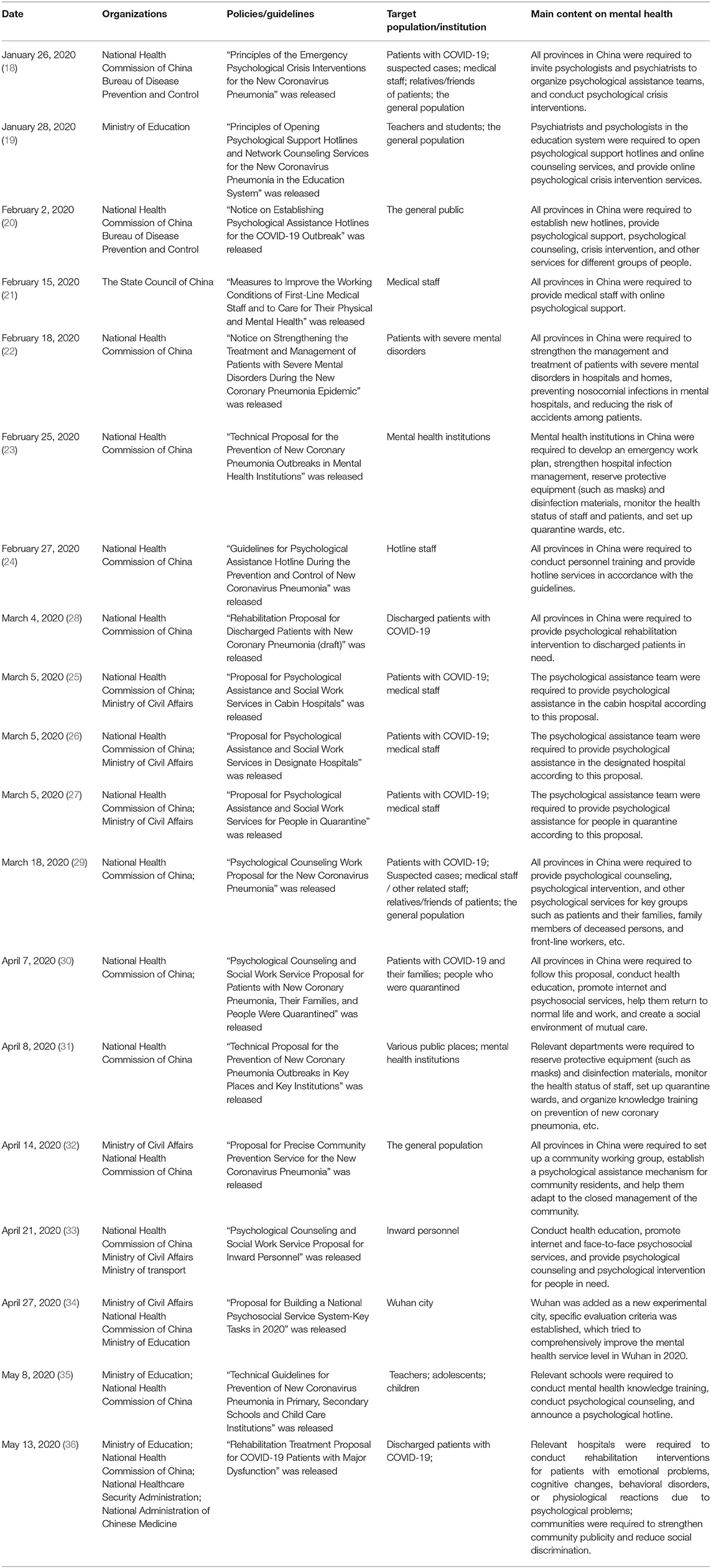

From January to July 2020, the Chinese government has issued a total of 19 national-level policies related to mental health (18–36). Among them, there were eight policies related to patients with COVID-19 or suspected cases (18, 25–30, 36), seven were related to medical staff (18, 21, 24–27, 29), five were related to the general population [18–20, 29, 32[, two were related to teachers and students (19, 35), one was related to patients with severe mental disorders (22), two were related to mental health institutions (23, 31) and one was related to inward personnel (33). Besides, 18 studies (9–11, 37–54) reported data on the implementation of mental health policies developed during the COVID-19 outbreak. Of the 21 studies, 17 were of sound methodological quality, while the remaining articles were reported to have indeterminate quality, see Supplementary Table 3 for the details.

Policies to Improve the Mental Health of People During the COVID-19 Outbreak

For patients with COVID-19 or suspected cases, the first guideline document was released on January 26, 2020. In this document (18), the National Health Commission of China suggested that all provinces in China invite psychologists and psychiatrists to organize psychological assistance teams and conduct psychological crisis interventions for patients in need. On March 5, three guideline documents for patients with COVID-19 or suspected cases were released by the Chinese government (25–27). Different psychological assistance programs were proposed for patients with different conditions. New psychological counseling work proposals were released on March 18 and April 7. Besides patients, these proposals paid more attention to the mental health of their family, friends, and colleagues (29, 30). Also, measures were taken to promote internet and psychosocial services, helping patients return to normal life. On March 4, the first version of the rehabilitation treatment proposal for discharged patients was released (28). All provinces in China were required to provide psychological rehabilitation intervention to discharged patients in need. The second version of the rehabilitation treatment proposal for COVID-19 patients was released on May 13, a more detailed psychological intervention plan was proposed for different types of mental health problems (36). Additionally, it was recommended that local governments organize social workers to conduct health education, eliminate community discrimination, and reduce patients' stigma.

For medical staff, the Chinese government proposed six related policies from January 26 to March 18. In January, the point of the policy was to provide emergency psychological crisis intervention for medical staff in need (18). In February, the list of online psychological assistance institutions for medical staff was released. The main target was to improve the protection measures of medical staff, improve their working environment, provide psychological assistance, and relieve their anxiety and stress (21, 24). Providing psychological education and skills training, organizing psychological support and emotional counseling services, and improving the self-help skills of medical staff were the main targets in March (25–27).

For the general population, the Chinese government released a total of six related policies from January 26 to April 14. Between January and March, the main targets of those policies were to provide internet/telephone-based emergency psychological crisis intervention or face-to-face psychological assistance for those people in need (18–20, 29). In April, the main targets changed to guiding people in medium-risk and high-risk areas to adapt to a closed life (32). For teachers and students, the Chinese government proposed a total of two related policies from January 28 to May 8. On January 28, the Ministry of Education required psychiatrists and psychologists in the education system to open psychological support hotlines and online counseling services, and provide online psychological crisis intervention services for teachers and students (19). In May, primary schools, secondary schools, and kindergartens in most areas reopened, the main targets changed to carrying out psychological education, psychological consultation, and creating psychological help hotlines for teachers and students (35). As the overseas epidemic become more serious, the Chinese government proposed measures against inward personnel in April, trying to provide psychological counseling and psychological intervention for inward personnel in need (33).

In order to prevent the spread of COVID-19 in mental health institutions and patients with severe mental disorders, the Chinese government proposed a total of three policies (22, 23, 31). Mental health institutions were suggested to strengthen hospital infection management, reserve protective equipment (such as masks) and disinfection materials, monitor the health status of staff and patients, and set up quarantine wards, etc. In addition, the proposal for “Building a National Psychosocial Service System-Key Tasks in 2020” was released (34). The government established specific evaluation criteria, added Wuhan as a new experimental city, and tried to comprehensively improve the mental health service level in Wuhan in a year. See Table 2 for the details.

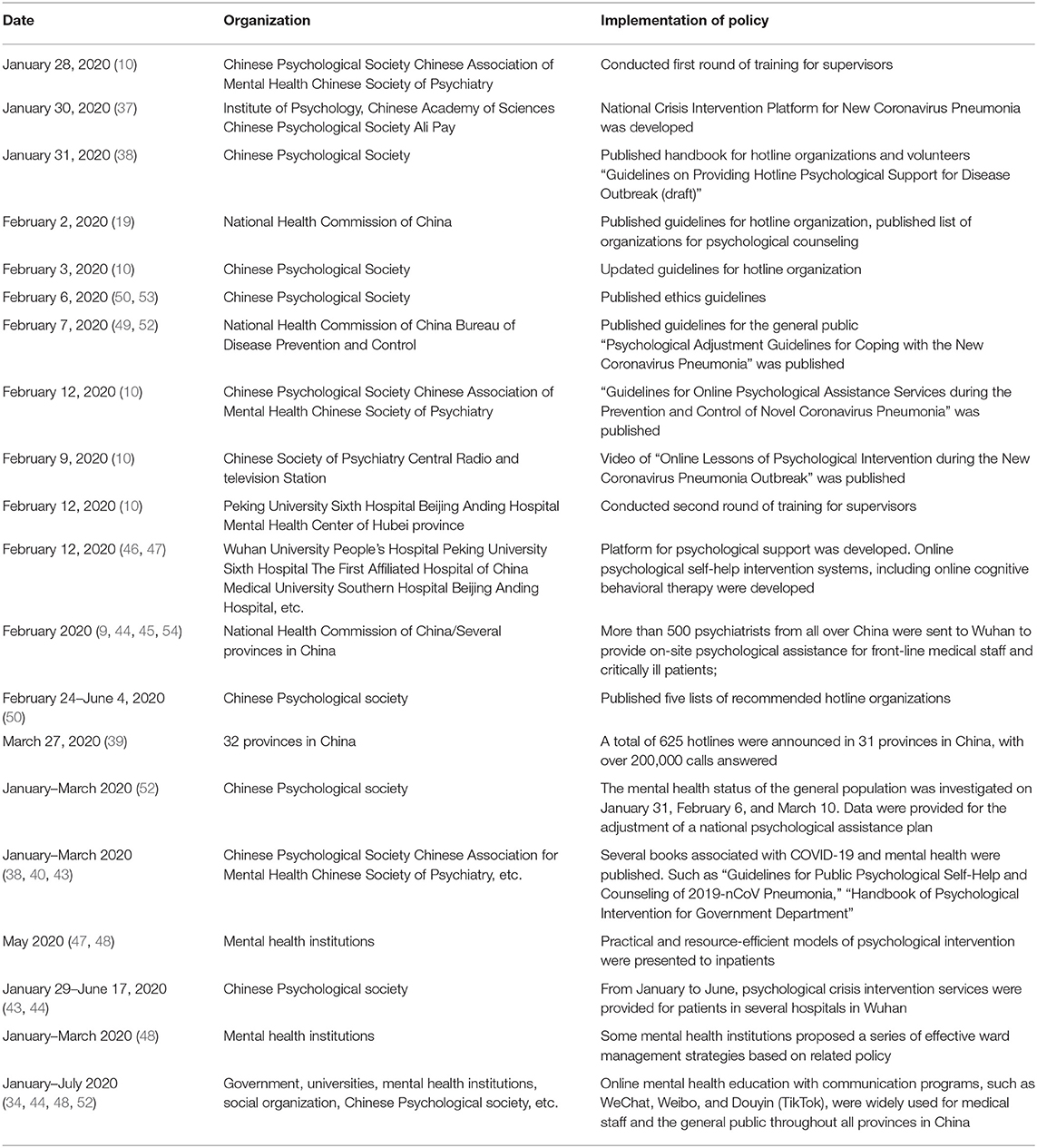

The Implementation of Mental Health Policies Developed During the COVID-19 Outbreak

In response to the first guideline document published on January 26, the Chinese Psychological Society and other psychological institutions organized the first round of personnel training on January 28 and released serval guidelines for hotline services between January 31 to February 6 (9, 20, 38, 50, 53). On February 7, the National Health Commission of China published a psychological adjustment guideline for the general public (49, 52). Between January and March, several books associated with COVID-19 and mental health were published (10, 40, 43). Such as “Guidelines for Public Psychological Self-Help of 2019-nCoV Pneumonia” and the “Handbook of Psychological Intervention for Government Departments, Enterprises, and Organizations.” Also, several platforms for psychological support were developed, those platforms developed online psychological self-help intervention systems, including interventions such as online cognitive behavioral therapy (41, 46, 47). Additionally, the Chinese Psychological Society published five lists of recommended hotline organizations, conducted three national surveys to investigate the mental health status of the general population, and provided references for the government to adjust its mental health policy in time (51).

At the end of February, more than 500 psychiatrists from all over China had been sent to Wuhan by several provinces to provide on-site psychological assistance for front-line medical staff and critically ill patients with COVID-19 (42, 45, 54). As of March 27, a total of 625 hotlines were notified in 31 provinces across China, with over 200,000 calls answered (39). A series of online mental health education programs on social media platforms, such as WeChat, Weibo, and Douyin (TikTok), have been developed and widely used for patients, medical staff, and the general public throughout all provinces in China (11, 43, 47). Besides, from January to June, the Chinese Psychological Society and other psychological institutions provided face-to-face psychological crisis intervention services for patients and medical staff in several hospitals in Wuhan according to the related policies (43, 44). Furthermore, some mental health institutions proposed a series of effective ward management strategies based on related policies and presented practical and resource-efficient models of psychological intervention for inpatients (48). See Table 3 for the details.

Discussion

Key Findings

Our review suggests that China has responded quickly and comprehensively to the possible mental health crisis among different populations during the COVID-19 outbreak. In response to the COVID-19 outbreak, there have been ongoing measures and concerted efforts in China, resources were used as much as possible to implement these mental health policies. In the early stages of the epidemic, the focus of these mental health policies was to mobilize various resources and provide psychological crisis intervention for people in need. In the later stage, the focus of these mental health policies was on psychological rehabilitation intervention. Besides, the importance of providing online psychological counseling and improving people's self-help ability has been emphasized throughout the epidemic period. Psychiatrists from all over China were sent to Wuhan by several provinces to provide on-site psychological assistance. Mental health hotlines were quickly established across China and provided patients, medical staff, and the general public with counseling and psychological services. The telephone-based and internet-based programs were widely used to deliver mental health care services, and social media platforms (e.g., TikTok, WeChat, and Weibo) were widely utilized to share strategies, guidelines, and education programs for managing potential mental health problems. In addition, governments, academic groups, and medical institutions also published many self-help handbooks on psychological interventions related to COVID-19.

Characteristics of Mental Health Policies During the COVID-19 Outbreak

Firstly, psychosocial interventions were organized very quickly to deal with the COVID-19 outbreak. On January 26, just 3 days after the lockdown implementation of Wuhan, the Chinese government published a guideline document for emergency psychological crisis interventions for the public (18). After this document was released, psychiatrists from all over China were immediately sent to Wuhan to provide psychological assistance, and several hotlines and internet-based platforms were developed for psychological counseling (10). However, some drawbacks of these policies should be noted. For example, who should deliver which type of intervention, for which group in need, and by which delivery mode were not specified in most policies (55). Also, we think there was a lack of separate policies for specific mental health issues during the COVID-19 outbreak. Such as PTSD, which is one of the most common mental health problems in a national emergency or disaster (56).

Another feature was the extensive use of mental health resources. Under the guidance of these mental health policies, cooperation between different institutions and organizations maximized the use of resources. Since January 24, 2020, some institutions had already launched a free crisis intervention hotline for the public (45). The government, academic societies, and hospitals quickly carried out cross-organizational cooperation, mobilized the resources they had, organized online training, organized academic conferences, and conducted telephone-based psychological interventions and internet-based psychological interventions for the public across China. Given that the fast transmission of the novel coronavirus between people may hinder traditional face-to-face psychological interventions and the widespread adoption of smartphones, online mental health services were heavily used in China. Massive use of online mental health services may maximize the beneficiaries from those programs, contributing to helping remove the barriers to accessing quality care for mental health.

Thirdly, the importance of implementation quality and outcome evaluation of those mental health interventions was emphasized. The Chinese government had emphasized in several guidelines that it was necessary to use qualified organizations and staff to provide psychological interventions, they also pointed out the importance of professional training (18, 24, 28, 31). Besides, the ethics of psychological intervention were highly valued in related guidelines (50). Also, the evaluation of the effectiveness of psychological interventions were emphasized (24), and the focus of psychological assistance was constantly being adjusted as the epidemic changed.

Challenges of Mental Health Policies During the COVID-19 Outbreak

It is said that China has long been faced with an extremely low rate of mental health service utilization (58, 59). To date, most of the attention has been focused on the provision of mental health services, with the utilization of these services to a large extent neglected. He et al. (58, 60) reported that only 3.70–5.58% of the general population actively sought out mental health services during the COVID-19 outbreak. After a large increase in mental health services, how to improve the utilization of services is also an issue that needs to be urgently considered.

Due to the relatively short duration of the outbreak, many mental health policies released during the outbreak of COVID-19 had been implemented for only a few weeks, the implementation data found in the current review were limited. Based on the included data, it seems that most of mental health policies released during the COVID-19 outbreak were implemented, but the process and quality of implementation is still unclear. Although the importance of implementation quality and outcome evaluation of those mental health interventions was emphasized, relative data have not yet been published. Nationwide surveys of psychological well-being during the COVID-19 outbreak were conducted (61, 62), but those surveys did not describe whether they used mental health services. Another question is that most mental health services were provided via telephone and the internet. Both the implementation quality and program effectiveness are difficult to guarantee (9, 58). Thus, we think the integration of assessment in structure, process, and outcomes of those mental health programs is needed in the forthcoming months. These recommendations may inform how other countries can overcome the shortage of mental health resources when facing the COVID-19 outbreak. Moreover, people with low socioeconomic status (SES) may not be able to take full advantage of digital technologies that online mental health services rely on (46, 58). What should be considered is whether the uneven development of online mental health services for this epidemic will widen the mental health gap in China.

Furthermore, China currently lacks a well-established mental healthcare system, and has no existing national-level emergency response system and designated workforce to provide psychological crisis interventions during a national emergency or disaster (55). The shortage of professional human resources on mental health is also a problem. Over the past decade, the number of psychiatrists in China has increased (63). However, the amount of mental health professionals still cannot meet the needs of psychosocial intervention during this kind of large-scale epidemic (42). System defects and lack of personnel may have affected the implementation of mental health policies during the COVID-19 outbreak (64). In order to better respond to infectious disease outbreaks and ensure the effectiveness of mental health policies, it is important to address these issues in the future.

Limitations

At first, the implementation data found in the current review were limited. It seems that most of the mental health policies released during the COVID-19 outbreak were implemented, but the process and quality of implementation is still unclear, which needs further exploration. Secondly, in order to presented as much data related to policy implementation as possible, we have included data from some comments and letters to the editor, which may not have been peer-reviewed. Another possible limitation is that this review is based on implemented mental health policies at the national level. Since all provinces in China are basically carrying out relevant work under the guidance of national-level mental health policies, we did not consider local-level mental health policies, there may be bias in the representativeness of the results.

Implications for Future Research

Firstly, we think the long-term outcomes and implementation quality of these mental health interventions need further evaluation in future studies. Secondly, it is necessary to evaluate the impact of those known problems (such as low utilization of mental health services, with no existing national-level emergency response system and designated workforce) on the implementation of these mental health policies released during the outbreak of COVID-19. Besides, there was a lack of separate policies for specific mental health issues during the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Future research is needed to explore the necessity of making separate policies for some common mental health problems (such as PTSD) in a national emergency or disaster.

Conclusions

This review suggests that China has responded quickly and comprehensively to the possible mental health crisis during the COVID-19 outbreak, appropriate mental health policies were released for different populations. As the epidemic situation continued to change, the focus of mental health policies was adjusted accordingly. However, we should note that there was a lack of separate policies for specific mental health issues during the COVID-19 outbreak. Such as PTSD, which is one of the most common mental health problems in a national emergency or disaster. In addition, the combination of telemedicine and face-to-face mental health services should be considered in middle-income and low-income countries, which may help remove barriers to accessing quality mental health care. Lastly, we believe this is a critical time to recognize these extraordinary advances in policy making, as it provides an unprecedented opportunity to evaluate the effects of mental health policies that China may adopt in the post-COVID-19 era.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions generated in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

SX and DQ contributed to the design of the study. JH and FO searched through the databases. DQ and YL screened the text. DQ and LL extracted and analyzed the data. DQ wrote the first draft of the manuscript with input from SX. All the authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (Grant No: 2016YFC0900802).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; SARS, severe acute respiratory syndrome; MERS-CoV, Middle East respiratory syndrome; Ebola, Ebola virus disease; WHO, World Health Organization; H1N1, 2009 influenza A(H1N1); PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; SES, socioeconomic status.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.588137/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Houlihan CF, Whitworth JA. Outbreak science: recent progress in the detection and response to outbreaks of infectious diseases. Clin Med. (2019) 19:140–4. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.19-2-140

2. Organization WH. Weekly Epidemiological Update−10 November 2020. (2020) Available online at: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports/ (accessed October 12, 2020).

3. Steele L, Orefuwa E, Dickmann P. Drivers of earlier infectious disease outbreak detection: a systematic literature review. Int J Infect Dis. (2016) 53:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2016.10.005

4. Chen S, Li F, Lin C, Han Y, Nie X, Portnoy RN, et al. Challenges and recommendations for mental health providers during the COVID-19 pandemic: the experience of China's First University-based mental health team. Glob Health. (2020) 16:59. doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00591-2

5. Zhang WR, Wang K, Yin L, Zhao WF, Xue Q, Peng M, et al. Mental health and psychosocial problems of medical health workers during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Psychother Psychosom. (2020) 89:242–50. doi: 10.1159/000507639

6. Liu N, Zhang F, Wei C, Jia Y, Shang Z, Sun L, et al. Prevalence and predictors of PTSS during COVID-19 outbreak in China hardest-hit areas: gender differences matter. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 287:112921. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112921

7. Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, McIntyre RS, et al. A longitudinal study on the mental health of general population during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Brain Behav Immun. (2020) 87:40–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.028

8. Zhou W, Yu Y, Yang M, Chen L, Xiao S. Policy development and challenges of global mental health: a systematic review of published studies of national-level mental health policies. BMC Psychiatry. (2018) 18:138. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1711-1

9. Miu A, Cao H, Zhang B, Zhang H. Review of mental health response to COVID-19, China. Emerg Infect Dis. (2020) 26:2482–4. doi: 10.3201/eid2610.201113

10. Li W, Yang Y, Liu ZH, Zhao YJ, Zhang Q, Zhang L, et al. Progression of mental health services during the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Int J Biol Sci. (2020) 16:1732–8. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.45120

11. Liu S, Yang L, Zhang C, Xiang YT, Liu Z, Hu S, et al. Online mental health services in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry. (2020) 7:e17–8. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30077-8

12. Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. (2005) 8:19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616

13. Armstrong R, Hall BJ, Doyle J, Waters E. ‘Scoping the scope’ of a cochrane review. J Public Health (Oxf). (2011) 33:147–50. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdr015

14. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. (2018) 169:467–73. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850

15. Suri H, Clarke D. Advancements in research synthesis methods: from a methodologically inclusive perspective. Rev Educ Res. (2009) 79:395–430. doi: 10.3102/0034654308326349

16. Dixon-Woods M, Agarwal S, Jones D, Young B, Sutton A. Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: a review of possible methods. J Health Serv Res Policy. (2005) 10:45–53. doi: 10.1177/135581960501000110

17. Braithwaite J, Zurynski Y, Ludlow K, Holt J, Augustsson H, Campbell M. Towards sustainable healthcare system performance in the 21st century in high-income countries: a protocol for a systematic review of the grey literature. BMJ Open. (2019) 9:e025892. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025892

18. China NHCo. Principles of the Emergency Psychological Crisis Interventions for the New Coronavirus Pneumonia. (2020). Available online at: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2020-01/27/content_5472433.htm (accessed July 18, 2020).

19. Education Mo. Principles of Opening Psychological Support Hotlines and Network Counseling Services for the New Coronavirus Pneumonia in the Education System. (2020). Available online at: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2020-01/28/content_5472681.htm (accessed July 18, 2020).

20. China NHCo. Notices on Establishing Psychological Assistance Hotlines for the COVID-19 Outbreak. (2020). Available online at: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2020-02/02/content_5473937.htm (accessed July 18, 2020).

21. China TSCo. Notice on the Implementation of Several Measures to Improve the Working Conditions of First-Line Medical Staff and to Care for the Physical and Mental Health of Medical Staff. (2020). Available online at: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/zhengcwj/202002/85896fabe90747cba8b79beb4c57f202.shtml (accessed July 18, 2020).

22. China NHCo. Notice on Strengthening the Treatment and Management of Patients with Severe Mental Disorders During the New Coronary Pneumonia Epidemic. (2020). Available online at: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/zhengcwj/202002/f315a6bb2955474c8ca0b33b0c356a32.shtml (accessed July 18, 2020).

23. China NHCo. Technical Proposal for the Prevention of New Coronary Pneumonia Outbreaks in Mental Health Institutions. (2020). Available online at: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2020-02/25/content_5483024.htm (accessed July 18, 2020).

24. China NHCo. Guidelines for Psychological Assistance Hotline During the Prevention and Control of New Coronavirus Pneumonia (in Chinese). (2020). Available online at: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2020-02/27/content_5484047.htm (accessed July 18, 2020).

25. China NHCo, Affairs MoC. Proposal for Psychological Assistance and Social Work Services in Cabin Hospitals (in Chinese). (2020). Available online at: http://www.mca.gov.cn/article/xw/tzgg/202003/20200300025367.shtml (accessed July 18, 2020).

26. China NHCo, Affairs MoC. Proposal for Psychological Assistance and Social Work Services in Designate Hospitals (in Chinese). (2020). Available online at: http://www.mca.gov.cn/article/xw/tzgg/202003/20200300025367.shtml (accessed July 18, 2020).

27. China NHCo, Affairs MoC. Proposal for Psychological Assistance and Social Work Services for People in Quarantine (in Chinese). (2020). Available online at: http://www.mca.gov.cn/article/xw/tzgg/202003/20200300025367.shtml (accessed July 18, 2020).

28. China NHCo. Rehabilitation Proposal for Discharged Patients with New Coronary Pneumonia (Draft). (2020). Available online at: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2020-03/05/content_5487160.htm (accessed July 18, 2020).

29. China NHCo. Psychological Counseling Work Proposal for the New Coronavirus Pneumonia (in Chinese). (2020). Available online at: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2020-03/19/content_5493051.htm (accessed July 18, 2020).

30. China NHCo. Psychological Counseling and Social Work Service Proposal for Patients With New Coronary Pneumonia, their Families and People Were Quarantined (in Chinese). (2020). Available online at: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2020-04/08/content_5500131.htm (accessed July 18, 2020).

31. China NHCo. Technical Proposal for the Prevention of New Coronary Pneumonia Outbreaks in Key Places and Key Institutions (in Chinese). (2020). Available online at: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2020-04/09/content_5500689.htm (accessed July 18, 2020).

32. Affairs MoC, China NHCo. Proposal for Precise Community Prevention Service for the New Coronavirus Pneumonia (in Chinese). (2020). Available online at: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2020-04/16/content_5503261.htm (accessed July 18, 2020).

33. China NHCo, Affairs MoC, Transport Mo. Psychological Counseling and Social Work Service Proposal for Inward Personnel (in Chinese). (2020). Available online at: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/jkj/s5888/202004/2661b96444524b02b9f88fddb3d695f6.shtml (accessed July 18, 2020).

34. Affairs MoC, China NHCo, Education Mo. Proposal for Building a National Psychosocial Service System–Key Tasks in 2020 (in Chinese). (2020). Available online at: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/jkj/s5888/202004/3009df2cf619434899575cce6ae2af77.shtml (accessed July 18, 2020).

35. Education Mo, China NHCo. Technical Guidelines for Prevention of New Coronavirus Pneumonia in Primary and Secondary Schools and Child Care Institutions (in Chinese). (2020).

36. Education Mo, China NHCo, Administration NHS, Medicine NAoC. Rehabilitation Treatment Proposal for COVID-19 Patients with Major Dysfunction (in Chinese). (2020) Available online at: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/s7653pd/202005/b15d59b5228341129cc8c5126f663b10.shtml (accessed July 18, 2020).

37. Society CP. Psychological Assistance and Crisis Intervention in the Fight Against COVID-19 (in Chinese). (2020). Available online at: https://www.cpsbeijing.org/cms/show.action?code=publish_402880766305a05d016305ffc2710078&siteid=100000&newsid=eb5ea1131e064055972be41e296a0f3d&channelid=0000000036 (accessed July 20, 2020).

38. Society CP. Guidelines on Providing Hotline Psychological Support for Disease Outbreak (Draft). (2020). Available online at: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s?__biz=MzA3NzcyMDQ5MQ%3D%3D&mid=2650156017&idx=1&sn=38485d9d760ee1612dc2cd7cfb1eaf50&scene=45#wechat_redirect (accessed July 20, 2020)

39. Wang J, Wei H, Zhou L. Hotline services in China during COVID-19 pandemic. J Affec Disord. (2020) 275:125–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.030

40. Zhou J, Liu L, Xue P, Yang X, Tang X. Mental health response to the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Am J Psychiatry. (2020) 177:574–5. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20030304

41. Zhang XB, Gui YH, Xu X, Zhu DQ, Zhai YH, Ge XL, et al. Response to children's physical and mental needs during the COVID-19 outbreak. World J Pediatr. (2020) 16:278–9. doi: 10.1007/s12519-020-00365-1

42. Yang J, Tong J, Meng F, Feng Q, Ma H, Shi C, et al. Characteristics and challenges of psychological first aid in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Brain Behav Immun. (2020) 87:113–4. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.075

43. Wang Y, Zhao X, Feng Q, Liu L, Yao Y, Shi J. Psychological assistance during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in China. J Health Psychol. (2020) 25:733–7. doi: 10.1177/1359105320919177

44. Kang L, Li Y, Hu S, Chen M, Yang C, Yang BX, et al. The mental health of medical workers in Wuhan, China dealing with the 2019 novel coronavirus. Lancet Psychiatry. (2020) 7:e14. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30047-X

45. Kang C, Tong J, Meng F, Feng Q, Ma H, Shi C, et al. The role of mental health services during the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Asian J Psychiatry. (2020) 52:102176. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102176

46. Hu N, Pan S, Sun J, Wang Z, Mao H. Mental health treatment online during the COVID-19 outbreak. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2020) 270:783–4. doi: 10.1007/s00406-020-01129-8

47. Cui Y, Li Y, Zheng Y, Chinese Society of C, Adolescent P. Mental health services for children in China during the COVID-19 pandemic: results of an expert-based national survey among child and adolescent psychiatric hospitals. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2020) 29:743–8. doi: 10.1007/s00787-020-01548-x

48. Chen J, Xiong M, He Z, Shi W, Yue Y, He M. The enclosed ward management strategies in psychiatric hospitals during COVID-19 outbreak. Global Health. (2020) 16:53. doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00586-z

49. China NHCo. Psychological Adjustment Guidelines for Coping with the New Coronavirus Pneumonia (in Chinese). (2020). Available online at: http://www.gov.cn/fuwu/2020-02/08/content_5476190.htm (accessed July 20, 2020)

50. Society CP. Ethics Guidelines for Hotlines (Draft). (2020). Available online at: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/iG6eeV1-vAVfjf36SbdMLA (accessed July 20, 2020).

51. Society CP. Mental Health of the General Population During the COVID-19 Outbreak (The Third Round of Investigation). (2020). Available online at: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/YKLqbBpUMqO_ZPL_ApMYsg (accessed July 20, 2020)

52. Song M. Psychological stress responses to COVID-19 and adaptive strategies in China. World Dev. (2020) 136:105107. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105107

53. Rui Z, Jing W, Xue Z, Jing-xuan W, Lan P, Lei Z. Discussion on the working mode of COVID-19 public welfare hotline group under epidemic situation. Xinli Yuekan. (2020) 17:152–3. doi: 10.19738/j.cnki.psy.2020.17.062

54. Ju Y, Zhang Y, Wang X, Li W, Ng RMK, Li L. China's mental health support in response to COVID-19: progression, challenges and reflection. Global Health. (2020) 16:102. doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00634-8

55. Dong L, Bouey J. Public mental health crisis during COVID-19 pandemic, China. Emerg Infect Dis. (2020) 26:1616–8. doi: 10.3201/eid2607.200407

56. Xiao S, Luo D, Xiao Y. Survivors of COVID-19 are at high risk of posttraumatic stress disorder. Glob Health Res Policy. (2020) 5:29. doi: 10.1186/s41256-020-00155-2

57. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. (2009) 151:264–9. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

58. Yao H, Chen JH, Xu YF. Rethinking online mental health services in China during the COVID-19 epidemic. Asian J Psychiatry. (2020) 50:102015. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102015

59. Shi JW, Tang L, Jing LM, Geng JS, Liu R, Luo L, et al. Disparities in mental health care utilization among inpatients in various types of health institutions: a cross-sectional study based on EHR data in Shanghai, China. BMC Public Health. (2019) 19:1203–12. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7343-7

60. He L. A study on the characteristics of psychological-aid receiver in the period of covid-19. J Yibin Med Coll. (2020) 20:1–7. doi: 10.19504/j.cnki.issn1671-5365.2020.04.002

61. Gao J, Zheng P, Jia Y, Chen H, Mao Y, Chen S, et al. Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS ONE. (2020) 15:e0231924. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231924

62. Qiu JY, Shen B, Zhao M, Wang Z, Xie B, Xu YF. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. Gen Psychiatry. (2020) 33:e100213. doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100213

63. Shi C, Ma N, Wang L, Yi Ll, Wang X, Zhang W, et al. Study of the mental health resources in China. Chin J Health Policy. (2019) 12:51–7. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-2982.2019.02.008

Keywords: policy implementation, China, mental health policy, COVID-19, scoping review

Citation: Qiu D, Li Y, Li L, He J, Ouyang F and Xiao S (2020) Policies to Improve the Mental Health of People Influenced by COVID-19 in China: A Scoping Review. Front. Psychiatry 11:588137. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.588137

Received: 28 July 2020; Accepted: 17 November 2020;

Published: 11 December 2020.

Edited by:

Manasi Kumar, University of Nairobi, KenyaReviewed by:

Richa Tripathi, All India Institute of Medical Sciences Gorakhpur, IndiaRahul Shidhaye, Pravara Institute of Medical Sciences, India

Copyright © 2020 Qiu, Li, Li, He, Ouyang and Xiao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shuiyuan Xiao, xiaosy@csu.edu.cn

Dan Qiu

Dan Qiu Yilu Li1

Yilu Li1 Shuiyuan Xiao

Shuiyuan Xiao